“When you were my age, you all wore brassieres that made your tits stick out like torpedoes.”

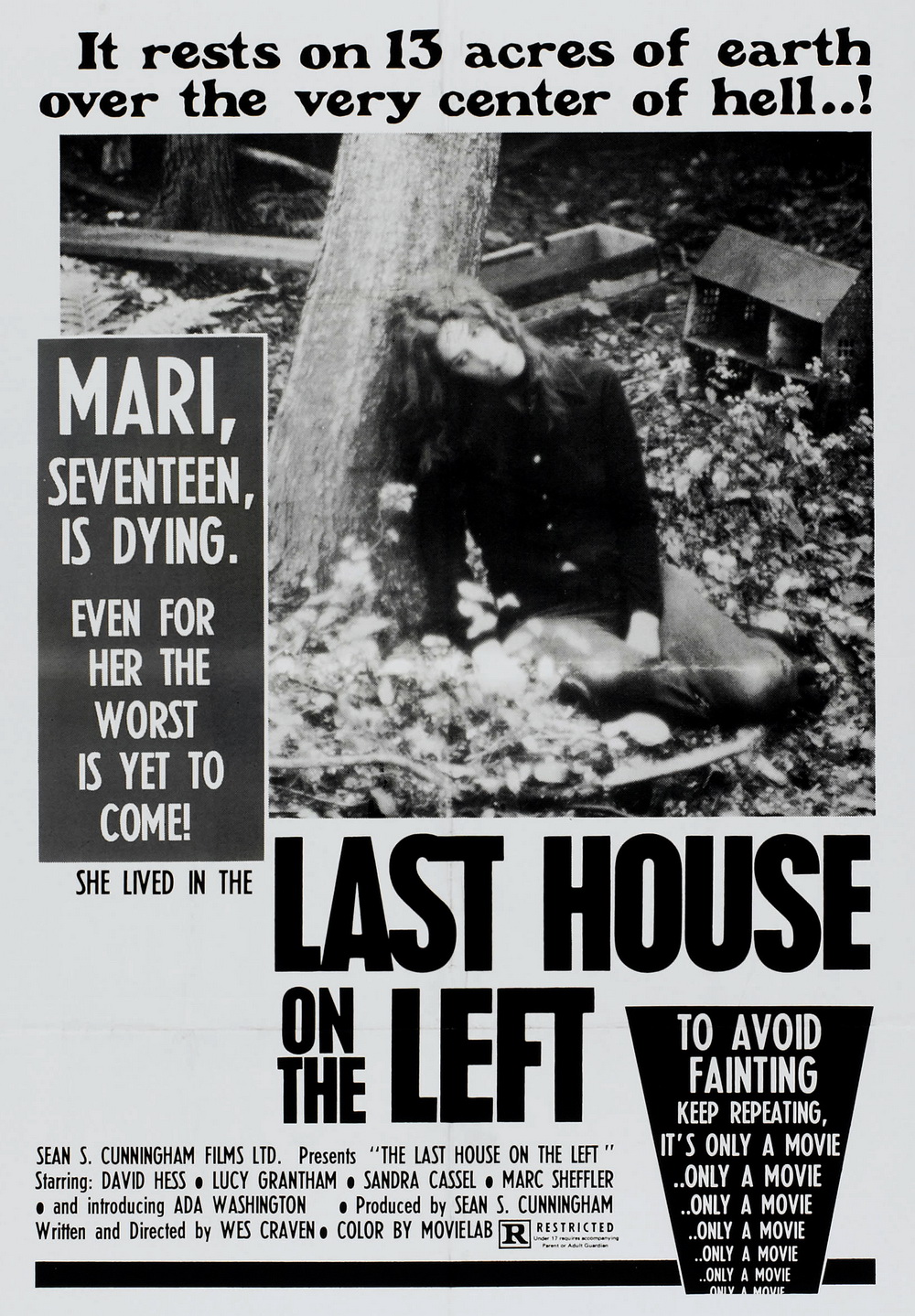

Like many seminal horror films of the 1970s, The Last House on the Left was shot as cheaply as possible. Long takes, close ups, a loose script, improvisation, guerilla shoots, and grainy visuals give it a pseudo-documentary feel that puts a brutal emphasis on the “crime of the century.” First-time feature director Wes Craven, who had cut his teeth in the X-rated pornography business after abandoning a teaching career, brought his burgeoning skills to the horror genre to make a low-budget slasher flick that he thought no one would see. Many of the stylistic choices are natural consequences of shooting a film for little money, but together they serve as an excellent platform for the provocateur to do his thing. Once, without any foreknowledge of the contents of the movie—other than that it was a horror classic (I was expecting something like Halloween)—I tried to watch this with my girlfriend. She’s quite a bit more sensitive than I am, but even I felt inclined to turn it off very early on due to the pure evil that is so effectively captured here.1 When I finally approached the film again, I did so with an understanding of Craven’s aims, the negative early reception of the film, and its subsequent rise to cult classic status. Too much of the runtime is dedicated to absolute depravity, and it seems to delight in human suffering too frequently, for me to truly love it. But the depictions of evil are counterbalanced by a tonally flip-flopped third act that transforms the film from an unendurable exercise in brutality that only sick people could enjoy into something truly odd and therefore interesting. I don’t know who exactly this film was made for, but somehow it caught on and grossed more than thirty times its budget.

In between my aborted viewing attempt and the time that I made it the whole way through, I was exposed to the films of Ingmar Bergman. Craven’s films were made for a vastly different audience than Bergman’s, but the horror icon lists him as a prominent influence. The Last House on the Left lifts the plot of Bergman’s The Virgin Spring, translating it from medieval Sweden to hedonistic 1970s America. Two hippie teenagers, Mari (Sandra Peabody) and Phyllis (Lucy Grantham), squirm their way out from under the watchful eyes of Mari’s parents to attend a rock concert for Mari’s seventeenth birthday party. On their way into the city, they hear a news report of escaped convicts—Krug (David Hess), a rapist and serial killer; Junior (Marc Sheffler), his addict son; Weasel (Fred Lincoln), a child molester; and Sadie (Jeramie Rain), a shared girlfriend. Inevitably, when the kids arrive in town and try to score some marijuana for the concert, Junior lures them into the felons’ shared hotel room where they are kidnapped.

They are held overnight, and the next day they are taken into the woods where they are forced to perform terrible sexual acts with one another as well as the fiends. Phyllis tries to flee and is stabbed to death. Mari convinces Junior to help her escape but their plan is foiled by Krug, who carves his name into Mari’s chest, rapes her, and then shoots her as she stumbles into a nearby pond. The felons clean themselves up and make their way to the nearest house, posing as traveling salesmen. Coincidentally, the house happens to belong to Mari’s parents, Estelle (Eleanor Shaw) and John Collingwood (Richard Towers), who are welcoming to their guests but justifiably on edge about their missing daughter. The hosts soon discover that their visitors have killed their daughter when Estelle discovers that Junior is wearing Mari’s necklace. They verify her demise, then set about enacting their brutal revenge on the criminals.

I understand that the film is provocative for provocations’ sake—that its goal is to shock the viewer. It does this better than most films of the modern era that copy it, that think gore and nudity and backstabbing are sufficiently shocking in and of themselves, and so neglect building anything around the visual nastiness. It’s incredibly effective at making you feel the anguish of the two murdered girls, in part because of the young Craven’s charming clumsiness and his unknown casts’ lack of polish. At times, especially in the early going, the film does a very “good” impression of a snuff film.

Where I take issue, and where I feel that the film kind of falls apart as a horror film, is in how gleefully Mari’s parents enact revenge. In The Virgin Spring, Max von Sydow’s character hesitates to take the lives of his daughter’s killers, and prays for guidance and absolution. In The Last House on the Left, Mrs. Collingwood takes joy in seducing Weasel, tying him up in an episode of kinkiness, and then biting off his virile member as he reaches his climax. After the harrowing deaths of the girls, it’s impossible to seriously consider that a mother, having just discovered that her daughter was killed, would decide that it is a good idea to seduce and fellate her killer as part of her revenge plot. Mr. Collingwood similarly takes delight in rigging up some MacGyver-esque boobytraps and finally disemboweling Klug with a chainsaw. These deaths don’t feel like they belong to the same film as the gritty deaths of Mari and Phyllis—they’re so different in tone that they cause the film to lose the horrific tension it had built up in its first few acts. The film was not really funny at all before this section, but viewing it through a comedy lens is the only thing that works. Two clumsy cops (played by Marshall Anker and Martin Kove2) and absurdist cross-cuts also push us into this frame of mind. It’s not every day you see avert-your-gaze rape scenes intercut with slapstick; or girl’s being forced to undress at knifepoint juxtaposed with cake decorating.

Craven can’t stack up against Bergman, but he does a few things that I think are noteworthy. First, as was common for many filmmakers of his generation, he cut his teeth by just going out and making something with only a little money (I mean, the budget amounts to a cool half mil in today’s dollars, but still). I’m always a fan of that, mostly because I’m jealous of the audacity. He wasn’t expecting people to watch it, so scrutinizing the film’s shortcomings and questionable decisions is probably unfair because it’s only possible to critique it now against its reputation. Craven claims they didn’t get any permits and had to use a “guerilla style” of shooting—dropping in, getting their shots, and getting out quickly. Because the production was a first-time experiment for many involved, it is not obvious to me that the aims were clear from the outset. I think that if the filmmakers had realized how brutal and effective the opening of the film was, they may have opted for a less campy finale. They’d’ve definitely cut the silly cops. Maybe they didn’t realize that the amateur nature of the shoot, the low quality of the image, and the inexperience of the cast would all lend themselves to saturating the rape/murder section with a pervasive sense of dread. Whatever the case, the Manson family wannabes that Craven conjured up here are much scarier than Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers because the violence they enact feels completely real, and watching it is thus a harrowing experience—that makes the film less enjoyable than Friday the 13th and Halloween, but not any less effective.

And but so we’re left with this lumpy amalgam that is two parts diabolical to one part kitsch. Horror-comedy is a rich genre that is perfect for early-career filmmakers to pull off on a low budget, but usually those two elements are kept in tension throughout. The brand of humor is usually different too. You probably won’t laugh out loud at The Last House on the Left, but when it dips into the absurd and the surreal—e.g. when the girls are loaded into the trunk of a car and a cheery country-folk song begins playing with lyrics about the girls being kidnapped by Krug and his posse (the song was written and performed by Hess)—there’s no other way to comprehend these moments in a positive light than to read them as camp. Whether all of that was intentional or is actually enjoyable is up for debate. I’m lukewarm.

1. We’re married now—and we’ve settled on a general rule that I have to watch horror, gangster, black and white, foreign, Western, and arthouse movies by myself.

2. For many in my generation and the one before it, Kove is instantly recognizable as Sensei John Kreese from The Karate Kid and its sequels. It’s been nice to see him experience a bit of a late career renaissance, snagging a minor role in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and reprising his role as Kreese in the Youtube series Kobra Kai that has since been picked up by Netflix after its first few seasons.