“You better come down outta those clouds, boy. Or you’re not gonna be worth the powder to blow you to Hell.”

After Night of the Living Dead became an unexpected smash hit, a young George Romero found himself in an interesting position. How exactly does one follow up one of the most successful independent films of all time and a groundbreaking masterpiece of horror cinema?

His answer—proven wrong by hindsight and corrected after a few missteps—was to pivot in an entirely new direction. Kicking off Romero’s aimless period of artistic wandering, There’s Always Vanilla is a limp romantic comedy about a wayward military veteran at odds with the yuppie culture around him who engages in an affair with a model and tries to get his father laid. Somewhat reminiscent of the talkative projects from John Cassavetes and Woody Allen, there are occasional flashes of inspiration to be found amidst a bland deluge of meaninglessness. Publicly denigrated, disavowed, and sometimes flat out ignored by the director, at the very least it allows aficionados to correct people who say that Romero only directed horror movies. But of course, the thing is, it also proves that Romero should have stayed in his lane.

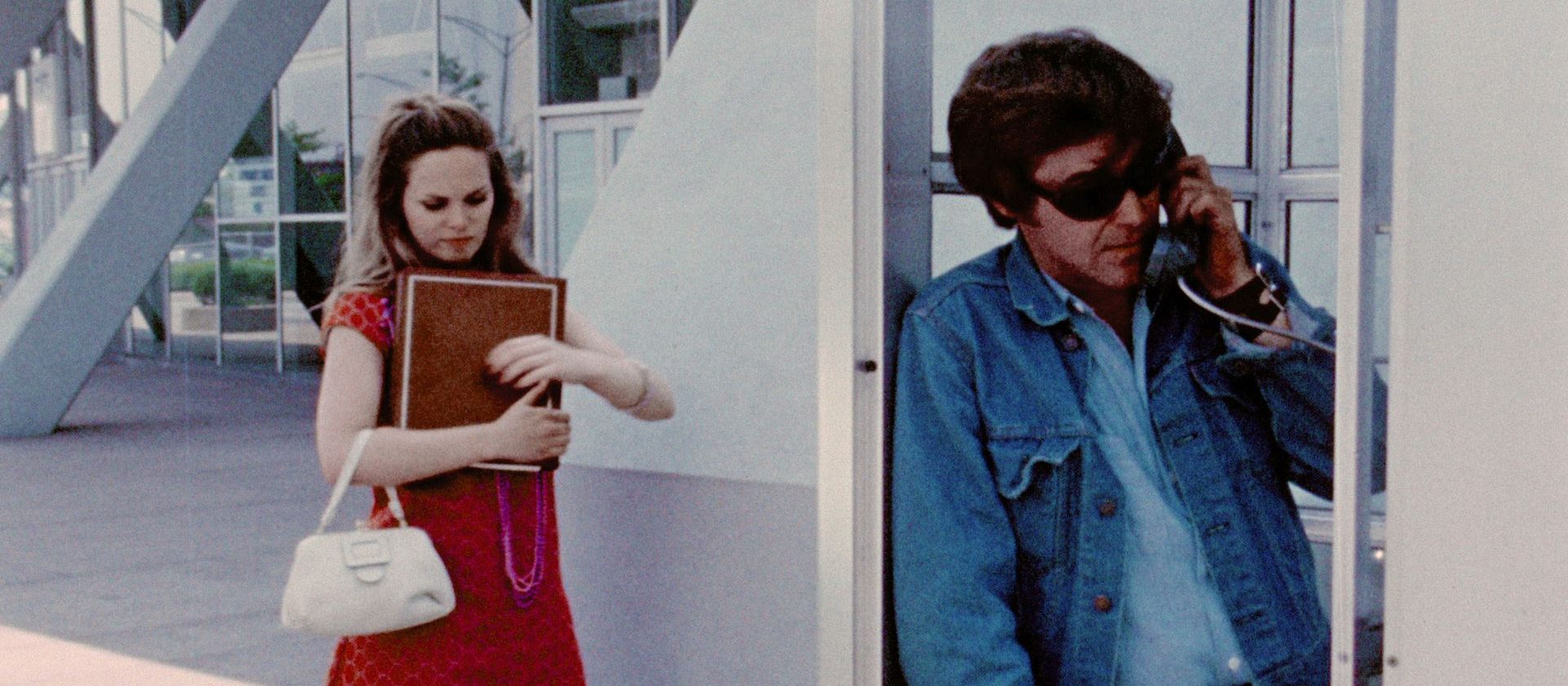

The film opens on an abstract work of art—a bizarre sculpture composed of all sorts of gadgets, gizmos, pulleys, widgets, and other machinery which serves no obvious purpose. Opinions are split on its artistic merit, but most agree that it is an apt commentary on the modern world. The work is the creation of Vietnam vet Chris (Raymond Laine), perhaps the most meritorious thing the rudderless bum does in the entire movie. Outside of this lone feat, he’s more prone to smoke pot, offer shallow pontifications on the absurdities of life to anyone who will listen, and try to hook up with random women, than to do anything worthwhile. After quitting his job as a session musician in NYC, Chris returns home to Pittsburgh and visits his father (Roger McGovern), who encourages him to abandon his faux-bohemian lifestyle and join him in the baby food business. But Chris turns him down because he thinks his refusal to do productive work and the resultant freeloading lifestyle is some kind of noble protest against the War. Or something like that.

But then he meets Lynn (Judith Ridley), a model for beer and toilet commercials who’s used to dealing with ogling executives and so somehow falls in love with Chris despite the fact that he contributes nothing to their relationship. He moves into her flat, eats her food, consumes her drugs and alcohol, and occupies himself by imagining he is creating art. There’s a brief happy-go-lucky head-over-heels period where Chris’s parasitic lifestyle is accepted, but when Lynn gets pregnant, he briefly shapes up and holds down a job at an advertising agency for about five minutes before ditching that too.

That’s the bulk of it. There are a few mildly interesting side trails—a satire about the advertising industry (where Romero cut his teeth), a distressing sequence when Lynn seeks a back-alley abortion so that her child won’t have to grow up with an absentee father (you know, because it’s better to be mercilessly slaughtered in the womb than potentially face a tough life), a scene where Chris tries to set his dad up with a go-go chick to prove that he can still “cut the mustard”; a few flashes of the social commentary that Romero does much better when allegorizing with zombies. Most of these subplots, and even many portions of the central narrative, are incompletely integrated and in quite a few places the whole thing loses cohesion. And yet they also include some of the most fascinating hints of Romero’s future in terms of style and subject matter.

The shortcomings are myriad, but Romero lays quite a lot of blame for the film’s failure on an unproductive screenwriter who left the crew to shoot piecemeal on a delayed schedule with a half-finished script. The incomplete script forced Romero to splice in snippets of Laine narrating directly into the camera and edit creatively to force some semblance of a narrative onto the proceedings. However, as the film roughly stumbles toward its unearned bittersweet coda, it becomes clear that, like his lackadaisical protagonist, Romero cares, but just barely. Almost as if he’d mentally moved on from the project before it was completed. And who could blame him if he did? Like the functionless machine, There’s Always Vanilla serves no purpose other than to aid the viewer in appreciating real art.