“Unless you’re sick or in trouble, you don’t even know I’m alive.”

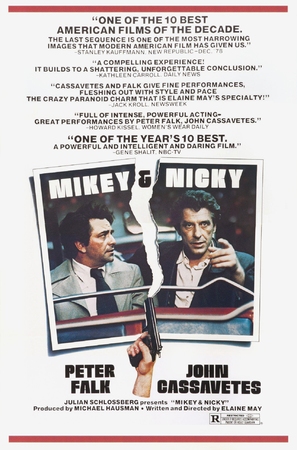

Multitalented and ambitious, Elaine May has achieved success in various fields of entertainment. From her early days in improv comedy with Mike Nichols, to acting on stage and in film, to writing scripts, her name on a project is a good rule of thumb for quality. This extends to her directorial efforts, which have sadly drifted into obscurity and do not enjoy the same recognition as her other work, largely because she was notorious for tumultuous productions when sitting in the director’s chair. Her first film, A New Leaf, a black comedy starring Walter Matthau, went over budget, causing the studio to step in and release a whittled down version that was nevertheless warmly received. Her second, The Heartbreak Kid, was another mild success and poised May for a career of offbeat romantic comedies. But then she tried to make Mikey and Nicky, a production which went 200% over budget and missed its delivery date. May was fired, then rehired when she refused to reveal where she had hidden several reels of negative. To spite her, Paramount released a butchered version of the film for a few days around Christmastime and then pulled it. Eventually, May and a few others would purchase the rights and recut it, prompting some limited reassessment, but the damage had been done. She would direct only one more feature (after a decade-long hiatus), and it took a Criterion release several decades later to see the reputation of Mikey and Nicky truly rehabilitated.

Mikey and Nicky was a deeply personal work for May, based on her own experiences and secondhand stories she heard growing up in Philadelphia in a mafia-adjacent family. One story in particular, that of a low-level gangster setting up a hit on his best friend, stuck with her through the years and became the basis for her free-spirited buddy comedy crime drama.

Peter Falk and John Cassavetes star as Mikey and Nicky, respectively, and the latter’s broad influence as an acting coach and filmmaker informs the production’s loose style and improvisational texture. In a way, Mikey and Nicky is a typical Cassavetes’ film with all its smoking, drinking, arguing and intimate character examination, overlaid with May’s trademark wit. But it’s very hard to pin down (which, in conjunction with Paramount’s lack of support, might account for its obscurity). It’s truly funny, especially in the early going, but it’s not committed to its comedy and seldom evokes laughter. It’s not much of a gangster movie, either. At least not the kind of glamorous crime flick popularized by Scorsese and Coppola. Rather, it depicts the lowest of the low in the world of crime—the small-time, fringe middle class nobodies who are discarded like pawns when it suits the needs of the bosses. But they’re incredibly layered individuals and it’s the peeling back of those layers, and the resulting horror, disgust, empathy, and pity evoked in the viewer, that differentiates Mikey and Nicky from its topical peers.

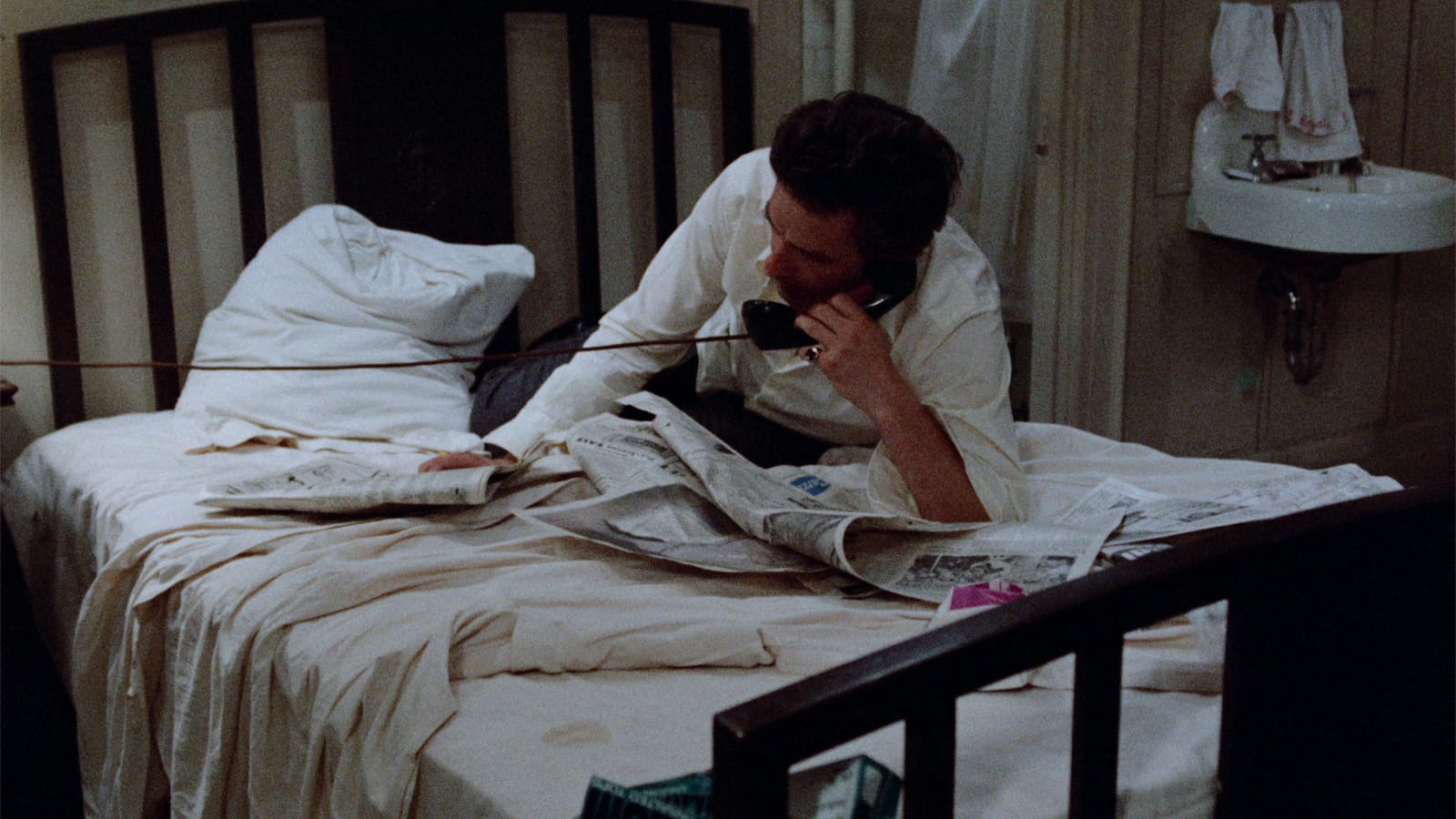

Taking place over the course of a single eventful night, the film begins with the paranoiac Nicky locked in a seedy little hotel room, smoking relentlessly and handling a small revolver. He has stupidly ripped off his boss (Sanford Meisner) for a paltry sum and now fears for his life, doubly so because his partner in crime has already been offed. In his panicked state he calls on his old friend Mikey, a fellow goon perhaps a link or two up the criminal foodchain, who begrudgingly arrives to help out his childhood pal. But even though he called and asked specifically for his help, Nicky doesn’t trust Mikey when he arrives. In vintage May fashion, Mikey talks his way into the room only to find his hysterical friend suffering from an ulcer. Given a ten minute time limit by Nicky, he sprints to an all-night diner, where he engages in an absurd negotiation with the counterman who appears unwilling to give him cream unless he purchases a coffee with cream in it. “Charge me for fifteen coffees and give me a carton of cream,” he says, before leaping over the counter and physically assaulting the man. When he finally returns to Nicky’s room, he must persuade the paranoid man to let him inside all over again.

Even as Mikey patiently cajoles Nicky into going with him to a nearby bar, the deep ties between them become readily apparent. And as the night goes on their bond is explored further, the camaraderie born from long familiarity contrasted with less rosy feelings that May brings into the spotlight through conversation and observational humor as she explores the divide between two old pals driven apart by a harsh occupation.

Almost as soon as the pair arrive at the bar, Mikey finds a phone booth to inform the hitman (Ned Beatty) of their location, and yet, as the night unfolds and the scatterbrained Nicky continuously evades the hit by dragging Mikey all over the city—to his mother’s grave, the movie theater, another bar, a prostitute’s apartment, his wife’s apartment—Mikey’s promises to help Nicky escape, even to run away with him, appear entirely genuine. Almost as if, were Nicky to only grant Mikey the genuine friendship and respect he’s always wanted, that Mikey may change his mind and help him get away. But of course the conversation cannot be had out in the open, lest Mikey recoil at an accusation and Nicky lose his sole ally. And so this poignant negotiation occurs below the surface with conversational hints and acts of empty machismo. It’s a beautifully tragic depiction of betrayal.

May intersperses the hills-and-valleys relationship of Mikey and Nicky with episodes that illustrate their flaws. The most prominent of these are an uncomfortable scene in which Nicky brazenly enters a bar full of black patrons and tries to pick up another man’s girl; and another where he forces himself upon his girlfriend Nellie (Carol Grace) and then invites Mikey to offer her a few bucks for a screw. Nicky is separated from his wife, who has taken their baby with her and seemingly does not care that Nicky has gotten himself into a deadly situation. Mikey’s family life initially stands in stark contrast to that of Nicky, but we soon realize that he is using calls to his wife (Rose Arrick) as cover for orchestrating the hit on his friend. But as the brutal finale unfolds on the doorstep of his house, he and his wife barricading the door to keep Nicky outside while Kinney (Beatty) blasts holes in their front door and Nicky’s chest, we realize that Nicky was closer to Mikey than his wife has ever been. It’s a powerful moment of irredeemable hopelessness and despair.

May reportedly shot over a million feet of footage for Mikey and Nicky, whittling down the scripted sequence and inspired improvisational moments into a loose but coherent collection of character observations. The continuity errors abound to such a degree that they cease to be a problem and render as an intentional effect of style, the juxtaposition of manic and calm takes and mismatched props almost emphasizing the love-hate nature of the central relationship. As they bumble about the city, uncovering old wounds, recounting childhood stories, family memories, and failed ambitions, Falk and Cassavetes embody their characters, impeccably in sync, turning in a splendidly chaotic performance that draws on their long history of working together.

Mikey and Nicky is a brave effort, one that all but ended its director’s career for the simple crime of being true to her vision. It is a shame that the film has been overlooked for such a long time, but an even greater one that Elaine May never recovered from the contentious experience.