“You think when you reach a certain age things will start making sense, and you find out that you are just as lost as you were before. I suppose that’s what damnation is. The pieces of your life never to come together, just splashed out there.”

One time when I was going to be spending a night away from home, my sister came to my house to have a sleepover with my wife. They were planning to watch a movie together. Before I left I noticed that they had selected The Tree of Life from the DVD wall. It had a nice blurb on the back and Brad Pitt’s name on the front. What could go wrong? I tried to talk them out of it, suggesting that it might be too abstract for their liking, but that only fortified their conviction that they could handle it. Suffice to say that they should have listened to me. In any case, when my wife asked if I thought she would like Knight of Cups, I told her not to bother.

I was right again. She would have been bored to tears by Terrence Malick’s contemplative odyssey. But I liked it, though I don’t have it in me to love it as I do some of his other works. I liken it to sample-based ambient music, specifically The KLF’s Chill Out. That landmark album presents an impressionistic aural journey throughout the Gulf Coast states, stitching together seemingly disparate sounds—field recordings of rolling train cars, birdsong, dog barks, running water, pedal steel guitar, synths, radio station chatter, Tuvan throat singers, Fleetwood Mac, Elvis Presley. These elements cumulatively amount to a hallucinatory sonic experience.

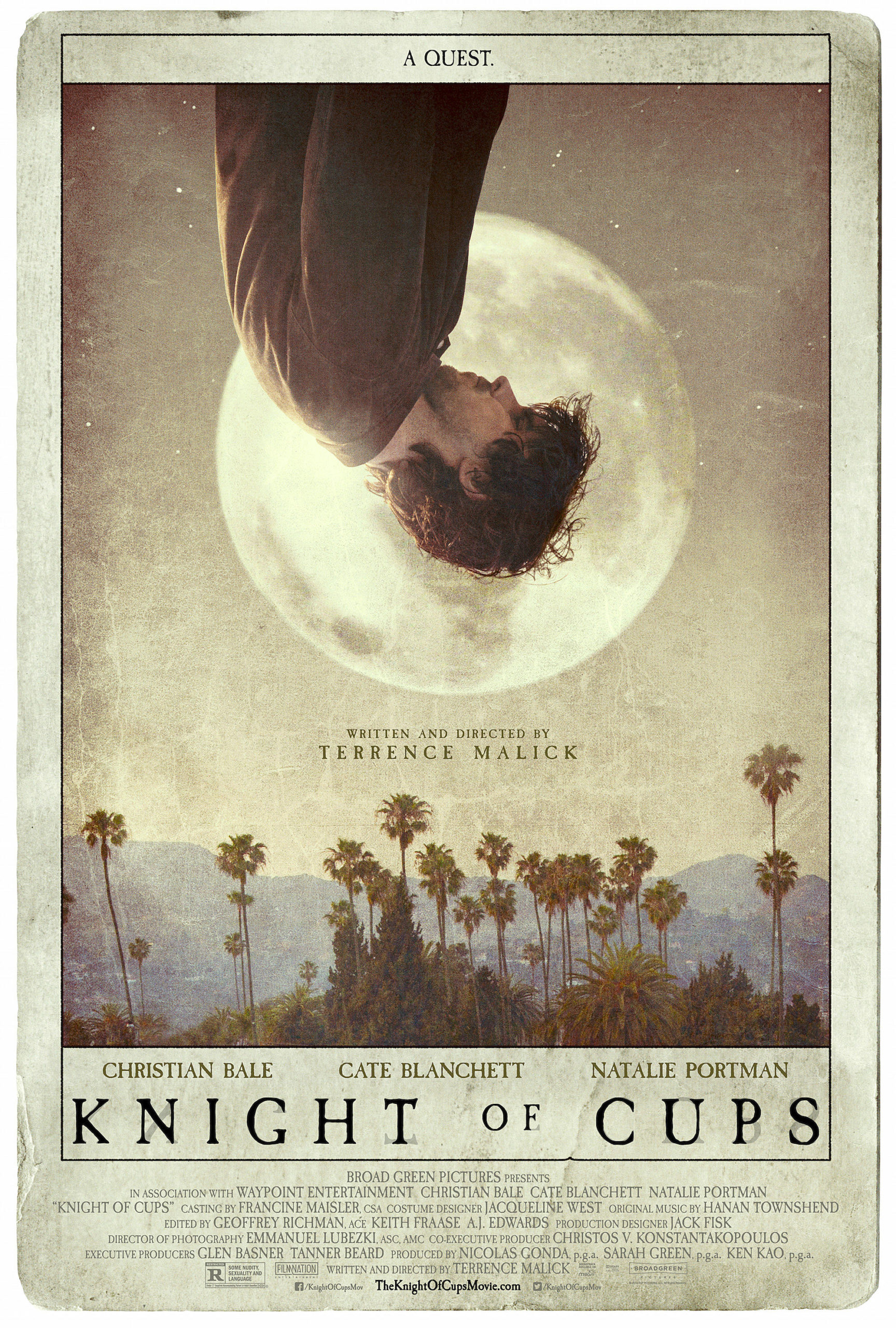

Knight of Cups is similarly dreamlike, throwing its scattered vignettes at the audience in a headlong rush of half-forgotten memories and muted reality. These diverse snippets are blurred together by the central figure’s growing reliance on drugs and alcohol, consumed in order to cope with an empty, tragic life and a fruitless search for transcendent faith. The film takes its name and its chapter intertitles from Tarot—medieval playing cards that have been repurposed for occult practices in modern times. In divination, when presented upright, the Knight of Cups represents exciting change and new opportunities. The Knight is refined and intelligent, artistic and dignified, and constantly in pursuit of his latest interest. But when presented upside-down, the Knight represents recklessness, fraud, broken promises, and deception; a man incapable of discerning truth from lies.

Rick (Christian) is Malick’s upside-down Knight of Cups. Formerly a hotshot Hollywood screenwriter, Rick has experienced the kind of success that others can only dream of. He’s cruised down stretches of open road in convertibles with pretty girls whispering jokes in his ear as his unkempt hair blows in the wind. He’s gone to all the fancy parties and rubbed shoulders with all the big names. But his life is empty save for constant despair, his thoughts haunted by the death of one brother and the dire circumstances of the other (Wes Bentley). He’s numb from family trauma and unable to collect himself, incapable of focusing clearly on the present, the past, or the future. In the dawn’s early light, with his fellow imbibers still passed out on the floor around him, he paces an extravagant party venue in emotional agony, wondering when the trajectory of his life was diverted from a righteous path.

In addition to Tarot cards, Malick draws inspiration (and sometimes directly steals) from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and the apocryphal “Hymn of the Pearl”. (There’s even a brief sound sample from Twin Peaks!) As Rick’s father Joseph (Brian Dennehy) tells us in a lyrical voiceover, Rick was once a prince on a quest to find a priceless pearl in the depths of the sea, but the people poured him a drink that caused him to lose his memory; to forget that he was the son of a king. Now he is lost, not in some biblical backwater, but the sprawling excess of modern Los Angeles.

As Rick mutely stumbles through debauched parties and empty conversations, he encounters and engages with numerous women—played by Imogen Poots, Cate Blanchett, Freida Pinto, Teresa Palmer, Isabel Lucas, and Natalie Portman. These women function as tour guides of various religions. Rick is paraded around Zen gardens, kitschy statues of Roman gods, Hindu shrines, Buddha sculptures, museums of classic Christian art. But these brief flings, too, are insufficient in drowning out Rick’s personal struggles. Woven into these scenes of tepid romance and spiritual yearning, without any clues to demarcate fact, fiction, and fantasy, are scenes featuring Rick’s brother and father. Most affecting is his father’s admission that he hasn’t been an example for his son to follow; that he believed in a righteous path but did not walk it as he wished to.

Knight of Cups is less coherent than some of Malick’s other recent works, The Tree of Life included. It’s composed entirely of incomplete snippets of scenes, fragmented conversations, elliptical narration; broken apart and glued together with music, nomadic cinematography, and voiceover poetry. Grainy home video and what looks like GoPro footage are mixed in with conventionally beautiful shots from Emmanuel Lubezki. Some gravitate toward this bold style, but the film is so committed to defying expectations that many have found it to be highfalutin nonsense. They do not interpret the impressionistic editing, with its harsh juxtapositions and jarring cut-offs, as reflective of a confused inner state, as something like our own muddled interior lives, but as self-indulgent noodling shot through with empty spiritual themes that can only have meaning for the person who made it. They do not glean anything from its beautiful imagery and poetic narration and universal themes, nor its wild formal experimentation.

So is it a lumbering mess? An aimless rumination? Everyone’s entitled to their opinion, and I think that is especially true for a Rorschach test like Knight of Cups, but I think it is hard to deny the film entirely. By ignoring most requirements of commercial filmmaking, Malick has crafted a true work of art, which almost by necessity means that it won’t be everyone’s cup of tea. But for viewers of a certain temperament, it proves to be a moving meditation on the fleetingness of life, the limits of the human mind to contextualize our traumatic experiences, and the search for individual purpose and meaning. Much depends, of course, on what the viewer brings to the film. If there’s nothing for the mind to chew on in the background, Knight of Cups will indeed feel fractured and meaningless. But if you treat it like ambient music—something to occupy part of your brain while the other part wanders down strange trails—it’s quite interesting.