“Where are they? Where are your friends now? Tell me about the loneliness of good, He-Man. Is it equal to the loneliness of evil?”

Movies based on toys almost universally suck. Masters of the Universe is not only based on a toy, but that toy line began as a ripoff of another toy which is based on another movie. Basically, Mattel decided to turn down Star Wars and then responded to the toy line’s success by creating He-Man, perhaps the most generic action hero in existence. Steroided, blonde and tan, the 5.5” action figure and his companions were a hit. This meant that the MOTU franchise got the whole nine yards of merchandising—stacks of comic books, read-along cassettes, trading cards, a float at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, and hundreds of hours of animated television that gave He-Man a backstory as Prince Adam of Eternia. It’s a beautifully amorphous setup that allows for sword-and-sorcery and hi-tech futurism as He-Man engages in a perpetual war with his nemesis, the blue-skinned, skull-faced Skeletor. By the mid-1980s the franchise was raking in hundreds of millions in revenue each year and a live-action film was an inevitability. Masters of the Universe came out in the summer of 1987 and is about as crude and silly as you’d expect from a children’s toy line cash-grab. Unfortunately, it takes itself as seriously as the more grounded franchises it is derived from, and it’s hard to tell if it’s the endearing kind of awful. But still, if this were made today, it would be a CGI-fest, so some credit is due to this cheaply produced microcosm of 1980s entertainment and its quaint charm.

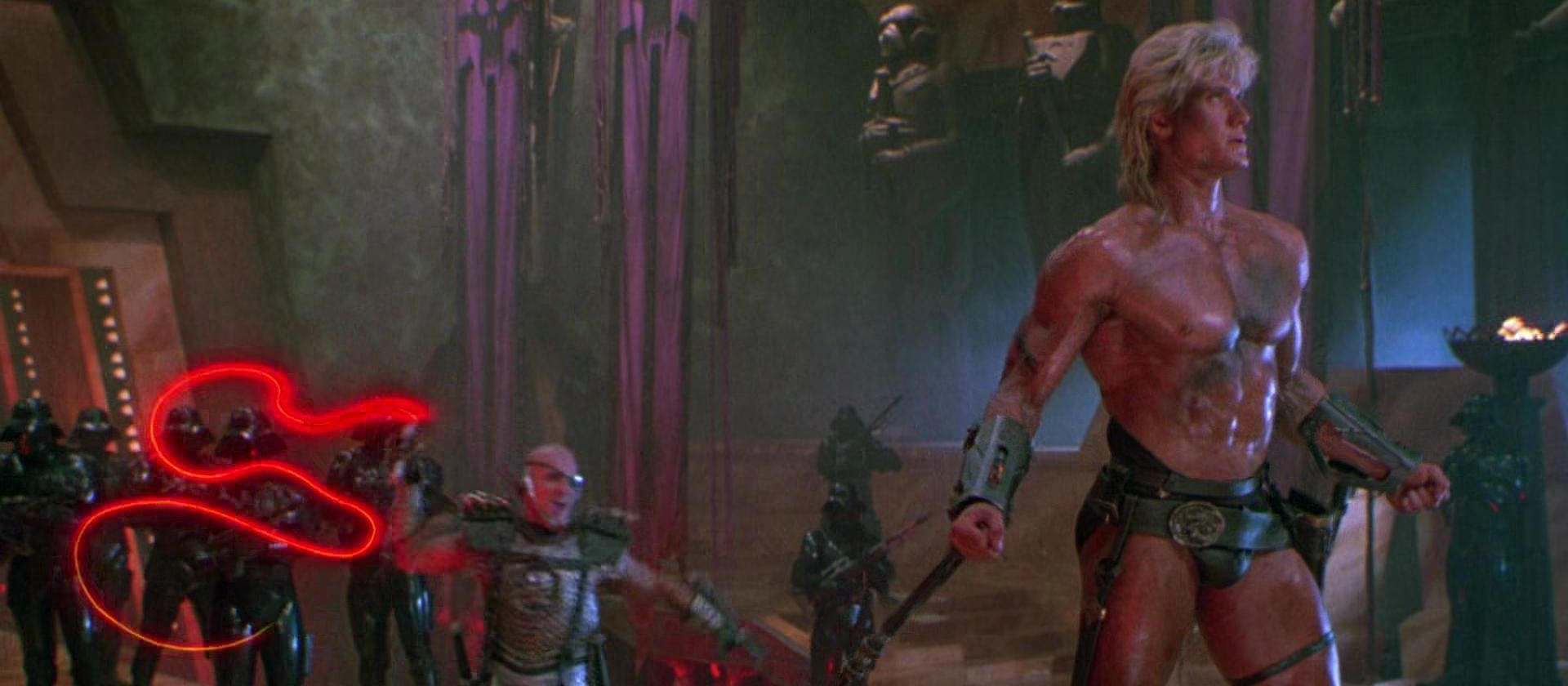

The screenplay whittles down the messy world of the MOTU comic books and television show and contrives to have He-Man (Dolph Lundgren) and his various sidekicks travel from his home planet of Eternia to Earth. This is accomplished by a spiky synthesizer device known as a ‘cosmic key’ created by a dwarf/troll named Gwildor (Billy Barty) that rips through the fabric of space-time if you play the right notes on it. California isn’t quite the same fantasy setting as Eternia—I assume the budget dictated they shoot in backlot rather than a fantasy setting—but at least they have good fried chicken there. Along with Man-at-Arms (John Cypher), Teela (Chelsea Field), and Gwildor, He-Man sets out in search of the key, which was lost during their space-time jump. Skeletor (Frank Langella), who already has a copy of the key, is also searching for He-man’s because he believes it will make him omnipotent—so he sends Evil-Lyn (Meg Foster) and some other cronies to Earth to fetch it. But before either our hero or our villain get their mitts on it, the key falls into the hands of Julie (Courtney Cox) and her boyfriend Kevin (Robert Duncan McNeil), who thinks it’s a Japanese instrument and tries to incorporate its sound into his band’s music. This wackiness culminates in a battle between He-Man and Skeletor back on Eternia.

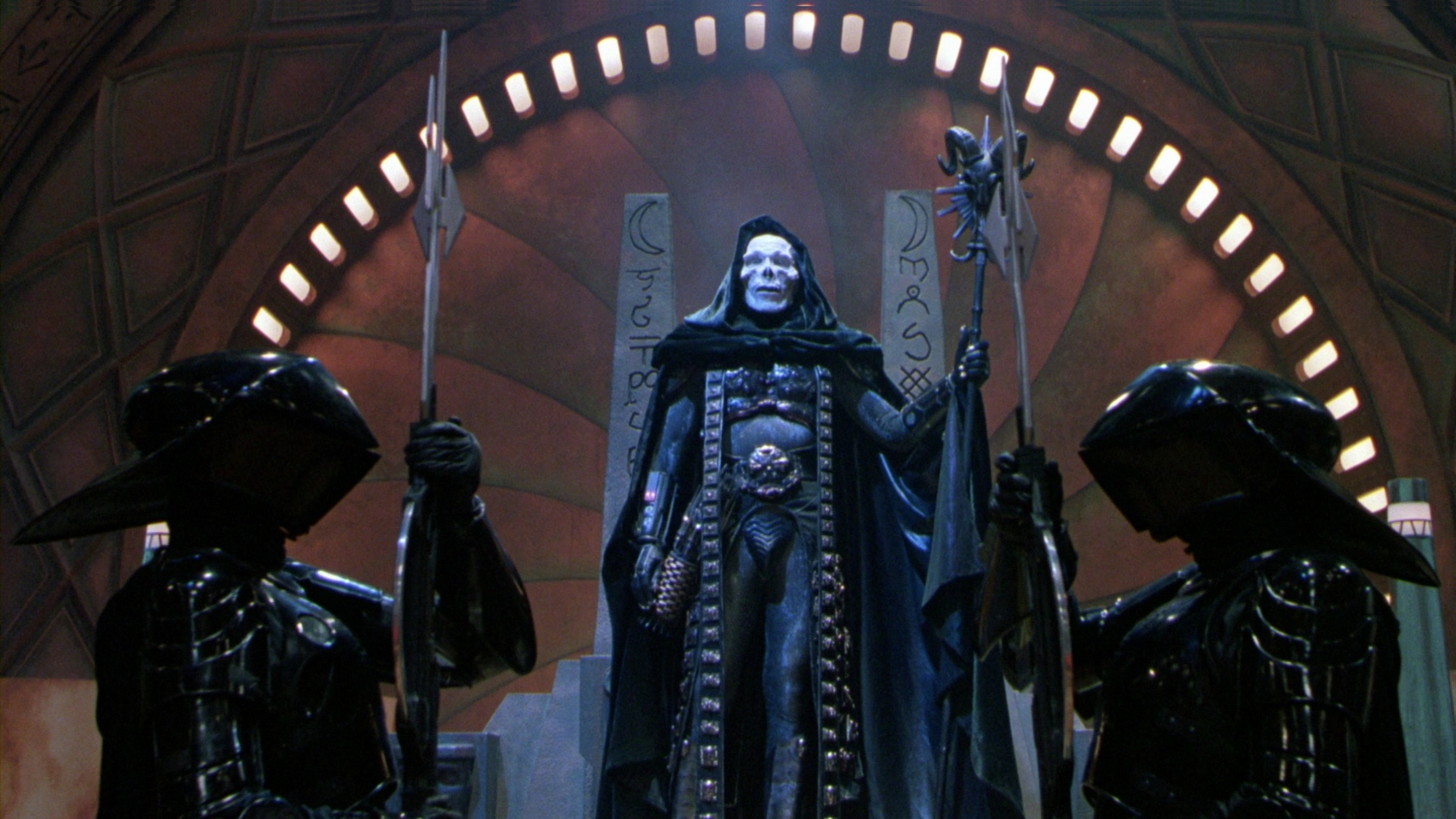

Frank Langella as Skeletor is the highlight of the film. Because the script is so poor, there is no rhyme or reason to his menacing demands—including the desire to have He-Man taken alive—but this lack of motive makes his slippery shenanigans interesting to witness. Langella took the cheesy, make-up heavy role because his son was a big fan of MOTU, and he commits to each scene with gusto. He seems to have had a lot of fun playing the character and claims he doesn’t regret it even though the film was negatively received. Cox’s performance is the only other one that rises above the level of cringe-inducing. Lundgren, in particular, is horrible as a Schwarzenegger knock-off in his first starring role. He looks great with all his muscles and whatnot, but he’s wooden, uncharismatic, and barely speaks. When he does, though, whoo boy. He was so unsteady with his English that his contract stipulated he only had three attempts to get his lines right or else they’d dub him with a voice actor. Since he was able to say the lines, Cannon executive Menahem Golan honored the contract and kept the lines in. Lundgren was a Fulbright scholar with a black belt in karate and Master’s degree in chemical engineering. It remains unfathomable to me why such an intelligent and skilled man would choose to be a star of low-budget action movies, but I guess that’s his prerogative.

It is clear that Masters of the Universe was compromised from the very beginning, when Skeletor captures Castle Grayskull. The cartoon series involves Skeletor and other villains routinely attacking the fortress with the belief that it contains secrets that would allow them to conquer Eternia. Having this happen off screen before the film even starts feels incredibly cheap, even to someone like myself who has no nostalgic connection to the franchise. I’m vexed on behalf of all those young kids who were caught off guard by the random transportation of the setting to Earth. “Cheap” describes much of what we see in Masters of the Universe. Director Gary Goddard claims budget cuts and delayed wages as reasons for the film’s ramshackle quality, though who deservs the lion’s share of the blame is up for debate. No one really brought their A-game. But some of these badly scripted scenes somehow turned out to be splendid moments of kitsch, such as Teela (Chelsea Field) inexplicably breaking the fourth wall, Gwildor trying to talk to a cow, or Julie not questioning the nearly nude bodybuilder with a sword who just lifts her off her feet.

From script to casting to production, it amazes me that anyone ever took this seriously enough to be disappointed in how awful it turned out. Goddard does his best to give it some semblance of coherency, and Bill Conti’s score way overshoots the material it is attached to. But the behind-the-scenes shenanigans that derailed the production are almost as kitschy as the final product. In the decades since its release, Masters of the Universe has garnered some momentum as a cult film. The bargain-bin set design, ridiculous costuming, and silly dialogue, whether from Langella’s committed performance or Lundgren’s thickly-accented one, all lend themselves toward a campy enjoyment of the film. Let’s just hope the fandom remains tempered enough to prevent a major studio from scooping it up and giving it the modern superhero treatment. That would be a real travesty compared to this quaint, oddball time capsule of 1987 entertainment.

Sources:

Burwick, Kevin. “Dolph Lundgren Only Had 3 Chances to Get His He-Man Lines Right”. Movieweb. 7 August 2017.