“You shouldn’t think of her as a woman. That would be a mistake.”

Steven Soderbergh isn’t afraid to fail. Neither is he hesitant to make controversial decisions for the sake of his work. Sometimes, his experiments result in top shelf films, while other times his efforts are too far off the wall to land with film snobs, let alone mainstream audiences. I don’t love everything he’s made, but I love the undying spirit with which he’s gone about honing his craft. Even his failures have an infectious buoyancy to them, revealing an underlying love of cinematic storytelling that has remained steady even as the auteur continues to discover new tricks through trial and error. This penchant for trying and failing rather than avoiding risk has led to a very refined and confident skill set that allows the director to pull off many tough tasks with seeming ease. Case in point are the superb action sequences in Haywire, which come early and often throughout the film. Anchored by ex-MMA and muay Thai fighter Gina Carano, the film’s choreographed combat sequences are simply exquisite. Without relying on frantic music, intense sound effects, or rapid-fire cutting and shaky-cam footage, these fight scenes play out in medium shot without blinking, giving them a palpable, brutal texture that is absent in standard action cinema.

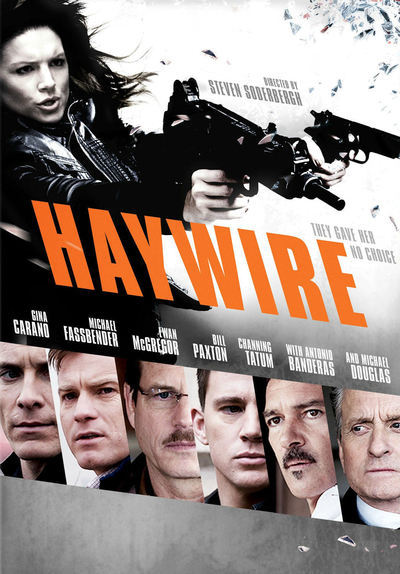

In 2009, Soderbergh’s The Girlfriend Experience—a modest slice-of-life experiment set during the lead-up to the Presidential election—caused a stir because the director cast Sasha Grey, an ex-pornstar, as the lead. Tapping Carano for the star role in Haywire might be less controversial, but also riskier, considering that the films’ budgets differ by a factor of ten. After competing in martial arts for a decade, Carano’s only acting experience prior to Haywire had been a small role in a direct-to-video film about martial arts, and here she is leading a cast that includes such stars as Channing Tatum, Michael Fassbinder, Antonio Banderas, Michael Douglas, and Ewan McGregor. While I’m not entirely swept off my feet by Carano’s performance, I think that her actual physical competence lends itself very well to the action-heavy role.1

Carano portrays Mallory Kane, a black ops kicker of butts on the run from her employers who suddenly wish her dead. We’re purposefully left in the dark for large portions of the film, left to question motives and character relations in the back of our minds even as our protagonist is running for her life. In the film’s opening scene, Mallory sits in a diner, bruised and scabbed, waiting. When Aaron (Channing Tatum) arrives, the two engage in a brief conversation, feeling out the situation, before he tosses a steaming cup of coffee into her face and attacks her. A gun is pulled, shots are fired, an arm is broken, and Mallory escapes in a bystander’s car with the bystander in tow to help patch up her bullet wound. It is a rare occurrence for raw choreographed action to make my jaw (figuratively) drop. I’m much more easily swayed by narrative elements and creative shots. But I’d be lying if I said this scene, and several others that followed it, didn’t have me sitting up and paying attention. It was some combination of the lack of sonic adornment, the clear-eyed distance from the action (we’re more spectators than participants), and the scarcity of cuts relative to expectation that made it so pulse-raising.

The screenplay by Lem Dobbs (Dark City, The Limey) weaves a deceptively complex story that puts Mallory into a series of situations that demand physical and tactical skills. It ultimately amounts to a bunch of meaningless intrigue but it does a fine job of sucking you in. From Barcelona to Dublin to Mexico, Mallory poses as an M16 agent, is chased across rooftops, and uncovers a nefarious plot to frame her for murder. The writing is restrained but constructed and adorned carefully to avoid falling into the standard spy-thriller mold.

To help account for Carano’s inexperience, Soderbergh surrounds her with consummate professionals. Ewan McGregor plays Mallory’s shifty employer/former lover; Michael Fassbinder is a sophisticated M16 agent; Michael Douglas is a U.S. official trying to court Mallory into the federal ranks; Antonio Banderas is a grey-bearded puller of strings; Bill Paxton portrays Mallory’s father, a writer of military nonfiction. It’s okay if you get confused about who is good and bad, or even who works for who (I think that’s part of the point). Even though the plot is sometimes hard to follow, the characters are fleshed out impossibly well for a ninety minute film. The ensemble, firing on all cylinders, does an outstanding job of elevating one another such that one could be forgiven for mistaking Carano for a well-practiced movie star.

What really makes the film shine—what allows it to be more than “just another spy movie”—are the considered cinematography and creative editing. Soderbergh handles both these duties under pseudonyms, crafting his film into a streamlined, efficient little beast. A subtle but effective use of color filters helps us shift locations. Unconventional camera positions keep us engaged during long periods of scant dialogue. A restrained use of music lends weight to the brutal fight scenes where Carano unleashes her honed abilities, which are highlighted even more by Soderbergh’s often unmoving camera.2 Having considered the film for a few days, I think what is most jarring about these fight scenes is that there are no visible stuntmen (or women). The cuts required to substitute prior to crashing through windows and getting kicked in the face simply don’t occur.3

Another noteworthy element of Haywire is its adamant refusal to sexualize Carano. There is one scene where she uncomfortably wears a dress, and another where she and Tatum lick each other a bit, but these both have narrative significance and feel in-character. Contrast this with the sexualized action performances of, say, Angelian Jolie or Scarlett Johansson. A lesser film would have leaned into the notion of a sexy action hero, removed several articles of clothing, etc. They also would have paid a model way too much money to fake her way through action scenes. Celebrities pretending to be lethal combatants are already hard to take seriously as such, and the inclusion of excessive sexualization often detracts from the believability even further. Haywire smartly avoids the needless titillation and is better for it (although this is probably also why it didn’t make a ton of money and didn’t become a franchise). Throughout, Carano’s hardened persona remains intact, and thus her character remains frighteningly capable of committing real damage long after a lesser film’s star would have become a caricature.

By avoiding most of the genre’s clichés, casting a relative unknown to lead a star-studded ensemble, and shooting fight scenes realistically, Steven Soderbergh has created a singular spy thriller. It’s modest, for sure, and probably won’t be remembered by many, but a first-rate director taking on an unfamiliar genre, one usually marked by sex appeal and silly contrivances, and turning it into something very good is always welcome.

1. That’s not to discount the crazy training regimens that actors routinely endure to portray beefy characters; but let’s not kid ourselves and say that a roided macho man or toned woman carry themselves with the same lethal swagger as a real professional fighter.

2. Consider the contrast with something like The Bourne Identity and its legion of copycats, which use shaky-cam to make fight scenes intense (and often nauseating).

3. I don’t know anything about the film that you can’t read on the internet; I’m just going by what I see. It’s possible there was some stunt work or subtle use of CGI. But it certainly appears that some super impressive choreography is going on.