“Last time I was kissed in a garden it turned out rather awful.”

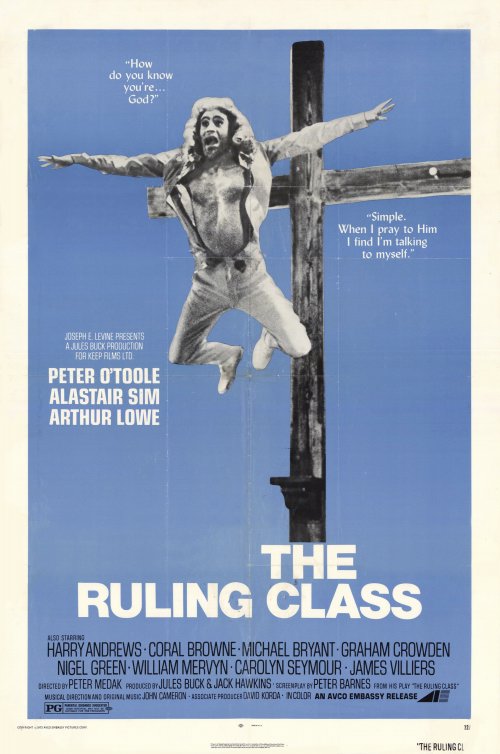

Those who find Monty Python’s The Life of Brian too offensive to stomach need not even attempt The Ruling Class. Based on a stage play by the same name, the film tells the story of Jack, the 14th Earl of Gurney, who believes himself to be the God of the New Testament, because, among other reasons, he finds that when he prays he is simply talking to himself. The character of Jack is brilliantly portrayed by Peter O’Toole, who stands head and shoulders above the rest of the cast for his sheer level of commitment to the absurd project and commands the audience’s attention every moment he is on screen. Although the gallows humor of its bizarre opening is immediately arresting, the film eventually meanders into less comedic waters, and it stumbles its way to an unsure conclusion marked by violence and hallucination. But it’s two and a half hours long and held my interest, or at least my curiousity, so it can’t be that bad, right?

It’s considered a cult classic today, and rightfully so—it’s profane, eclectic, and irreverent; the main character morphs from Jesus Christ into Jack the Ripper, sleeps upright on a cross, rides a tricycle around his honeymoon suite and routinely breaks out into song and dance (albeit infrequently enough that it’s still surprising every time he does). Even as Hollywood moved into new territory in the post-Hays code era, The Ruling Class snuck onto the British scene as one of those zany films that almost defies description because it’s so unlike any popular analog, producing head scratches and confused laughter with its unorthodox and frankly insane story.

Like every prophet I saw visions, I heard voices, I ran. The voices of Saint Frances, Socrates, General Gordon, and Timothy Leary, they all told me I was God. It was Sunday, August the 5th, at 3:32.

It’s almost incomprehensible as a narrative film; or at least, impossible to take seriously as one. The characters, almost without fail, are written without sufficient motivations. About the only thing we can understand from the hilariously macabre opening scene—in which Jack’s father (Harry Andrews) dons a tutu and a military tunic then accidentally hangs himself during some kind of sexual ritual—is that the rest of the family is faced with a predicament. As Jack is the only legitimate heir to his father’s earldom, they determine to marry Jack off, produce a new heir, and then have him committed to a rubber room by the Master of Lunacy. The plan almost fizzles before it begins, as Jack claims to already be married, though it is quickly discovered that he believes himself joined in holy matrimony to a character from an Alexander Dumas novel.

Once the plan is enacted, however, it backfires when Grace (Carolyn Seymour)—Jack’s uncle’s mistress, pretending to be Jack’s fictitious wife—actually falls in love with him. Upon meeting, the duo strut around on the lawn mimicking birds, pecking and chirping at one another. Jack’s uncle, a Bishop of the Church of England, reluctantly agrees to perform the wedding ceremony. Stammering his way through lines he’s said hundreds of times, he finally asks Jack to say his wedding vows. “Wilt thou, wilt thou take this woman to thy wedded wife, to live together i-i-in holy wedlock under God’s ordinance? W- W-Wilt thou love her?” “From the bottom of my soul to the tip of my penis,” Jack replies. “Like the sun in its brightness, the moon in its glory, no breeze stirs that doesn’t bear my love.”

Refusing to go by his real name—preferring to be called “J.C.” or any of the “nine billion names that people use to refer to God”—Jack ignores unfortunate facts by putting them into his “galvanized pressure cooker.” He endures several rounds of therapy but still comes out of it believing that he is God, a topic that O’Toole rips through in many rapidfire monologues launched into at the slightest provocation, or even as he hangs alone on his cross that he sleeps upon.

My heart rises with the sun. I’m purged of doubts and negative innuendos. Today I want to bless everything. Bless the crawfish with its scuttling walk. Bless the trout, pilchard and periwinkle. Bless Ted Smoothey of 22 East Hackney Road. Bless the mealy redpoll, the black-gloved wallaby and W.C. Fields, who is dead but lives on. Bless the snotty-nosed giraffe. Bless the buffalo. Bless the Society of Women Engineers. Bless the pygmy hippy. Bless the mighty cockroach.

As Grace is giving birth to Jack’s heir, the psychotherapist arranges an encounter with another patient, a man who also believes himself to be Jesus Christ and refers to himself as ‘The High Voltage Messiah.’ Affected as he is by paranoid schizophrenia, Jack becomes convinced that the man is actually channeling electricity through his fingers, and imagines himself being body slammed by a gorilla in a top hat, awakening from the trauma seemingly free from delusion. “I am Jack, I am Jack,” he mutters again and again. But not Jack the Earl—of course not. Jack the Ripper. And still God, too—the God of the Old Testament now. “Not the God of love, but God Almighty. I massacred the Amalekites and the Seven Nations of Canaan. I hacked Agag to pieces and blasted the barren fig tree, for the day of vengeance is in my heart.”

At this point, the film loses quite a bit of its steam. The laughter dies out, and instead the film becomes a cruel murder mystery, with the coldhearted Jack the Ripper at its center. O’Toole is as terrifying as Jack the Ripper as he was endearing as the delusional J.C. but the second half just doesn’t have the same irreverent charm of the oddball beginning. Put another way, the section of the film in which O’Toole plays the deluded messiah finds very few corollaries in cinema, and so can be viewed for its unique contribution to the medium; the second half has plenty of comps that are all much better than it. Anyway, as Jack slices his way through decadent socialites and loose women his psychiatrist finds nothing wrong with his new demeanor. Unhinged sadism, it turns out, is socially acceptable to the ruling class.

As entertaining as O’Toole is in the role—to be clear, I will likely never forget watching this film thanks to his mesmerizing performance—it is ultimately an overpowering bright spot. Indeed, it’s the entire reason to see the film. There just aren’t that many movies that cross ragtime musical with horrorshow with Jesus Christ with psychotherapy with social satire with yelling the f-word at a rabbit, and O’Toole is utterly committed to it all. It’s very unsettling to watch and it’s not the kind of thing I’d put on any old day of the week, but it’s certainly memorable and quotable and I understand why it has cult appeal.