![]()

“Don’t you hear that horrible screaming all around you? That screaming men call silence?”

Kaspar Hauser materialized out of thin air one day in 1828, stumbling into the city of Nuremberg unable to speak but a single sentence and clutching a handwritten note about his bizarre upbringing. Though various theories might suggest that the young man was a fraud or a victim of royal intrigue, the letter in his hand claimed that he had been raised in total isolation. Werner Herzog’s biographical film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (also known by its original German title, Every Man for Himself and God Against All), takes Kaspar’s story at face value, but pushes through the surface details to explore what it means to belong to a human society.

After Kaspar was adopted, taught to walk, work, and play music, to think and speak in human terms, he was able to describe his peculiar early life. Chained to the floor of a dim, dingy cell, isolated from all human contact, his only friend was a toy horse. His meals were brought to him while he slept. It was only when his caretaker—if we elect to consider his treatment “care”—taught him how to shuffle his feet, scribble his name, and say “I want to be a horseman like my father once was,” that Kaspar saw another human being for the first time. And then he was introduced to trees, fields, streams, towns, pianos, horses, kittens, chickens, children, and fire, but also pain, pleasure, sorrow, joy, dismay, and so on. All of these were brand new experiences for the overwhelmed Kaspar, who lacked an organic system for categorizing his experiences. Early on, Herzog lingers on a field of grain whipping in the wind, consciously expressing the natural beauty that tends to become unremarkable to someone not locked in a cell for seventeen years but is beautiful nonetheless.

It’s that sense of uninformed, wide-eyed wonder that informs much of Herzog’s film, which begins shortly before Kaspar leaves his cell for the first time. Herzog spends barely any time sketching out the weird origins of his foundling protagonist, preferring instead to take his lump of unmolded clay and toss him into various social situations, seeing how the culture-less alien twists and bristles in the presence high-class snobs, pompous academics, exploitative businessmen, musicians, noblemen, religious clergy. Several years transpire throughout the course of the film as Kaspar is gradually taught reading and writing and proper speech. At one point he’s put on display at a circus next to a midget prince (Helmut Döring, in his second Herzog appearance), a “young Mozart” (Andi Gottwald), a flautist, a somersaulting bear, and a fire eater; an episode which is echoed when he is introduced to high society as a novel curiosity. Other scenarios play as idiosyncratic, amusing, and occasionally profound. For every freakout caused by a hypnotized chicken, there’s a thought-provoking moment such as when Kaspar discovers the sensation of crying.

Perhaps the most striking element of the film is how Kaspar seems to understand certain things, while remaining completely incapable of grasping others. In the film’s commentary track, Herzog notes that Hauser was a unique specimen. There had been children raised by wolves and other animals before, but Kaspar Hauser never learned to be part of a social order. He was not taught to interact with other living beings, to fear danger, to form words with his mouth. He ignores the flame that licks at his face and remains unperturbed when a sword point nearly pierces his temple. As Seth Katz points out, it’s apparent that Kaspar missed the mirror stage of his brain development. That is to say, he never made the connection that his own body exists in the same physical space as the forms he observes around him.

Just a few days ago I witnessed a puppy going through this for the first time at ten weeks old; Kaspar was almost twenty when he became aware of his own body. Huge gaps also exist in his superficial grasp of language and his radical conception of the universe, leading to strange utterances like, “nothing lives less in me than my life,” as well as some shocking beliefs: among them that a two-story tower requires a two-story man to build it, that an apple moves of its own accord just like any other creature; and that his prison cell, which surrounds him while he is in it, is much larger than the prison itself which disappears when he turns away from it. (That last bit might once again evoke the terrifying and perplexing thought that before Kaspar’s initial release, his confinement wasn’t a claustrophobic nightmare because his dungeon was the entirety of his universe.) In one of the film’s true laugh-out-loud moments, a philosopher presents him with a tricky question: if there was a village of liars and a village of truth-tellers, and you met someone on the road between them, what question could you ask to determine which village the traveller hales from? “I should ask the man whether he is a tree frog,” says Kaspar, pragmatically slicing right through the logician’s thorny problem.

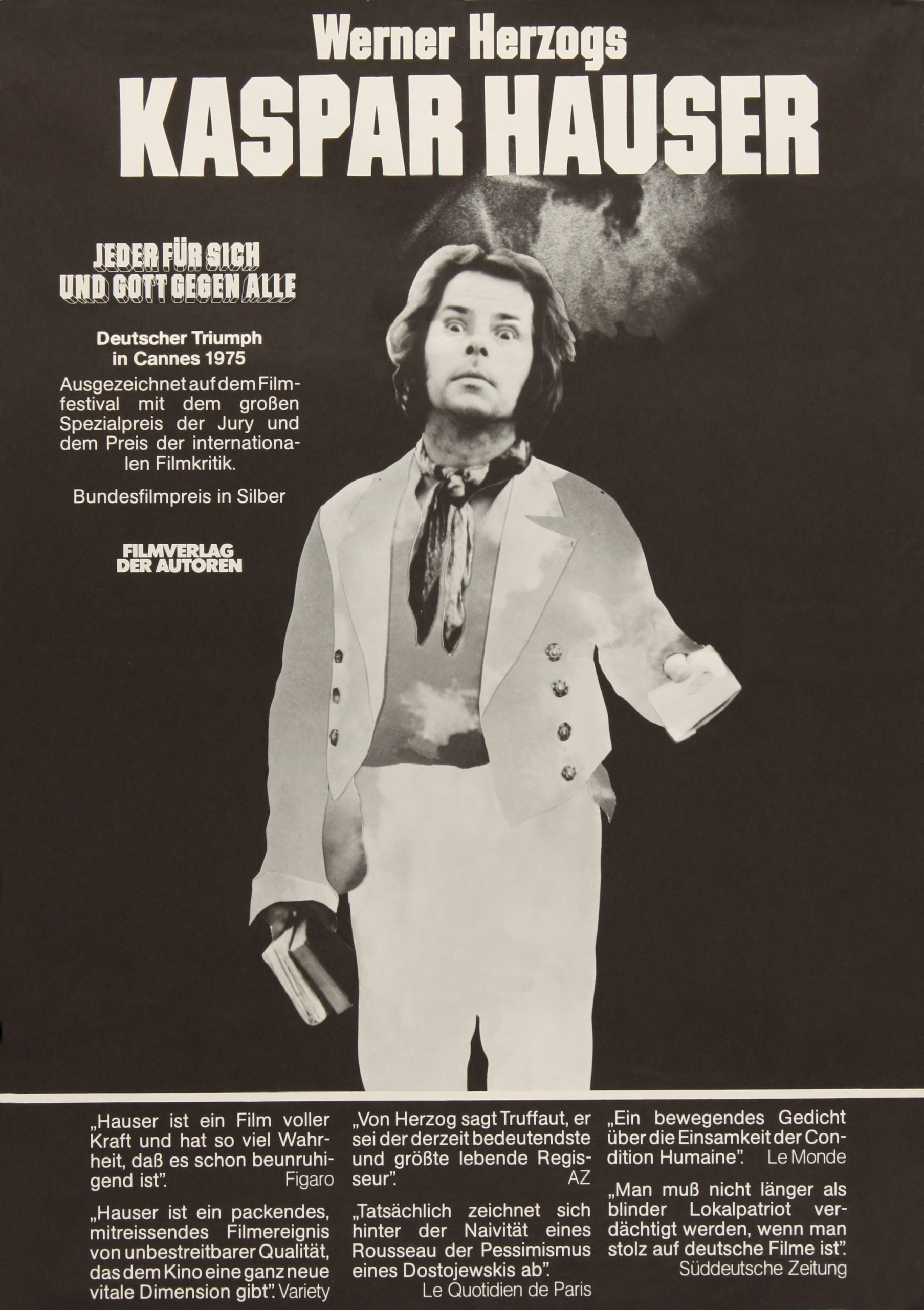

Herzog’s master stroke here is the casting of Bruno Schleinstein as Kaspar Hauser. Credited only as “Bruno S.” to heighten the sense of mystery, Schleinstein was nearly as odd a character as Hauser himself. Born of a prostitute, in and out of mental institutions since a young age, Schleinstein was a non-actor who Herzog discovered in a documentary about street musicians. He was self-taught on the piano, accordion, and glockenspiel and drove forklift for a living. His performance is full of bug-eyed bemusement, physical clumsiness, and stilted speech. It’s slightly comedic at times. Perhaps deliberately so. Fittingly, music is one of the only things that transcends all the barriers between Kaspar and his fellow humans (there’s another nice cameo from Florian Fricke as a blind pianist), allowing him to join together with them in uninhibited enjoyment.

Herzog is certainly playing fast and loose with history, more interested in a mood conjured by image and sound than in accurately portraying his subject (even if he is often credited with sticking to the broad facts). Throughout, he weaves in languid passages of classical music and landscape, sometimes whacky shots of various animals, using his film style to echo the increased intellectual capacity and interior life of his subject. Kaspar relates several dreams, notably one in which a mass of people are all struggling in vain to scale a mountain in dense fog. These hazy excursions culminate in a wonderful sequence on Kaspar’s deathbed where he describes a vision of nomadic Berbers wandering in the Sahara Desert, led by an old blind man and traveling on donkeys. This climax, and the film as a whole, point to Herzog’s motive: not to solve the enigma of Kaspar Hauser, but to revel in its mystery, to enhance its macabre qualities and gently unnerve the audience by presenting them with something wonderful and strange.