“Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out.”

There were precisely three things that I liked about Doom, and the only one that isn’t merely a gimmicky Easter egg does not occur until there are only like twenty minutes left in the film. For the rest of its duration, Andrzej Bartkowiak’s video game adaptation falls flat on its face. It’s uninspired, cheap, hackneyed, and boring, and has none of the joy of the original game upon which it is based. I kind of figured that a game that is so delectable precisely because it doesn’t cheapen itself with a bland story would be tough to translate to the screen, but I thought they could have come up with something a little bit better than this. The game at least has atmosphere and style. The film doesn’t even get those right.

The first egg to catch my eye was the introduction, which replaces the usual Universal globe logo with the planet of Mars. That’s cool, but really meaningless. The second is that the head research scientist on Mars is named Dr. Carmack (Robert Russell), a nod to John Carmack, the genius mind that created the game engines upon which Doom and many other games were built, ushered in many innovative game design techniques, founded an aerospace startup, and worked on virtual reality and artificial general intelligence. The man is a true original who deserves all the praise he gets. But giving his name to a character in a movie based on a game he made does not make that movie good. It shouldn’t be one of the only things that piques my interest.

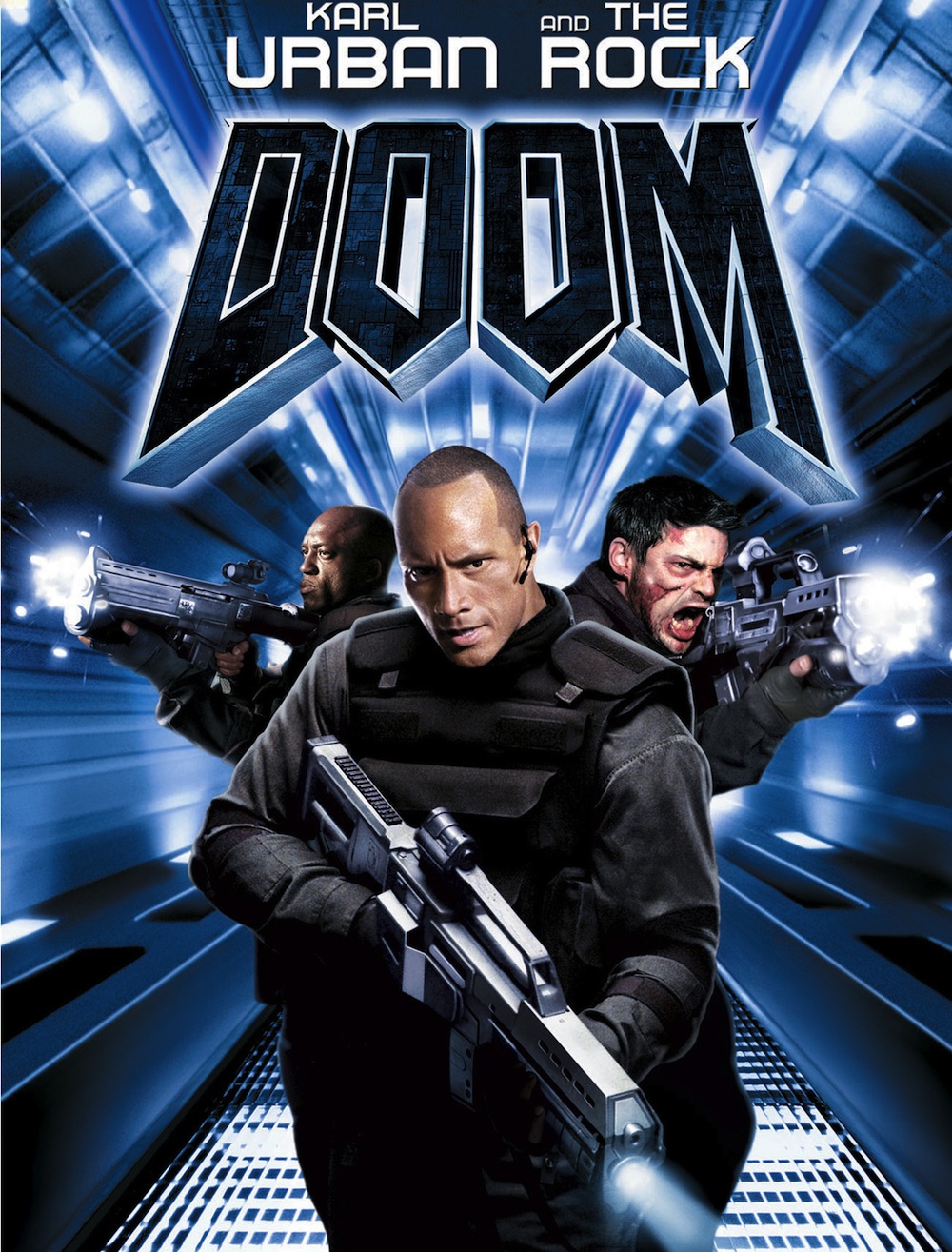

The movie is about a group of marines, led by Sarge (The Rock), that responds to a security breach at a research facility on Mars, where some creepy crawlies are terrorizing some researchers in a lab. There’s a bit of exposition about some anomalous portal found in the American desert that transports them there via a floating ball of CGI snot, which is required so that this can be a swift response rather than taking several months of space travel. Once on the red planet we meet Samantha (Rosamund Pike), who happens to be the sister of space marine Reaper (Karl Urban), Sarge’s second-in-command. There’s some scientific sounding mumbo jumbo that attempts to describe the mostly unseen creatures that are wreaking havoc on the station—something about extra chromosomes and differing reactions based on unmapped DNA.

The Rock eventually grew into his persona and has turned in some decently charismatic performances that cash in on his tough-guy act and allow him to flex his comedic side a little bit. But in 2005 he was still a pro-wrestler-turned-actor who was taking himself way too seriously for such a cheesy film. I regret to say that his performance is the best of the lot. Urban is given a decent amount of screentime but his lines were written by hacks so he can’t do much. Pike is basically there to look pretty and scream when someone near her is about to be slaughtered. The rest of the cast might as well have stopwatches over their heads that count down how long we have to wait for them to die.

We soon find out that these monsters can zombify humans. Of course, there’s no time for any real analysis of the situation. These things need destroyed. We get lots of shadowy corridors, shouted curses, and gunshots from very large weapons. In contrast with the colorful game, the movie version is very dark and visually uninteresting, with much of the budget seemingly tied up in only a few shots. The creatures are often veiled in shadows, which is lame, because it actually looks like the practical effects team did a pretty decent job. I’m not sure what else ate up their $60 million budget, because Urban, The Rock, and Pike were not yet big stars. The sets seem to be an afterthought, and the CGI that replaces Dexter Fletcher’s legs with a chassis and wheels and places transparent “nano walls” in doorways looks like it was done in an afternoon.

The only redeeming element of the film—and one that I’m not sure if I actually like or if I only appreciate it for its novelty—is a late section in which the camera morphs with Reaper’s point of view, and we sight down the barrel of his gun with him as he plows through a legion of man-eating creatures. It feels very much akin to an arcade shooting game, one of those ancient cabinet-style ones with brightly colored plastic guns attached via cord to the machine. You don’t control your movements, only where and when your shots are fired. It’s exactly like that, visually, and even if it’s not actually good, it’s at least bold. But it only accounts for about 5% of the film, and it’s more of a novelty thing to hail the gamer crowd (which should make up the entirety of the remaining audience for this film) than something indicative of quality.

The touchstones that the creators of Doom were tapping for inspiration are obvious—Alien, with it’s parasites burrowing into human hosts; The Thing and its gross-out body horror. But the lessons taken from those films seem to be only superficially gleaned. As a film, Doom is horrid. Even those who genuinely love big, dumb action and bloody horror should be able to point out plenty of things that are plainly done wrong. Video game adaptations are almost always terrible—though I have a weird fascination with the saga of Uwe Boll—and Doom only reinforces that stereotype.