“I have decided to send the feminists, who have always ruined my life, to their Maker. For seven years life has brought me no joy and being totally blasé, I have decided to put an end to those viragos.”

Many blockbuster films take the kernel of a true story and build a Hollywood-sized spectacle around it, embellishing the truth for the sake of entertainment. Others strive for historical accuracy and go to great lengths to ensure the “facts” are represented correctly. But no matter the end goal of the production—whether it skews in favor of accuracy or entertainment—a million small decisions during the creative process permanently nail down a fictional version of the events in question. The sets can be recreated faithfully and the dialogue repeated verbatim from primary sources, but that still leaves plenty of hacking and trimming to fit a real-life event into a feature length film. And so the importance of the account’s veracity is debatable because it’s fiction either way. Adhere to the truth as closely as you want, it’s still fake, right?

I’ve long been fascinated by Baudrillard’s idea that cinema transforms history from myth into data; that it fixes the scattered details of an event, an era, a movement, what have you, into an “objective” form that replaces the actual thing. Learning about the Titanic or the Battle of Gettysburg or the Alamo is as easy as watching a Hollywood movie. These films are not documentaries—a medium with its own drawbacks when it comes to truth telling—but they use their truth claims to gain an audience and so must bear responsibility for presenting an accurate account. Case in point is Denis Villeneuve’s Polytechnique, a film that attempts to recreate the Montreal massacre but takes several intriguing creative liberties in the process. On the one hand, Villeneuve has committed himself to a true recreation of the events by unflinchingly placing us in the midst of the conflict. He doesn’t add to the body count or embellish the killer’s rushed suicide note with theatrical language. But he also makes a number of choices, both subtle and conspicuous, that shift our focus.

For those unfamiliar with the events in question (as I was upon clicking the play button): in 1989, Marc Lépine marched onto the École Polytechnique de Montréal campus with a Ruger Mini-14 and a hunting knife and shot 28 people, killing 14 of them—all of whom were women. He intentionally targeted the women, considering any female engineering student to be a radical feminist (his perceived enemy) and blaming their activism for his own failures as a man. I wasn’t alive at the time of the massacre, but after watching the film I searched online and found ample coverage from the news and academia, much of it predating the film. This plethora of coverage understandably calls into question the need for a feature film that may be perceived as exploiting a tragedy—intentionally or not.

Let’s consider some of the production decisions that obscure history and subvert our expectations. I think many of the choices stem from a conscious desire to deny Marc Lépine the notoriety he seemed to crave and shift that attention onto the traumatized survivors. All of the names are changed out of respect for the victims and to allow several characters to morph into composites, but the Lépine character (portrayed by Maxim Gaudette) is simply called “The Killer” in the credits. By shooting in black and white, lensing the victims’ bodies out of focus, and refusing to sensationalize the event through archival news coverage, Villeneuve softens the bountiful carnage and steers clear of exploiting the heinous crime. Presented non-chronologically, the film begins with the initial moments of the crime, then jumps back, leaps ahead, and returns to the chaos, etc. In the early going the focus is on The Killer, with a ~verbatim recitation of his suicide note conveying his bleak worldview. But very quickly Villeneuve immerses us in the lives of two others—classmates Valérie (Karine Vanasse) and Jean-François (Sébastien Huberdeau). In this way, Villeneuve deftly portrays the brutality of the crime and positions himself to explore beyond the immediate moment.

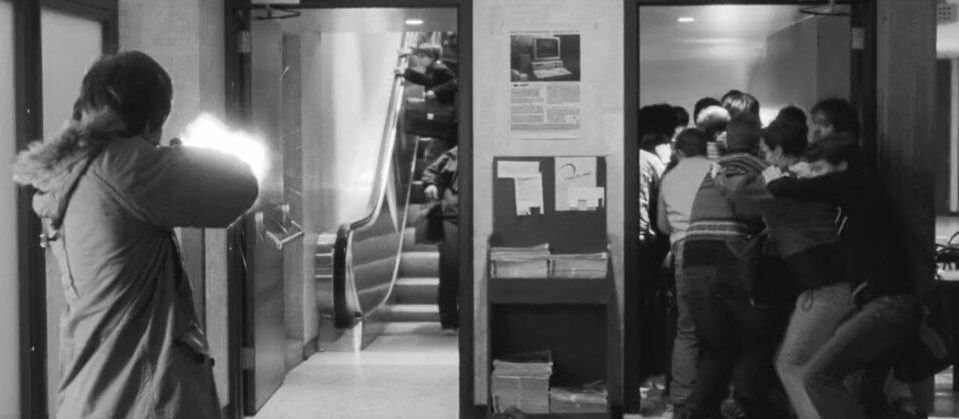

Valérie and Jean-François are in the same class when The Killer barges into the room, fires a shot into the ceiling, and demands that the women and men separate themselves. Corralling the men into the hallway, he turns his attention to the women huddled together in the back of the classroom and starts to ridicule them for their feminism. When one of the women meekly speaks up to say that none of them are feminists, he begins firing into the mass of bodies. The massacre is portrayed more or less in real time, though separated by the out-of-sequence editing. We return to the chaotic situation to see Jean-François fruitlessly aid the dying while Valérie, shot through the leg, limps her way to a lobby and encounters the murderer again. There’s a gut-wrenching scene where Jean-François comes back to the classroom and Valérie and another student (Evelyne Brochu) play dead because they think he is The Killer. He assumes they are dead and wanders off in a daze. In another scene, Jean-François wanders into a room of unwitting students partying to rock music—a brilliant illustration that the outside world can never truly absorb a tragedy the way an eye-witness can.

In the future sequences, the harrowing event has impacted these two students in very different ways. As composites, they serve as stand-ins for the genders—Jean-François representing the guilt of the men who were spared but powerless to prevent harm; Valérie representing the sharpened drive of the women who survived and followed through on their ambitions. As the film expands, so does Villeneuve’s artistry. In J-F’s case, his post-traumatic stress is expressed through lackadaisical pacing, a subdued tone, and a lack of engagement. He’s perpetually haunted by this past event and, tragically, decides to take his own life. Valérie has overcome her trauma but it has nonetheless shaped who she is, evident in an emotional phone call and an unexpected letter that she writes upon learning she is pregnant. Throughout, the camera is frequently utilized to emphasize turbulence, no instance more obvious than the concluding shot when the camera races down the school hallway with the frame flipped along its vertical axis.

In the end, Polytechnique is clearly ahistorical. Countless decisions, both conscious and subconscious, shape the work into a product that meets the expectations of the medium of narrative film. In contrast to the dry recitation of a coroner’s report or a newspaper article, the responsibility of the filmmaker is to bring the past to life before our eyes. Villeneuve achieves this, but it’s an inherently flawed process that cannot possibly claim to convey the whole truth. Instead, it offers a discourse that traditional media coverage of tragedy does not. I intentionally avoid the clickbait news sources, which means when I do happen to catch a breaking story I am all the more disturbed by the commodification of violent crime. With Polytechnique, Villeneuve uses art to explore beyond the realms of politically correct newscast language and psychological jargon, and by this virtue critiques traditional media’s propensity for making tragedy a consumer product. Villeneuve’s achievement, then, isn’t in how accurately he portrays history, but in how adeptly he spurs us to contemplation of his subject.