“I’d forgive you if you were crazy but you’re not. You’re weak.”

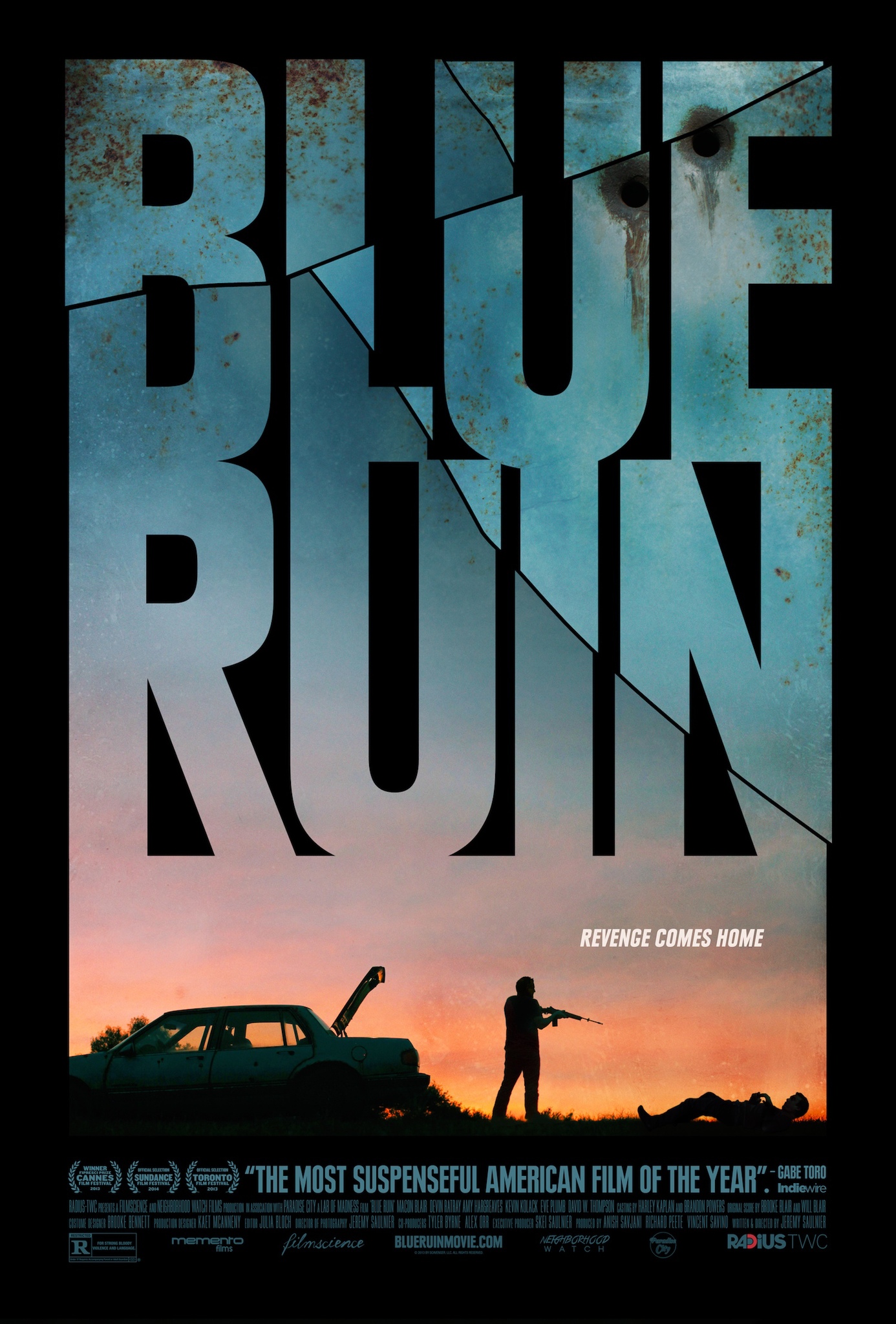

Conceived as a last hurrah for aspiring filmmaking buddies Jeremy Saulnier and Macon Blair, Blue Ruin is a shining example of the merits of crowdfunding and DIY audacity. With an intelligent script, a creative shooting style, and $35k raised on Kickstarter, the duo has crafted a revenge thriller that rivals its big budget studio analogs. Subtly inventive in many ways, this independent production is a testament to what can be achieved when filmmakers are forced to rely on pure craft for cinematic value. Written, directed, and shot by Saulnier, Blue Ruin is undoubtedly worthwhile for the aspiring filmmaker who wants to see the shoestring production in effect, but even those who tend toward a more generic cinematic diet will find little to complain about.

The most important element of the film is Macon Blair’s performance. We first meet Dwight (Blair) as a vagrant. He’s car camping on the beach, scrounging for food, and trespassing into the homes of the wealthy when he needs to clean up. Little exposition is required for us to glean the premise: haunted by his parents’ murder some twenty years ago, Dwight discovers that their killer is set to be released from prison.

The news flips a switch somewhere deep inside the wounded man’s psyche, immediately setting him on a course of action that will inevitably lead to bloodshed. Swapping in a new battery and gassing up his dilapidated car, Dwight follows a roadmap back to Virginia, heading in the direction of conflict without a plan of attack. He steals and discards a revolver with a trigger lock on it, then sneaks into the bar where Wade Cleland (Sandy Barnett) and his family are celebrating his release. In the bathroom, Dwight cowers in a stall, gripping a knife while Wade enjoys peeing alone for the first time in decades. When their eyes lock through a crack in the door, Dwight lunges out from the shadows. This swift vengeance is a shocker for the audience, who may have assumed this quest would take up the bulk of the movie; it also serves as a strong catalyst for the subsequent acts in which Dwight must face the consequences of his actions.

But then Blue Ruin shifts gears. For that initial bloody mission, Dwight was an inhuman force of nature, bedraggled and wild-eyed and unstoppable. Escaping the mini bloodbath by the skin of his teeth, he bandages himself up, shaves his unkempt beard, and trims his hair down to a respectable length. Now instead of a crazed homeless man, he looks like a blunderous, spineless cube dweller who couldn’t even open a bottle of Gatorade, let alone handle a weapon or kill a man in cold blood. His flabby jowls and shifty eyes color him as an amateur in over his head, not some hardened criminal. But the family he just pissed off, who did not inform the police that their brother had been slaughtered by a maniac with a carving knife in a public restroom—they’ve done this before. And suffice to say that Dwight misunderstood the situation and that Wade’s brothers and sisters do not believe that Dwight’s revenge was justified.

As Dwight frantically tries to protect his estranged sister and her family from retaliation, Blair infuses his character with an uncanny desperation that manages to endear him to the audience, even while he is committed to such an evil course of action. And this is not one of those stylistic revenge thrillers where you actively root for the deaths of the bad guys—the screenplay is much subtler than that, coloring in the black-and-white with many shades of grey. The script features minimal dialogue—Saulnier clings to the perennial advice of “show don’t tell”—but each verbal interaction is written with precision, economically packing character and backstory into these little moments. The small supporting cast tucked in around Blair are also excellent, from the vengeful, trigger-happy members of the Cleland family (Kevin Kolack, Brent Werzner, Eve Plumb, Stacy Rock) to Dwight’s sister (Amy Hargreaves) to Dwight’s high school buddy Ben (Devin Ratray). There are three conversational scenes that fill out the emotional core of the film. The first is between Dwight and his sister, when he reveals that he has killed Wade, then comes to the realization that their lives may be in danger because the murder was not reported on the news. The second is when Dwight requests help from Ben, an eccentric Army vet with extensive knowledge and enthusiasm for firearms. The third is when Dwight, shaky and unsure of himself, opens the trunk of his car to confront Teddy, and learns the true history of the feud between their two families.

Saulnier also does very solid, subtle work in fleshing out the world and making it feel larger than the blood feud at the center of his story. Early in the film, while Dwight is scrounging, he looks up and sees children on amusement park rides along the boardwalk. And just before he enters the bar to murder Wade he sees chemtrails streaked across the sky from the exhaust of a jet. Several humorous moments break up the otherwise stark proceedings, such as when Dwight is mid-confession with his sister and a diner at the table next to them asks to borrow their bottle of ketchup; or when Teddy springs from the trunk, where he’s been cooped up for hours, and snatches the rifle from Dwight, only to flail around because his legs are asleep. Beyond these wrinkles in the screenplay, Saulnier excels in wringing a high production value out of his limited budget. There are only a few instances of graphic violence, but they are brutally gory and will make your heart skip a beat or two.

A sleek thriller marked by complex characters and a creative, low-budget production, Blue Ruin refuses to find glory in vengeance. Macon Blair’s understated performance anchors a pleasantly unpredictable narrative in which the main players are morally neutral; you just want everyone to stand down and make peace though you know that’s an impossibility.