“Sometimes awful things have their own kind of beauty.”

Considering that prior to sitting in the director’s chair for the first time, Tom Ford had already put in a few decades as a luxury fashion designer (a field I will not even pretend to understand, because then I’d have to try to explain why khakis and a polo constitute my idea of “dressing up”), it’s really no surprise that A Single Man is pretty to look at. It’s also not really a surprise that I don’t love it. I think, in some sense, I probably have an innate distrust of a fashion designer who wants to make a movie. Someone who uses visual appeal to sell shallow products to shallow people now wants to create a deep work of art? I would expect that such a mentality would not lend itself to a cohesive narrative work of any great depth, and so I’m naturally on the alert that the whole thing will be a fraud. While A Single Man actually exceeds my cynical expectations, it is nevertheless plagued by a sheen of superficiality. It is characterized by pseudo-profound snippets of dialogue, alluring imagery, and a bare surface-scratching of its main themes.

Of course, you could take a number of stills from the film and use them as billboards for perfume or whiskey or clothes or makeup or what have you. It looks amazing. Every frame is crafted with utmost attention to visual detail, from the color palette to the set design to the shot composition. Likewise, the way that individual shots and scenes visually relate to one another seems thoroughly considered.

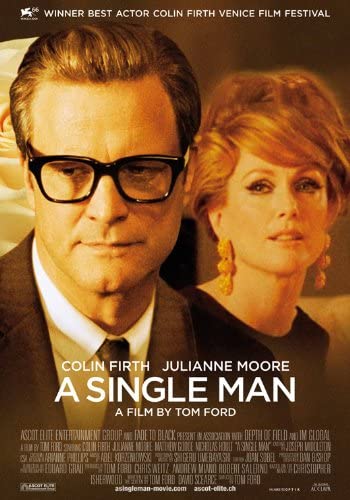

Less attention is given to the film’s narrative, which, on paper, should have deep emotional resonance. Instead, it is frequently dulled by a sense of calculated stylistic posturing that overpowers the themes of love, death, memory, and regret. It’s not that there’s nothing there, script wise, but given the effort put into the look of the film, the dialogue and voiceover monologues feel particularly lacking. This phenomenon is clearly illustrated when George (Colin Firth) visits his friend Charlotte (Julianne Moore) for drinks and cigarettes. Charlotte’s character is constructed entirely to provide a few key moments and look just right, so when her tone and manner fluctuate erratically, which throws us completely out of immersion, we must begrudgingly accept the caricature if we are to take the film seriously. And this is a film that is begging to be taken seriously.

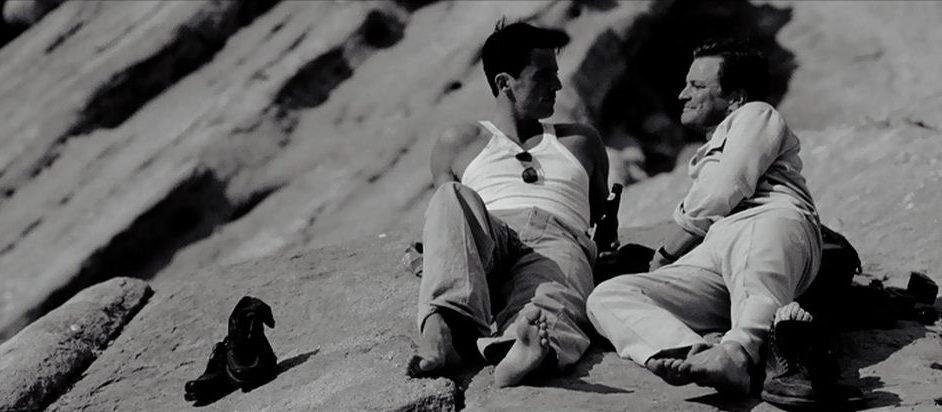

Part of the problem is that we must allow the contrivance that our single man gets caught in heartbreakingly wistful daydreams every five seconds. In the midst of both the grieving process over a dead lover (portrayed in flashback by Matthew Goode) and the Cuban Missile Crisis, George Falconer lives almost entirely inside his own head. He speaks to the audience almost as much as he does to other people, and when he does converse, his words nevertheless come out as memorized soliloquies. In the middle of conversations his eyes will drift and he’ll find himself immersed in a separate thought entirely. His eyes often fall upon the human body, which Ford is clearly enamored with, lingering on close-ups of lips and eyelashes and sweat-drenched torsos.

Beyond the pervasive appeals to sensual pleasure, though, the film is saturated with the notion of enchantment—cars, cigarettes, tailored suits, and home décor are shot alluringly in an effort to romanticize the aura of the 1960s. It is an interesting way to shoot a film that is entirely relayed through the eyes of a depressive who seems settled on the fact of his own impending doom. As George goes about his day, contemplating suicide, remembering the death of Jim and their shared history, these little moments of sensual arousal amidst the mundanity of every day life seem to give him pause. It becomes clear that, although George presents himself as a composed professional, he does not really have a firm grasp of himself. He idealizes his past and romanticizes his fleeting thoughts and feelings. He desires to relive certain moments, to stop time, in a sense—and this paralyzes him, leading to a pattern of destructive behavior where the thoughtless experience of sensation becomes a kind of end goal. A very shallow existence, but one that he confusingly accepts with a sense of fatalism.

A few times in my life I’ve had moments of absolute clarity, when for a few brief seconds the silence drowns out the noise and I can feel rather than think, and things seem so sharp. And the world seems so fresh as though it had all just come into existence. I can never make these moments last. I cling to them, but like everything, they fade. I have lived my life on these moments. They pull me back to the present, and I realize that everything is exactly the way it was meant to be.

Tackling such an internally focused narrative requires a strong performance, and I think Firth does a splendid job in capturing the spirit that Ford is striving for. The mannerisms and vocal affectations give us a sense of his struggles. Firth’s acting carries the film entirely. Without his contributions, the overtly surface level imagery and all the careful shot composition would amount to naught. The supporting roles from Julianne Moore, Matthew Goode and Nicholas Hoult are fine, but never really connect with our intensely inward-gazing central character. But maybe they’re not supposed to.

Despite Ford’s clear talents, he seems to misunderstand the role of the viewer in the commerce of art, choosing to hold our hand rather than give us interpretive agency. His employment of various color palettes proves he has a good eye for shot composition, but his overuse of the change-up becomes tiresome very quickly. Such an overbearing directorial style has its merits, but after a certain point the sensual, surface-level sheen starts to feel tedious and self-conscious, and actually actively detracts from the experience. It’s an unfortunate textbook case of style over substance, made doubly so by the fact that its feigned substance turns out to be a stylized caricature of it.