“You looked inside me…”

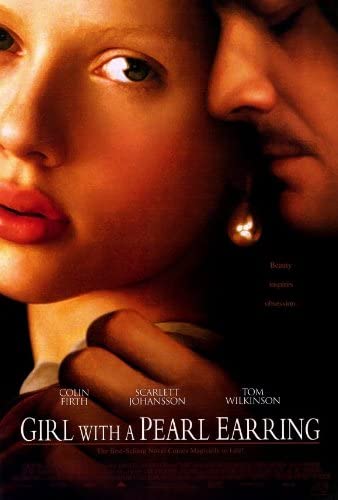

So little is known about the life of Johannes Vermeer that author Tracy Chevalier was able to fabricate a story out of whole cloth to explain how the painter’s famous piece came to be. Having purchased a print of the painting when she was a teenager, she looked at the confused, unreadable mixture of emotions on its subject’s face for over a decade, and came to believe that this inscrutable visage was a response to Vermeer himself. Her imagined backstory centers around a servant girl named Griet, who is sent to work as a maid in Vermeer’s household when her own father goes blind and quickly develops into something of a muse for the artist. When he finally paints her wearing his wife’s earrings, her glance is a confused blend of admiration, infatuation, and fear. This fanciful conjecture was a big hit with readers and television director Peter Webber was tapped to direct the film adaptation as his feature debut. Colin Firth stars as Vermeer while Scarlett Johansson, fresh off of her breakout role in Lost in Translation, plays the taciturn Griet.

Lensed by Eduardo Serra, who captures the handsome cast in their period costumes with a practiced hand, the film’s lush aesthetic sensibilities are hard to deny. There are few frills as far as camera movement or editing, but each frame’s composition is carefully considered. The set design, which captures the canal streets of Delft (although filmed elsewhere), marketplaces, and a variety of interior locations, has a lived-in authenticity a cut above the usual television period drama. The color schemes, lighting, camera placement, and the careful mise en scène all support the film’s painterly aspirations. This lavish visual quality is the film’s calling card, and it is fortunate that it is such an overpowering element, because in many other respects it is lacking.

The problems arise when we try to move beyond visuals and get into the narrative, which is uneven at best. The central issue, which I’ve surmised by scouring the wild west of the interwebs for summaries of the book, is that large portions of the text are interior—meaning they occur in Griet’s mind. That’s great for a book, but not so great when that’s your main character in a narrative film. It takes a lot of work to get a novel like that translated properly to the screen, and they didn’t really put in the effort here, it seems. Instead, we’ve got a lot of Johansson relaxing into a sort of moony, open-mouthed gaze where she just stands there aloof and uncertain, keeping her internal thoughts walled off from the audience. Since we never understand anything about our main character, she becomes a mere victim of circumstance, pulled into whatever situation presents itself to her. This may have been some kind of commentary on class or sex differences in the time period, but it simply doesn’t make for good cinema.

The narrative is doubly hamstrung by its thin quality. There’s simply not enough happening between the characters for the necessary engagement from the audience. Vermeer, the talented but eccentric artist, spends his days locked away in his studio. His emotionally neglected, perpetually pregnant wife Catharina (Essie Davis) hates Griet because she is young and beautiful and “understands” her husband’s artistic whimsies. However, their relationship is encouraged by his mother-in-law, Maria Thins (Judy Parfit), a strict woman who appears to mooch off of her daughter’s family—though I won’t pretend to know what was customary in Holland at the time—and questions his every decision. Maria Thins wants Griet to spend more time with Vermeer because she seems to inspire the temperamental artist to work and stirs up some passion in him; and since his paintings are a source of income, his talents must be exploited for all they’re worth. Initially worked to the bone scrubbing dishes, preparing meals, and washing clothes, Griet now finds herself going to the market to buy pigments and mixing paints for her master. Vermeer’s primary patron, Pieter van Ruijven (Tom Wilkinson), who routinely knocks up his own maids, requests that Vermeer let him have Griet. He is denied and settles for a painting of her instead, the titular piece which became known as “The Mona Lisa of the North.” The only other character with substantial activity is (inexplicably, since this is fictional) another character named Pieter (Cillian Murphy), a meat merchant who acts as a distracting love interest for Griet but really just gives her a sexual outlet when she’s lusting after Vermeer.

The most interesting scenes occur once Griet becomes a welcome presence in Vermeer’s studio and van Rujiven commissions her portrait. Although I found that Firth and Johansson didn’t really have the requisite chemistry for such an intimate relationship, there are several moments—such as when he pierces her ears, when he asks her to moisten her lips while he paints her, when he places his cloak over both of them to look into his camera obscura, or when he steals a glance at her unbound hair—that had a very palpable sense of erotic tension—although nothing improper actually happens between them. My favorite moment is when Vermeer asks Griet to tell him what colors she sees in the clouds—first she sees white, then grey, then after some prompting she sees yellow and blue and her artistic instincts are awakened. The creative closeness that develops between them is one that Catharina has never experienced, and pushes her to a moment of outburst in which she nearly ruins the painting out of jealousy.

Perhaps a layer below its sparse narrative, Girl with a Pearl Earring has something substantial to say about art, the relationship between the artist and his subject, classism, exploitation, what have you. The only one that is made clear is sexual repression, but I already said I don’t think the two leads really connected enough to make it work. You can call their sexual tension understated, or whatever, but you can also say it’s just not that good. The film is so concerned with showcasing visual splendor that it holds everything at arm’s length. These characters look authentic but their interactions feel clinical and calculated which leads to a lack of engagement. There is a lot of talent assembled here, and many of the pieces come together quite well, but it just didn’t jell as well as it should have.