“People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between the past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

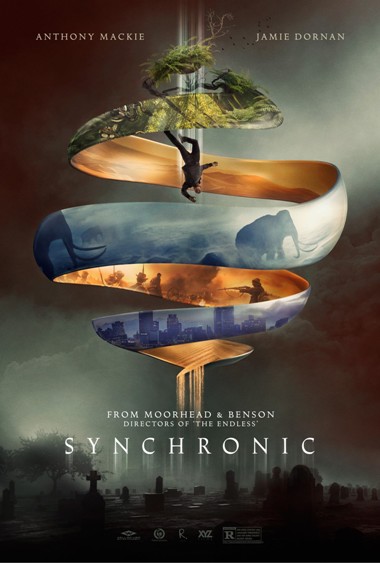

After years of toiling away on modest indie sci-fi/horror projects, Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead have finally dipped their toes into the waters of the mainstream, casting a Marvel Avenger in another of their mildly ambitious time-traveling films. Synchronic features Anthony Mackie as a lackadaisical, womanizing paramedic who begins experimenting with a synthetic drug that has been ravaging the doper community in his hometown, producing improbable wounds and mysterious artifacts. As we quickly learn, the little pill actually sends users back in time Billy Pilgrim style.

Though they’ve been hailed as fresh new voices in the realm of science fiction cinema, aside from their excellent debut, Benson and Moorhead have failed to impress me. Synchronic does not change my opinion of them, which is that they’ve carved out a niche by building lackluster stories around intriguing ideas. Since the raw and invigorating Resolution, with its grim sense of foreboding and climactic time-bending freakout, the filmmakers’ works have become increasingly dull, uninspired, and contrived. Synchronic is perhaps the most obviously inorganic of the bunch.

The film’s opening scene is its best, as two nameless addicts swallow Synchronic and suffer from reality-altering hallucinations, paralyzed with horror as a hotel room morphs into a dense forest; and freefalling from the sky toward the harsh dunes of a desert. When paramedic buddies Steve (Mackie) and Dennis (Jamie Dornan) nonchalantly respond to a series of 911 calls, they find a woman snakebitten by a species that hasn’t been in the area for decades, a destroyed corpse of a man who’s fallen down an elevator shaft, a burn victim charred to a crisp, and another body rapidly pumping blood out of a sword wound. This opening sequence has a pleasant weirdness to it as the two lifelong buddies casually respond to urgent cases and try to puzzle through the odd injuries to those who have taken Synchronic. Rather than jump right into time-traveling, it half-heartedly attempts to sketch out the life circumstances of the two leads in an unhurried manner, with the lacking script thankfully overcome by consummate acting from Mackie and Dornan.

When Steve accidentally sticks himself with a druggie’s used syringe, a test for various infections leads to a cancer diagnosis—the kind that gives a man “six weeks to sixty years” to live. The malignant tumor is growing in his underdeveloped pineal gland, the mystical “third eye” that typically calcifies as one grows older. Adults who take Synchronic move through time like ghosts, recalled to the present reality when the drug wears off after seven minutes. Young people, specifically Denny’s daughter Brianna (Ally Ioannides) and the young-at-pineal-gland Steve, traverse time more completely and can become stuck there if they do not follow some hazy time-travelling rules that Steve discovers through trial and error. When Brianna goes missing—presumably stuck in time—Steve takes it upon himself to buy up all the Synchronic on the market, experimentally determine the mechanics of time-travel, rescue his friend’s daughter from the clutches of the past, repair his uncertain relationship with his BFF, and prove to himself and those around him that “the present is a miracle, bruh.”

Once Steve starts his adhoc testing, the entire horror/mystery vibe is dropped in favor of a time travel lark that looks fun on paper but is played entirely straight. Steve buys out the supply of Synchronic at a local drug store, has a contentious confrontation with the drug’s creator, and begins videotaping himself jumping through time. His first trip takes him to a swamp where he is attacked by an alligator and a conquistador. He then experiences the ice age, gets chased up a tree, loses his dog in the past, and encounters a tribe worshiping around a campfire. His experiments teach him that the drug takes the user back in time to the exact physical location where it is taken, and that the precise coordinates of that location determine what time period one is transported to (I didn’t realize New Orleans had such a diverse history with all the flooding, conquistadors, KKK members, deserts, dense forests, etc.). In an incredibly hamfisted finale, Steve, a black man, travels back to a segregated Louisiana where he becomes trapped in order that Brianna may return to the present with the last dose of Synchronic.

The most glaring issue here is that Benson, who is the primary writer, doesn’t seem to care too terribly much for consistency, cohesion, or plausibility. Each little background decision seems overbearingly calibrated to usher us toward the unnecessarily cheesy conclusion. There’s a limited supply of the drug so that Steve cannot save both himself and Brianna at the end; Dennis has an old pineal gland so he can’t save his own daughter; each trip to the past results in immediate, open conflict with a person from that time. Even the particulars of time travel seem tailored to trap Steve in the past where people with his skin color were not treated well (the film’s conception of time suggests that we should have seen some forward time travel during Steve’s trial and error, but we do not). It makes sense knowing that Steve is literally dying and has the ability to time travel for him to willingly sacrifice himself for his best friend’s daughter. But the buildup to that manufactured moment feels entirely phony. All that sci-fi mumbo jumbo to trap a black man in the Jim Crow era South? The initial surreal sci-fi idea holds such promise. For the potentially abstract mystery to fold in on itself and be ushered into such a lame ending is a letdown. If we back up for a moment, it becomes clear that none of this is organically connected. The racial overtones are entirely separate from the brain cancer or the failing marriage; and too little time is spent linking them to adequately disguise the artifice. By the time Steve’s spectral form shakes Denny’s hand in wistful farewell, the shortcuts to emotional depth and questionable decision-making don’t allow for a satisfying conclusion, as awe-inspiring as the moment seems in a vacuum.

Synchronic is Benson and Moorhead’s largest production to date, but in swinging for the fences and missing, it may also be their weakest. It’s clear that they know what big, beautiful, heartfelt moments look like, and they capably supply them, wrapped in a neat sci-fi package. But too often they veer into the weeds in one way or another and then, without correcting course, just pack up and teleport us right to the destination they were previously aiming at. That’s going to ring hollow every time, and any emotional drama they were trying to wring out of the contrived storyline falls flat because it has not been earned.