“Then I’ll show you that starry, starry sky, like I promised I would.”

Millennium Actress is a mesmerizing breakneck puzzle that is fascinating to watch as its scope blooms. Occasionally you’ll come across a film where a plot summary cannot even scratch the surface of what it contains. This film is one of them. On paper, it is about two documentarians who interview an elderly actress, while intercut with the interview are scenes remembered from her life, embellished by her decades of lived experience since they were formed. Pitching such a description would be a non-starter for many movie-goers. It offers a further unique challenge in that the most qualifying descriptor one could add would be that the anime film was directed by Satoshi Kon, but anyone who already knows Kon likely knows of this film as well since his output was so small. The film is not really about its story, instead it has a very “meta” focus, offering a surreal, interconnected storyline that comments on the unreliability of memory, extreme fandom, the celebrity vs. the underlying human person, and the fleeting innocence of childhood.

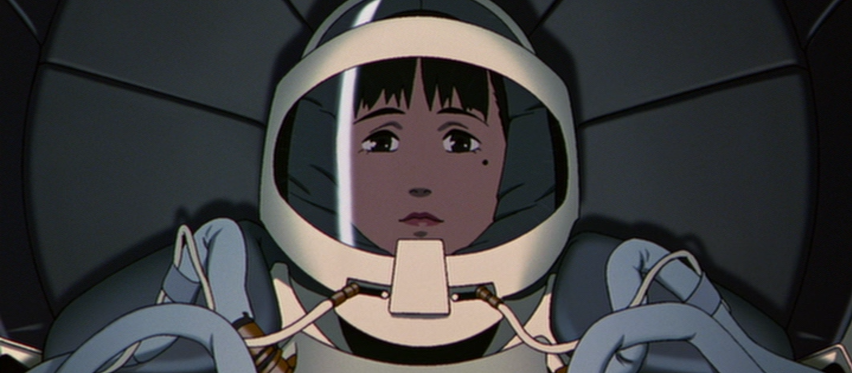

The film centers around the character of Chiyoko Fujiwara, an aging recluse, famous from her extensive film career. She agrees to be interviewed by diehard superfan, Genya Tachibana, prompted by the demolition of her former studio. Before the interview begins, Genya surprises Chiyoko with a gift—a memento which he believes she had lost many years ago. Perhaps prompted by the object, her mind swirls with emotion as she divulges memories from her childhood, adolescence, and career in cinema. In her youth, by chance and impulsive decision, she had met and safeguarded a rebel artist from whom she had first received the key that Genya brought for her. Her desire to be reunited with this man subsequently informs her life’s decisions, from where to live to which films to act in, and profoundly influences her memories.

As the interview with Chiyoko begins, we don’t just listen to a retelling of her story, and we are not simply transported to her memories. Instead the interviewers themselves are transported into the memories, which are now colored by the actress’s decades of life experience, and the scenes evolve into a cyclical narrative about her quest to find the activist painter whom she met only briefly as a child. Genya’s insertion into the memories has the most visceral impact. He cries during scenes, is visibly distraught, and even takes on the role of Chiyoko’s protector in a scene from one of her films. As the latter scene ends, the film cuts to the interview, where Genya and Chiyoko are reenacting the scene in the present. Genya’s antics can easily be read as superficial humor, but as the story unfolds we begin to uncover the formative episodes in Genya’s life that led him to become such an admirer of Chiyoko. Additionally, though his actions are exaggerated, they do not feel over-hyperbolized compared to the superfans of movie franchises, actors, bands, etc. (Consider The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which regularly features shadow casts in full costume acting along as the film plays on the big screen; or even something as simple as cosplaying at Comic-Con.) The cameraman, Kyōji, grounds the film quite a bit. He openly questions how they are even there, subtly preventing the viewer from being drawn too far into Chiyoko’s memories.

The film can be somewhat dizzying with its editing and narrative styles. The jumbled sequence of the story alone requires the viewer’s undivided attention, but the scenes also bleed together using smooth transitions which distort reality as we become unmoored in time and space. It is often up to the viewer to interpret what is on screen and determine if we are looking at a memory, a movie scene, or some amalgamated reminiscence. The people in the real world often overlap into her memories of the films she was in, and her memories of people are often warped by the characters they portrayed on film. For instance, the government agent pursuing the dissident painter in real life is often cast as the villain in the memories of Chiyoko’s films. Kon’s other works, such as Paprika, and Perfect Blue utilize similar editing techniques to great effect as well.

Chiyoko’s story begins with the feel of melodrama as she aligns her life to pursue a man she barely knows. But as the film goes on, we learn that Chiyoko doesn’t really remember the man at all, and is perhaps longing for the childhood naivety that allowed her to become enamored with the charming renegade in the first place. Throughout the film, Chiyoko is periodically confronted by a wraith of an old woman who haunts her memories. She can be read a projection of Chiyoko—a possible future version of herself that she does not wish to become. As the artist tells Chiyoko, “after the full moon, everything starts to wane.” By chasing him she stays connected to her youthful vigor, and her enchantment never wanes. Kon’s storytelling is masterful, and the concluding scenes gradually pull the disparate threads into a unified theme in a poetic and poignant coda. Despite a pervasive sadness throughout the film, its ending feels positive and life-affirming.

When Chiyoko is given the key, it is intuitive to use that as a grounding mechanism to determine if we are in the real world or a fictional one, sort of like the spinning top in Interstellar. However, this turns out to be intentionally misleading, as is the key itself. When the painter gives it to her, he tells her that “it unlocks the most important thing,” a line she repeats to the interviewers when Genya presents her with it. We never learn what the most important thing is, though it certainly is not a physical object. It could be creativity, motivation, or innocence. But the only thing it unlocks within sight of the viewer is Chiyoko’s memory. Regardless of how it was unlocked, it is both sensible and poetic to consider memory paramount. As we age, our memories form the individual people that we become. But as they fade, we can lose little bits of ourselves that were once crucial. Having those memories triggered again after lying dormant for years can be a powerful emotional experience, evoking melancholy, nostalgia, or regret. This human phenomenon of self-mythologizing is portrayed exquisitely in Millennium Actress.