“Most people don’t know how they’re going to feel from one minute to the next. But a dope fiend has a pretty good idea. All you gotta do is look at the labels on the little bottles.”

I find it darkly amusing that James Fogle was incarcerated when Gus Van Sant’s film adaptation of Drugstore Cowboy hit theaters. I find it deeply sad that, like the main character of his unpublished novel, he blew every chance he had to correct course. According to an L.A. Times obituary, he was rarely out of prison for more than a year and died behind bars while serving a fifteen year sentence for ripping off a pharmacy in his old age. “I always went back to what I knew,” he said. Like William S. Burroughs (who appears here briefly as an addict priest in rehab), his writing was intricately tangled with his own experiences, his harrowing life story lending authenticity to his absurdist tale of four transient dope fiends.

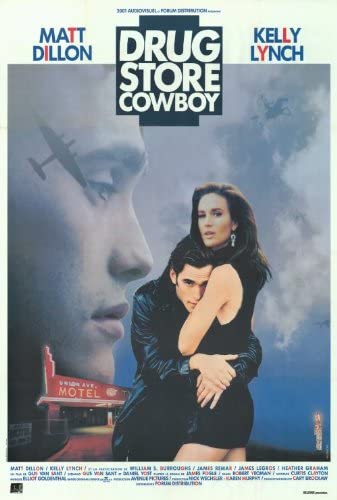

Set in Portland in 1971, Van Sant’s film immediately arrests the audience with a bold stylistic commitment that attempts to convey the life of the junkie. Using voiceover narration, elliptical storytelling, hallucinatory sequences, home-video, and jarring close-ups, we quickly come to understand the perpetually edgy mental state of Bobby Hughes (Matt Dillon). Along with his wife Dianne (Kelly Lynch) and a younger couple, Rick (James LeGros) and Nadine (Heather Graham), Bobby bounces around squalid motels and apartments in a constant state of superstitious fear, living hand-to-mouth and always looking for the next opportunity to score. In an early scene we see the group enact their scam. They each enter the store separately, create a commotion with a fake seizure, and then Bob sneaks behind the counter for the goods. Bobby is the only thief—everyone else is part of the distraction—and it’s Bobby who is so ecstatic with the haul that he shoots up in the getaway car and experiences the first of several laughably juvenile dream fantasies. In between robberies, the gang falls into a lazy routine of selling off their excess, getting high, chatting, watching television, and whiling away the days. Occasionally their fun and games are interrupted by a boorish cop named Gentry (James Remar) who enlightens us to the gang’s bush league criminal notoriety.

There’s a listlessness that goes along with the binges, but Bobby’s mind never stops for long. He’s a genius compared to the rest of the gang which makes him the leader by default. And for him, the thrill of planning a hit, the adrenaline rush of ripping through pharmacy drawers, and the elation of cataloguing his loot are more invigorating than just about anything—even sex. He plans and schemes with myopic focus even while he’s guided by an implacable logic warped by the needs of his habit. He earnestly follows his flawed convictions, though, and when the violation of his superstitious “no hats on the beds” rule leads to Nadine’s death, he follows through on a panicked vow to “God, Satan, or whatever is up there” to get clean. For a time, anyway.

I knew it in my heart. You can buck the system but you can’t buck the dark forces that lie hidden beneath the surface. The ones some people call superstitions.

Van Sant makes several crucial decisions that allow his film to land with great poignance. He does not portray his characters as bad, simply sick. There is no judgement of the lifestyle in either the narrative or the presentation. In fact, by introducing us to the quartet with a cheery home video he immediately creates charming characters out of a stock that would usually be considered abhorrent. It also helps that Dillon, Lynch, and Graham never look like anything less than beautiful movie stars (aside from when Graham becomes a corpse, of course). But then neither does he glamorize his subjects. The biggest triumph our protagonist experiences is a short-lived stint in rehab. And when he visits his mother (Grace Zabriskie) and the film briefly drifts outside of his own storytelling frame we are painfully reminded that addiction can absolutely wreck a family.

Oddly enough, then, a strong emotional connection is fostered by the group’s nuclear family dynamics. Bobby and Dianne were high school sweethearts and got married somewhere along their path to addiction. They’re veterans of the junkie lifestyle and basically function as parents to the younger Rick and Nadine. It’s the deep ties between the characters and Dillon’s sheepish charisma that allow some of the film’s zanier moments to work. There’s a scene in which Bobby tricks a pair of surveillance cops into suspecting his neighbor is holding his drugs for him. He then tells the neighbor there’s been a peeping tom looking through his window the past couple nights. The neighbor has a shotgun—you do the math. Bobby’s muted celebration from his second story apartment window is perfect. Later, when Nadine overdoses on Dilaudid and stops breathing and turns blue, Bobby is notified that they must vacate their room that very day because the motel is hosting a sheriff’s convention. There’s also hilarious flashback interlude where Bobby explains why they cannot discuss dogs, let alone have one.

And then there’s the matter of Burrough’s cameo. He appears at the rehab facility as a defrocked priest, delivering nuggets of druggie wisdom lent weight by his deep wrinkles, ragged cough and knowing smirk. It’s slightly distracting if you know who he is, but he serves as a legitimate cautionary tale for Bobby and possibly the audience as he articulates his worldview.

Narcotics have been systematically scapegoated and demonized. The idea that anyone can use drugs and escape a horrible fate is anathema to these idiots. I predict in the near future right-wingers will use drug hysteria as a pretext to set up an international police apparatus.

Drugstore Cowboy succeeds by diving into the dead-end perspective of its subjects and emphasizing the repetitive cycle of addiction. Like the work of Burrough’s himself, it has a randomly juxtaposed texture, as if the absurd situations our characters experience were pulled out of a hat and pasted together. But between each high comes a crashing wave of panic, a pang of guilt, and a fresh desire. Through the repetition a certain grimy poeticism emerges.