“Luck is being a Vanderbilt or a Carnegie.”

Even the inimitable Marty Scorsese owes a debt of gratitude to schlockmeister and trailblazer of independent cinema Roger Corman. Everyone that hasn’t been living under a rock for the past fifty years has heard of Scorsese. But in the early 1970s he was just another movie brat with a single student film to his name (Who’s That Knocking at My Door) looking for a project to cut his teeth on. He’d been fired from the production of The Honeymoon Killers and found work editing the Woodstock documentary and working on sound design for Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz, as well as teaching at his alma mater NYU. Corman, ever the opportunist, was looking for someone to helm an exploitation film in the same vein as the titan’s own Bloody Mama, a surprise hit on the coattails of Bonnie and Clyde. And so, on the strength of Scoresese’s first feature, he was scooped up by Corman to direct Boxcar Bertha.

Corman had done similar with several other budding talents such as Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Monte Hellman, and Nicolas Roeg, providing a low pressure venue for them to get some reps in and sharpen their vision. Boxcar Bertha was double-billed at the drive-ins with 1,000 Convicts and a Woman, which clues us into the kind of film Corman was aiming for. He gave Scorsese $600k, twenty-four days of shooting in Arkansas, and a chance to rewrite the script to his liking—though he was adamant that the screenplay not go on for more than fifteen pages at a time without a fistfight, a shootout, a car chase, or a gratuitous sex scene. While the fingerprints of Scorsese’s burgeoning talent are evident, Boxcar Bertha is decidedly the pulpy exploitation film that Corman envisioned, albeit one that exceeds expectations.

Using Bonnie and Clyde as a template, Scorsese takes us into the Depression era South with an adaptation of Sister of the Road, a fictional memoir of the outlaw life that many believed was a true story at the time. The book was written by anarchist and physician Ben Reitman, AKA “King of the Hobos,” who offered his services to outcasts, prostitutes, and the impoverished, and later admitted that Bertha was an embellished amalgam of several women he met during his travels.

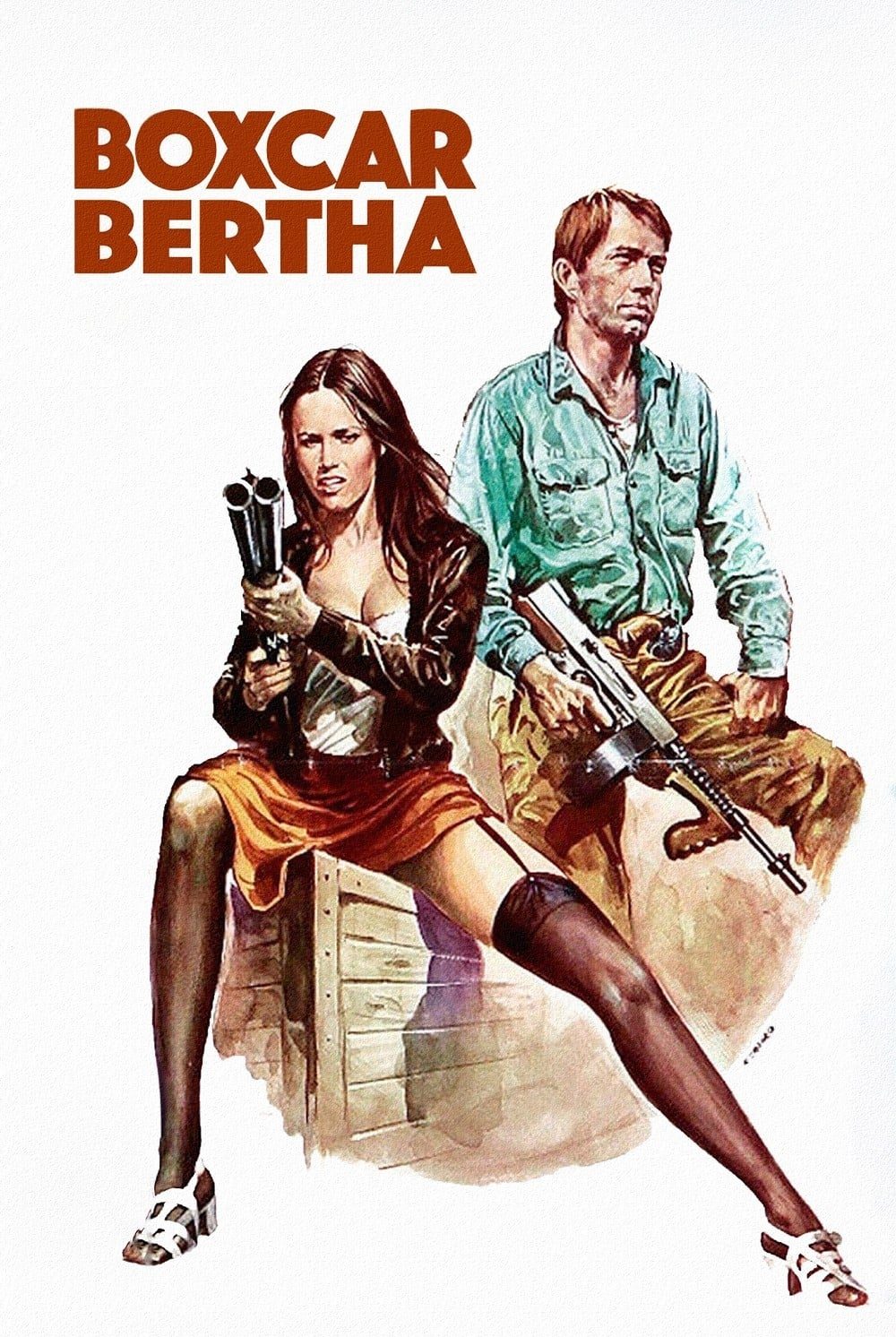

Raised in a world of hillbillies, cardsharps, and blues music, free-spirited Bertha Thompson (Barbara Hershey) trusts her fate to the railroads when her crop duster father dies in an airplane accident. After falling in love with a union organizer named Big Bill Shelly (David Carradine), Bertha and her man begin a criminal career, stirring up trouble on the railroad and earning a dishonest living. Their posse expands to include sidekicks Rake Brown (Barry Primus), a cowardly Yankee, and Von Morton (Bernie Casey), a shotgun-toting, harmonica-playing mechanic. They hop trains, rob railroad tycoons, cheat at gambling, spend time in prison, break out of prison, and work in a brothel—well, Bertha does, anyway. Their criminal rampage begins when Bertha shoots a crooked gambler who was about to plug Rake, and doesn’t end until a Big Bill is nailed to the side of a railroad car in imitation of the crucifixion.

It’s definitely fun, like any other exploitation film of its ilk, though Scorsese does not treat the violence as giddily as his contemporaries of the time. The expected detours into sexploitation and staged comedy go about as you’d expect, not totally derailing the proceedings but largely unnecessary. It gets by on the charm of its two leads and several solid supporting roles, along with Scorsese’s little flourishes in editing and lensing that inform you that you’re in capable hands, restrained as they are. One notable instance of the young director’s flair is when he cuts from Bertha’s scream to a similarly pitched harmonica at the opening credits. Later, when Bill is pegged to the side of the train, he mounts the camera on the train to show Bertha receding into the background while Bill remains stationary in the frame.

Unfortunately, due to its ramshackle nature and Scorsese’s inexperience, there’s little oomph here—just a gang of outlaws riding around, hopping freighters, and living on the outskirts of society. Hershey’s arc from naïve country girl to hardened, sexualized criminal is a solid central performance. Carradine is good too, and the baby-faced Scorsese cameo is a funny treat. Scorsese shows off in many small ways (there’s even a cool split diopter shot). But too often those nice touches feel like misguided embellishments on a schlocky story that favors nudity and blood over camera tricks and nuanced acting.

It’s an interesting mashup of Scorsese’s budding style and Corman’s typical exploitative thrills, but not the most exciting entry in either’s canon. At the very least, it’s a side trail to explore when moseying through the maestro’s filmography that gave him a chance to flex his muscles and narrow his focus toward the personal projects that have been his calling card ever since.