“Any conversation is a unique jazz performance. Some are more pleasing to the ears, but that is not necessarily a measurement of their importance.”

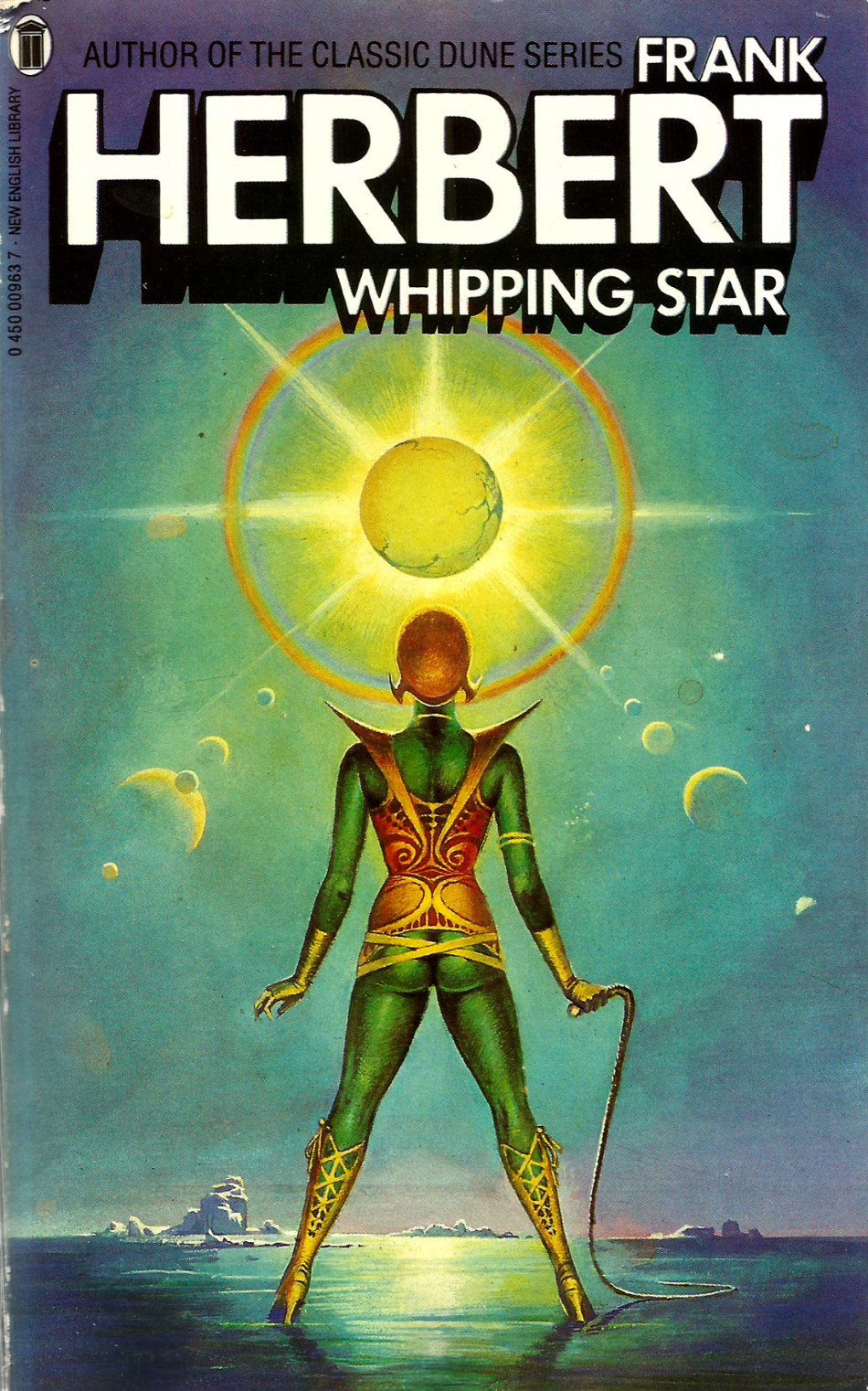

The Dune novels are bedrock science fiction. For most, including myself until about a week ago, they are the only works of Frank Herbert that ever make it to the top of the queue. Heck, many readers jump ship when he reins in the action and turns philosophical, stalling out before even finishing the series. Anyway, Herbert was responsible for creating two additional sci-fi worlds. The ConSentiency universe was initially sketched out in two short stories beginning in the 1950s (both stories can be found in Eye). It’s in these early tales that we first meet the character of Jorj X. McKie, an agent of the Bureau of Sabotage who serves as the protagonist of Whipping Star.

Now, it must be acknowledged at the outset that it is futile to compare Whipping Star to Dune. Don’t come here looking for sophistication, piercing vision, and intergalactic politics; or a sociological and ecological transformation backed by far-future mythologies based on ancient traditions. That would be a mistake. To recalibrate expectations, think Philip K. Dick doing Mad Libs on acid. That should bring to mind the bulk of PKD’s oeuvre, which puts us in the right ballpark.

So let’s set the stage—Mliss Abnethe, a sadistic octogenarian whose countless cosmetic surgeries have transformed her into a curious combination of attractive and repulsive, has been conditioned to have zero tolerance toward the witnessing of pain. To get her rocks off she has entered into a contract with a Caleban—a godlike alien that lives inside what is described as a giant beach ball and appears almost immaterial to human perceptions, and can also teleport humans anywhere instantaneously. In exchange for knowledge of humanity, Fannie Mae (the Caleban)—who shows no physical signs of its distress and thus skirts Mliss’s conditioning—allows herself to be whipped for Mliss’s pleasure. She will soon die from the attacks, and when she does any creature that utilized a Caleban jumpdoor will die with her. Meaning the vast majority of sentient creatures, be they Human, Gowachin, Laclac, Wreave, Pan Spechi, or Taprisiot, will perish instantaneously.

In this far-future world in which humankind has made friendly contact with so many other species, the intergalactic political machine quickly got out of control. Laws were being speedily passed without thought to their downrange effects. To combat this, the Bureau of Sabotage (AKA BuSab) was launched to put dampers on government overreach and mitigate the effects of reckless legislation. BuSab agents, among them the observant Jorj X. McKie, are allowed to harass any government org in the ConSentiency, but private citizens and vital societal functions must remain undisturbed. McKie’s been assigned to make meaningful contact with Fannie Mae, who has washed up injured on a coastal rock formation, and save countless lives in the process.

Whipping Star is shameless pulp with only half-hearted attempts at the depth Herbert achieved elsewhere. What contemplation does occur, on the futility of communication, the nature of reality, the cons of bureaucracy, the energy of creative activity—all interesting topics—are just poked at and feel shallow when presented alongside such an unabashedly lowbrow story. And the scale is off too. Set in an unfathomably vast universe in which entire planets are dedicated to specific activities and unfamiliar species abound and the fate of all sentient life is on the line, the plotting is too cartoonish for the necessary narrative gravity to ever materialize.

The most successful aspect is the impossible communications between McKie and Fannie Mae. The Caleban doesn’t experience reality the same way that we do, and so they consistently talk past each other, misunderstand emphases, require new definitions of common words, veer off course on semantics. At one point she teleports an agent to the place where he was born when he requested to be sent “home.” She refers to death as “ultimate discontinuity.” The mind of the Caleban is so impenetrable to those of any other sentient creature that the motives and functions of the beach ball aliens are complete mysteries. It’s the human language barrier multiplied a thousandfold. An interesting puzzle, but one that ultimately gets lost in some gimcrack Alan Watts-esque mysticism veiled within the language of quantum physics.

I also thought that the Bureau of Sabotage was underutilized; or perhaps misutilized, as it didn’t seem to be slowing the government at all, but rather acting as a standard investigative agency. In theory, BuSab seems like the kind of thing that would crop up in a Heinlein novel and be used for a fun critique of our current power structures. Although cartoonish, Whipping Star is not exactly funny. There’s an undertone of absurdist humor that seems only half intentional and doesn’t always work. The only time I cracked a smile was when it was revealed that Herbert had named the Caleban after a government-sponsored mortgage company.

Frank Herbert was clearly brimming with interesting ideas. The difficulty of communicating with another sentient species is an interesting one but not comparable to the heady brew present in the Dune novels. Commensurately, Whipping Star is not very long. Setting aside the main ideas Herbert wants to explore, he doesn’t seem very interested in fleshing out anything more than a ramshackle frame story with stock villains and a telegraphed ending. As a speedy exercise between his weightier tomes it works well enough, but it’s a decidedly lesser effort.