“I have no one, no son or brother, to help me out. I’m just a good-for-nothing old man.”

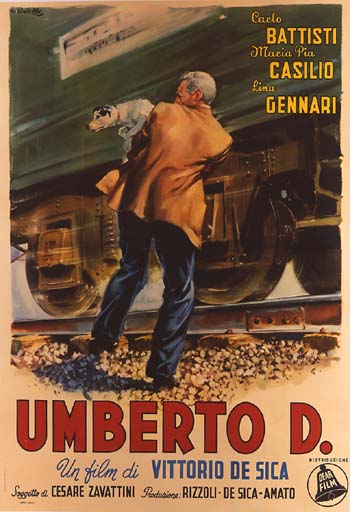

Vittorio De Sica listed Umberto D. as his personal favorite from his vast oeuvre that spanned several decades and includes at least two seminal works of the Italian neorealist movement, Shoeshine and Bicycle Thieves. It was also considered a formative influence by Ingmar Bergman and Martin Scorsese—the latter of whom seems to have seen every fringe classic foreign film that’s ever been thrown up on the silver screen, not to mention the great lengths to which he’s gone as a preservationist of world cinema.

It’s not difficult to see why Umberto D. is so highly regarded. Centered on a sympathetic but bristly old man and his loyal dog, blended around the edges with subtly rendered social commentary, it presents a sentimental story about a futile search for lost dignity in a world of anonymous indifference. It evokes pathos at every turn as our hapless protagonist fumbles around, too prideful to ask for help outright but too hemmed in to think his way out of his predicaments. That being said, to denigrate the film for its maudlin tendencies, while containing a grain of truth, would be unjust. While the attention given to the affectionate relationship between the old pensioner and his obedient mutt with “intelligent eyes” is plainly lachrymose—especially the ending—there’s a grittiness and inner tension to the picture that belies the notion that it merely exploits our emotions. That is to say, it earns its sympathies the hard way.

Umberto Domenico Ferrari (Carlo Battisti) was once a respectable man. In many ways he still is. He dresses sharp, his manners are refined, he speaks eloquently. But in one important way he is not: he’s run out of money. Inflation has done its work and the meager pittance granted him by the Italian government is no longer sufficient to sustain the bourgeois lifestyle to which he’s become accustomed. With the false sense of importance that comes along with perceived social status quickly evaporating before his very eyes, Umberto realizes that he has little to live for. No job, no family, even his health is failing. While he’s out protesting his minuscule pension along with a gaggle of other picketing malcontents, his landlady (Lina Gennari) rents out his room to an adulterous couple at an hourly rate. He complains about the invasion of his private quarters, but then she launches into a tirade about the several months worth of back rent that he owes her. And so we follow Umberto as he tries to avoid falling from poverty into shame, trying to hawk his watch to some old acquaintances, parting with a number of treasured tomes, and skipping meals.

Stuck inside the same prison that Umberto calls home is the housemaid Maria (Maria-Pia Casilio), perhaps Umberto’s only true human friend. But she too has problems and these preclude her from offering material help to the persnickety old man. Pregnant by one of two boyfriends, one from Florence, the other Naples, Maria spends her days in a dull routine. In one noteworthy sequence we witness the maid perform her morning chores. Shambling over to the stove, she lights a match on a wall hideously grooved from a thousand other match strikes. She douses a battalion of ants that are dancing around on a nearby wall (though sometimes she’ll spice things up by using a makeshift torch to break up the crowd). Then she sets her mind to the grinding of coffee to fuel another day of resigned exhaustion. Umberto and Maria understand one another, and there is mutual affection, but neither can do much for the other beyond empathize.

Importantly, Umberto does not spend much breath railing against the injustices of the world. He does mention that an increase in his pension will help him pay off his debts, but once he realizes that it’s not forthcoming, he sets about taking care of his business with despondent dignity. Eventually, he will come to contemplate the notion of suicide, but his chief hang-up is the fate of his beloved pooch, Flike. In no uncertain terms, Umberto’s own needs are formed by the needs of his dog. He can skip meals, but he won’t let Flike go hungry. He can live on the street, or lay down on the train tracks, but Flike needs a home. There’s one remarkable scene in which Umberto witnesses a man begging and entertains the idea. He holds out his hand but just as a charitable soul reaches out to offer him a handful of change he snatches the hand away and pretends to have been feeling for raindrops. Unable to overcome his pride and beg for donations himself, he enlists Flike’s help. Standing on his hind legs and holding his owner’s upended bowler hat in his clenched teeth, Flike dutifully stares down passersby with his puppy dog eyes while Umberto hides in the distance. Alas, the bemused strollers walk past the dog without contributing. Very quickly, Umberto decides that he’d rather demean himself than Flike. In the end, it is Flike’s unflagging loyalty that saves Umberto from himself.

Italian neorealism, a film movement born during the final years of WWII, placed an emphasis on stories of everyday life, set in real locations, featuring non-professional actors. Umberto D. is one of the most successful instances of that theory working in practice. Carlo Battisti, who was seventy years old at the time, gives a modest, humble, and most importantly, believable performance as the title character. He would never act again, leaving behind Umberto D. as his sole contribution to cinema. Such is not the case for Maria-Pia Casilio, who would go on to act in numerous films throughout the ‘50s (including several more De Sica pictures) and then sporadically thereafter. Both of these untrained actors embody the ideal “uncarved block” from which a naturalistic performance might emerge.

Nevermind that the faux-happy ending leaves Umberto’s problems unsolved. It affirms life, and in that sense deserves mention alongside such films as It’s a Wonderful Life and Ikiru.