“The Day of Judgement is at hand. Have mercy on my soul… and to Hell with all the others, amen!”

Robert Wise’s 1971 film, The Andromeda Strain, presents an interesting scenario—a satellite returning to earth containing microbial life from outer space. The film is adapted from the book by Michael Crichton, who would soon become a filmmaker himself as well as pen the famous Jurassic Park and its sequels. The film’s biohazard plot begins when a satellite crash lands in Piedmont, New Mexico, and nearly all of the town’s residents appear to die almost immediately—except a newborn baby and an old man. A state of emergency is declared, and a contingent team of experts descend below the surface of the earth into an isolated lab to study the satellite and the survivors.

Through flashbacks we see Doctor Jeremy Stone (Arthur Hill) petition the government to construct a secure underground laboratory to handle a situation where an alien life form is brought to earth on a returning spacecraft; the secret lab, codename Wildfire, is situated five stories below ground in Nevada. Flashforwards show the breakdown in communications between the officials on the surface and the scientists isolated in the lab. An interesting dynamic occurs, contrasting the dire situation aboveground with the tedious, methodical proceedings of the scientists who believe they are studying the organism in isolation.

Dr. Stone was adamant that the US President authorize dropping nuclear bombs on the town of Piedmont to obliterate any chance of the spread of the disease, but the command was delayed. When Stone and fellow scientist Dr. Leavitt (Kate Reid) locate the crystalline lifeform—roughly the size of a grain of sand, seen clearly only under 1000x magnification—they discover that it can continue multiplying itself even in a vacuum. Amplifying the tension is Crichton’s Odd Man Hypothesis, a statistical analysis that determines who is the least likely to shut down the automatic nuclear destruction of the Wildfire lab that will occur if the containment of the lifeform is compromised. This responsibility rests in the hands of Dr. Hall (James Olson), a single male. The scenario is subverted when the scientists discover that the organism absorbs energy and uses it to grow, and thus a nuclear explosion would be catastrophic for humanity.

Charles Dutton (David Wayne) rounds out the team of experts, while Karen Anson (Paula Kelly) portrays a nurse and laboratory technician who cares for the survivors. Following Crichton’s novel closely (though in the novel, the epileptic Leavitt is male), the character’s actions are methodical, and their frustrations genuine as they repeatedly fail to find a solution and gradually exhaust their vast professional knowledge. As their ideas are presented, tested, and deemed incorrect, they grow evermore frenzied and argumentative with one another, each believing they are on the right track to solving the mystery.

The film handles its science well. Crichton, who wrote the book while in medical school, claims to have done minimal research for the novel, as he simply wrote about the subjects he had learned. They utilize electron microscopes and growth cultures to analyze and study the lifeform, and Dr. Hall interviews the patients to try to discover what they have in common that led to their survival.

The team also does tests on animals, which results in several disturbing scenes as the animals seem to be in great pain as they die. Although the film claims no animals were harmed in the credits, in order to portray the Rhesus monkey dying realistically, the filmmakers subjected it to carbon dioxide, and immediately administered oxygen to it when it passed out. There are several other elements which make the film’s G rating questionable. As Stone and Hall first survey the town of Piedmont, there are numerous shots of gruesome death. Bodies of deceased children, an old woman hanging from a noose, a man that had drowned himself in a bathtub, and even a nude female torso. The film was released before the implementation of the PG-13 rating, but the GP rating (analogous to PG today) was available; that would have been a much more suitable choice for a film with such grisly images (though it would likely receive PG-13 if released today).

Additionally, at times the film veers into a camp aesthetic, and I believe this is intentional. As the automated system requests the scientists state their names (surname first) Dr. Hall smirks as he states, “Hall, Mark.” He flirts with the bodiless voice, and is chastised over the intercom by a supervisor. “Sorry, her voice is quite luscious,” says Hall. “The voice belongs to Miss Gladys Stevens, who is 63 years old. She lives in Omaha and makes her living taping messages for voice reminder systems,” the supervisor replies. “Much obliged,” says Hall. Partway through the film, when Stone asks the clerk if any communications had come in (communications are not coming in at all, remember), the clerk launches into a tangent that is completely out of line considering the ominous situation. “Dr. Stone, sir. I have one thing to do. Just one. Everything else is fully automatic, computerized and self-regulated. I listen for a little bell, in here. ‘Ding-a-ling!’ That means a message coming in that’s for the Wildfire team. […] Top priority. ‘Ding-a-ling!’ I push a button, and all five level control centers are notified the same time you are. The bell hasn’t rung, sir.” We even get a proto Daft Punk sighting as the epithelial layers of the scientists’ skin is burned away.

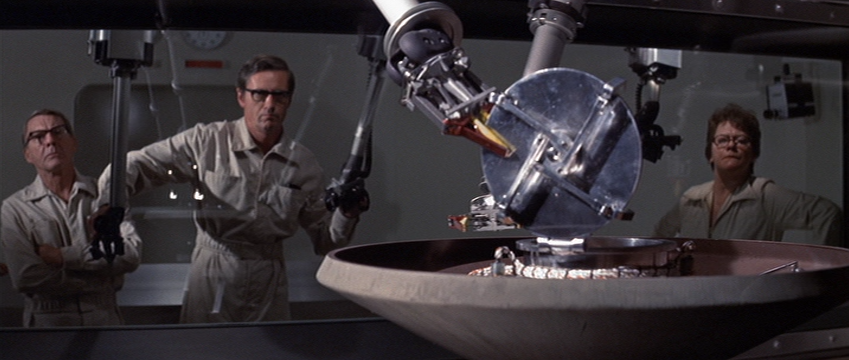

While the effects appear dated, especially when compared with its most obviously comparable contemporary—Kubrick’s exquisite 2001: A Space Odyssey—it is worth noting that though the film is science-fiction, it is set in the era it was made. In other words, its only contrivance is the presence of the microorganism. The scientific components, propped up by Crichton’s own doctoral studies, are robust and make use of what was known at the time; so the dated technology—rudimentary electronic displays, computer-controlled cameras, photographically capturing the image of a microscope, bare-bones robotic arms, etc.—should look dated as they are not meant to predict future technologies. It is only when a film is set in the future that is runs into problems. That is why the longevity of many sci-fi films suffers, and why films such as Spielberg’s Minority Report are such a rarity, in their careful consideration of the trajectory of technological advancement. The film’s main set is actually quite elegant; the sterile pathways and laboratories of the labyrinthine Wildfire compound appear state of the art. There’s even a 3D projection of the underground bunker that was achieved practically but looks like a dated computer rendering. And I can’t forget to mention the sneaky double split diopter shot that occurs early in the film!

The film’s scope and creative direction are also of note. Along with the scenes detailing the appeal by Stone to create the lab, and the flashforward investigating the communications failure, peppered throughout are scenes outside of the laboratory—military personnel discovering a crashed plane due to the dissolution of gasketing material, conversations with the President’s aide, and each team member being summoned from their home or place of work. As the scientists sleep, split screen and storyboard effects allow us a glimpse of their dreams and their personal attachments to the subject matter. The same effect is used when Stone and Hall search a building in Piedmont, as a handful of images of dead bodies are flashed on the screen while at the same time we see Stone and Hall peeking into doors and windows.

The film does suffer a bit from overly workmanlike acting from the principal cast—Kate Reid and Paula Kelly imbue the plot-heavy narrative with much of its vibrancy—and its palatability would be improved if the runtime were trimmed by 10-15%. Robert Wise, editor of Citizen Kane and director of The Sound of Music may have seemed an odd choice for director but for his 1950s black-and-white sci-fi film The Day the Earth Stood Still, and he would dust off his sci-fi hat again for 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The film’s premise—a potentially lethal biohazard in a secret lab escaping its containment—was influential, most notably on the Resident Evil franchise of video games and films which would come several decades later, but also seen in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (also based on a Crichton novel) and Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later. The creative direction and intricate plot, mixed with the tongue-in-cheek hamminess and grounded scientific research result in an enjoyable if dated science fiction film.

Sources:

Anders, Charlie Jane. “True Stories of Animal Actors in Science Fiction and Fantasy Movies.” Gizmodo. 1 July 2011.