“It’s a uniquely human fantasy that things will get better, born perhaps of the uniquely human understanding that things will not.”

I tried to describe Charlie Kaufman’s latest pensive mind-bender to my wife—who dislikes ambiguity in movies—in such a way as to make it appealing to her. That means I had to begin the story with the ending, which provides the biggest clue for understanding the brain tickling that occurs for the preceding hour and forty minutes. After my long-winded spiel about the intricacies of the film, she pierced right through my charade and said, “But you don’t actually know any of that while you’re watching the movie, right?” I admitted that she was correct, then amended: “Well, you don’t necessarily understand any of that once the movie’s over, either.” She’s partial to the cut-and-dry, you see, while I prefer films that linger in the subconscious, that reward repeat viewings, that make you think about their central themes outside the scope of the films themselves. I’m Thinking of Ending Things, Kaufman’s third effort as a director, checks all those boxes. Its initial presentation as a psychological horror film sucks you in, but it unfolds into an exploration of the human condition—an unsolvable puzzle with which Kaufman is well acquainted. It was a joy to watch and I’m hopeful that it will age well.

Let’s paint the initial picture to get ourselves oriented. For those of us who’ve worked at a monotonous manual task, say, splitting firewood or pulling weeds, there’s a familiar freedom of thought that results. It also happens to me sometimes when I’m reading either a particularly dry book. On the other end of the spectrum—working a desk job and staring at a computer all day, bombarding oneself with useless information and blue light—there’s essentially no opportunity for unconscious thoughts to bloom. In the former case, the wandering hours can lead to some very intricate and well-developed internal fantasies. I specifically recall trying to hold entire story ideas in my head while hiking for double digit hours each day on the Appalachian Trail. It’s amazing what the mind is capable of when disconnected from constant technological stimulation.

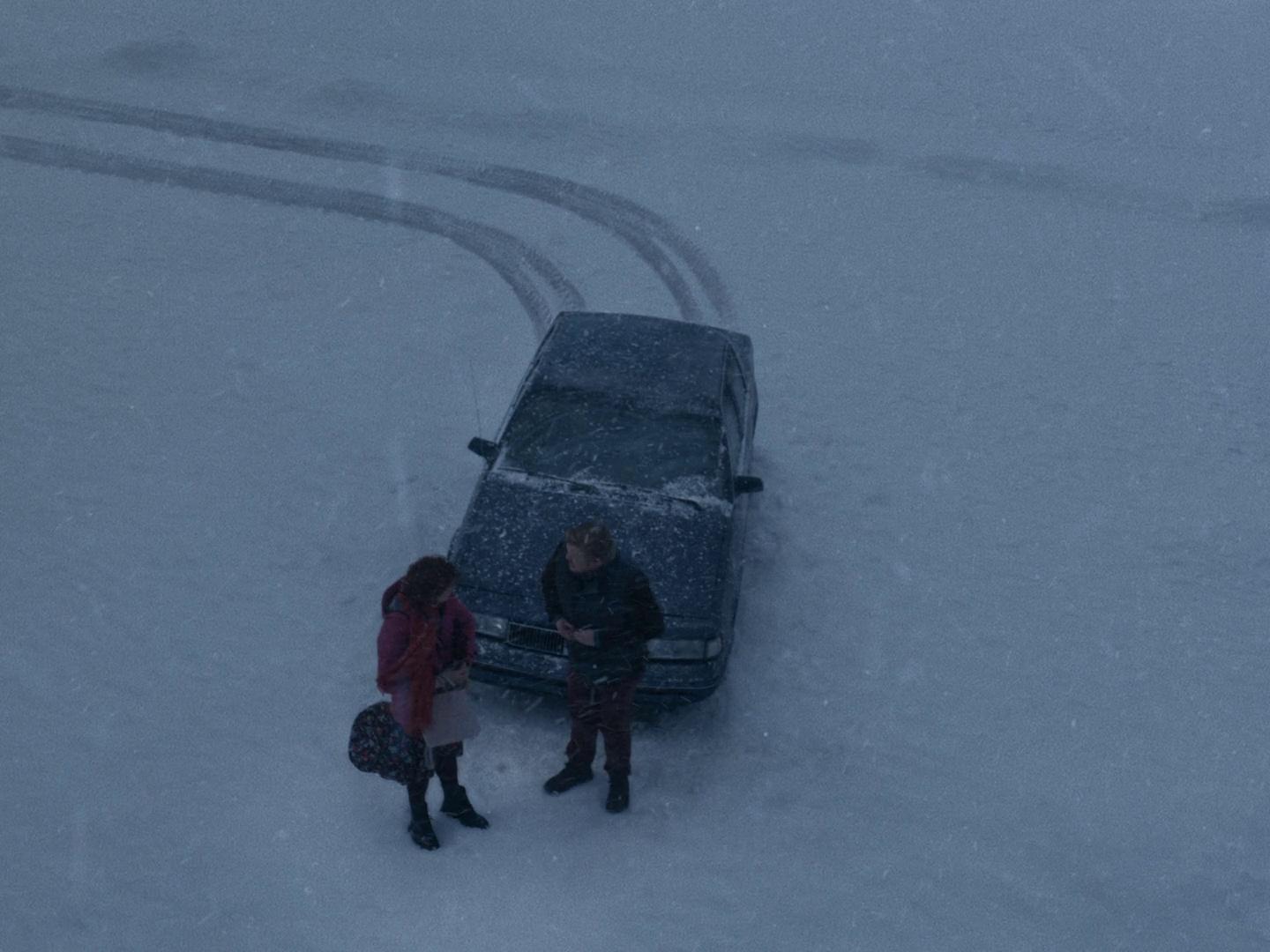

The main narrative of I’m Thinking of Ending Things tells the story of Jake (Jesse Plemons) taking his new girlfriend to meet his parents for the first time. The girlfriend, portrayed by Jessie Buckley, is variably referred to as Lucy, Louisa, Lucia and Ames. Her occupation is dynamic as well, another of the many clues that gradually build an eerie sense of unreality. The reason for this morphing characterization has something to do with the interspersed snippets of an old janitor (Guy Boyd) working at a high school, viz., the old janitor is actually Jake and our main story is his imagination in overdrive as he pines for the life he never lived. There, I’ve spoiled the whole movie. Not really, though. That’s not a big revelation, at all. There are clues suggesting it throughout—the uniforms that Lucy finds in the washing machine, Jake’s obsession with the musical Oklahoma! paired with the old janitor watching rehearsals of it. Enjoyment of the film is not tied to its twists.

The allure of the film is twofold. First is the way in which Kaufman carefully builds the intricate interior life of Jake and clues us into his bewildering state of introspection. Thoughts and accomplishments are shared between characters, Jake’s parents age and de-age between scenes, and at one point Lucy mistakes a childhood picture of Jake for one of herself. The surreal dinner scene with Jake’s parents—brilliantly portrayed by Toni Collette and David Thewlis—turns into a nightmare of exaggerated character traits. On the ride home, the couple engage in a detailed discussion of John Cassavetes’s A Woman Under the Influence. Lucy uses weird turns of phrase that Jake segues into specific discussions on obscure topics. There are myriad little details that serve to paint a vivid portrait of a confused mind that regrets a lifelong predisposition toward inaction. He’s creating a fiction to help keep those feelings at bay, but, in his dreamy state, cannot keep the details straight. He can’t even keep his characters from overlapping and must resort to his repertoire of memorized media to flesh out his love interest.

The second element that makes the film so charming and slippery is that, on top of all the obfuscation, the story is largely told from the point of view of Lucy—a person whose existence stems almost entirely from Jake’s imagination. Any concrete details of their first date get lost in the retelling, to the point that we’re not even sure they ever actually met. Many of the film’s most hair-raising moments come from the lack of depth in Lucy’s character that must be filled in with Jake’s own thoughts and ideas. For instance, after a lukewarm reaction when Lucy shows Jake’s parents some of her paintings, she discovers the same paintings in the family’s basement. In another case, she finds a book of poetry in Jake’s childhood bedroom that includes a poem she had recently written and recited for Jake on the car ride there. Sometimes Jake seems to hear Lucy’s internal monologues. Because Lucy (and the audience) try to hold onto the fiction that she is real, we are caught off guard with her when these confrontations with the surreal occur; when she realizes that her fleeting form is merely an assemblage from the books and movies that have fed Jake’s idea of womanhood during his decades of reclusion.

Ultimately, the concrete details don’t matter, as hard as that is to stomach for movie-watchers who prefer everything tied up neatly. “I’m thinking of ending things” could refer to the relationship or to suicide; Lucy might actually exist, or not; it doesn’t really matter. Kaufman’s reaching towards universals. The haunting backdrop is used as a lure to get us to his introspective discussions of aging, desensitization, and media saturation; our penchant for constructing fictional versions of others in our minds based on our limited interactions with them, our wistful longing to rewrite the past, our predilection toward viewing ourselves as the center of the universe. And in typical Kaufman fashion, there’s no preaching here. Rather, we merely observe. We back out of the comfortable routines of life, pop our heads above water for a moment, and realize just how strange everything is.

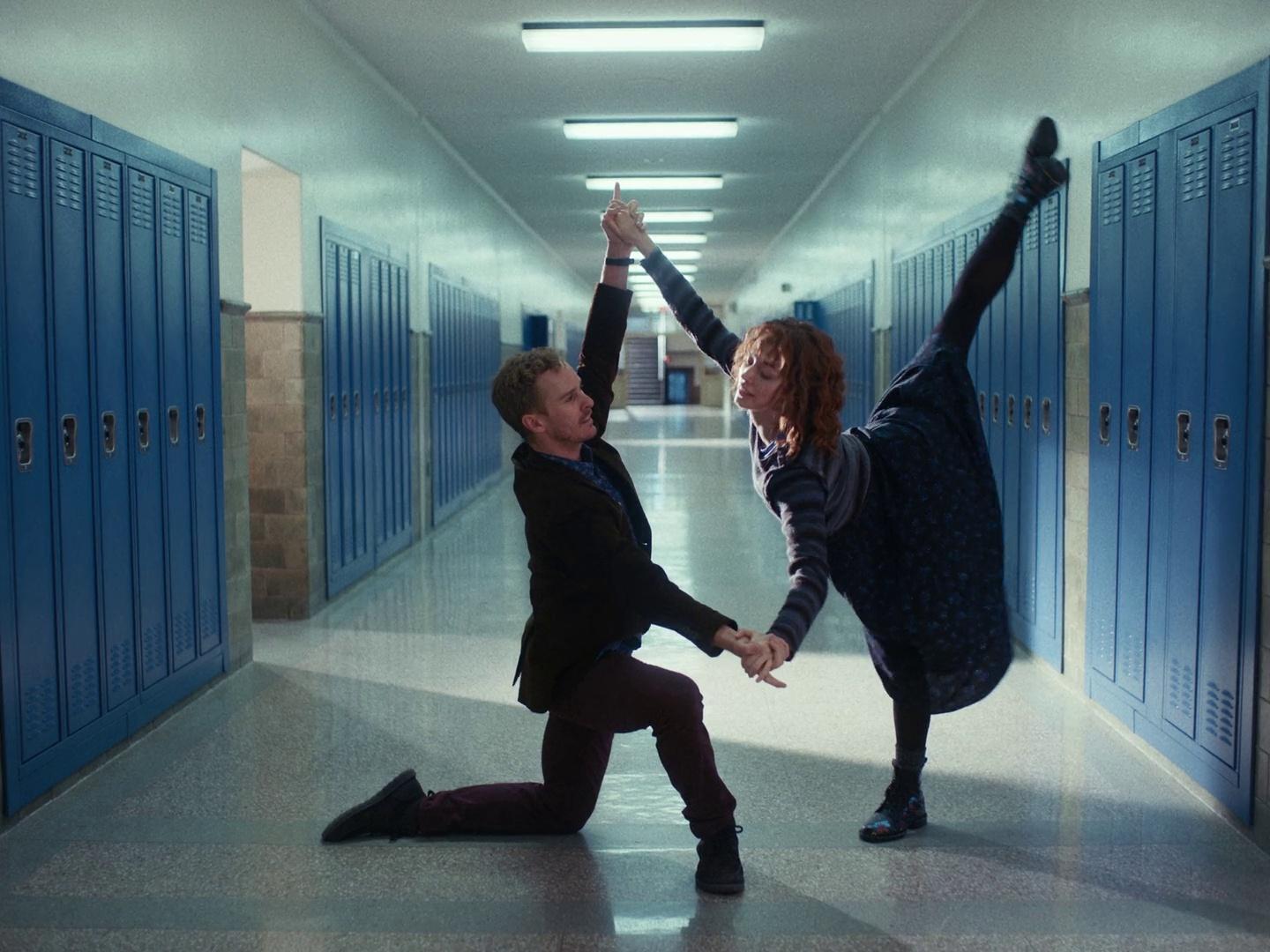

About two thirds of the way through the film, with some of the hard evidence still withheld, I’m Thinking of Ending Things could have gone any number of directions. I was not expecting the bold move to climax with a symbolic ballet and a musical number. The ballet, performed by Ryan Laughtner Steele and Unity Phelan as stand-ins for the main characters, is a huge left turn. It reminds me of a similar narrative departure in Francis Coppola’s Tetro. I think the reception of this unexpected veer will determine what the film’s reputation will look like in the future.

In the film’s penultimate scene, Jake is on the stage in his old high school. He recites the idealistic Nobel Prize acceptance speech from A Beautiful Mind, a film that deals with how one absorbs their experiences into their own psyche (among other things). In fact, a survey of the “works cited” in Kaufman’s film—David Foster Wallace’s A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, Oscar Wilde, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality, Pauline Kael’s review of A Woman Under the Influence, Anna Kavin’s Ice, Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle—goes a long way in informing us of the mind space that Kaufman was puttering around in when he wrote the screenplay. (Of course, it must be noted, many of the details come from Iain Reid’s novel, although the endings diverge, with Kaufman jettisoning Reid’s literal turn for the symbolic.)

Although I don’t agree with the insinuations made by the film—that maybe there is no objective reality—I find Kaufman’s brand of existential groping to be endlessly fascinating. Tinged with melancholy, teeming with high brow references, and lacking a clear-cut resolution for its plentiful loose ends, I’m Thinking of Ending Things isn’t looking for a huge audience. But the niche in which it belongs, alongside Kaufman’s other triumphs like Adaptation, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Synecdoche, New York, is comprised of people that will truly connect with it.