“Everything has a price. The great struggle in life is coming to grips with what that price is.”

All the Money in the World is a serviceable thriller, smoothly directed from an uneven script, that is overshadowed by elements external to it. Most notably, with barely more than a month left until the film was scheduled to hit theaters, director Ridley Scott elected to reshoot large portions of it in order to excise disgraced star Kevin Spacey from the final product (apparently Spacey got taken off of the “allowed to sexually abuse minors without repercussions” list).

Compounding this distraction is the matter of Wahlberg’s clever contract, which allowed him to pocket a cool $1.5M for the reshoots with Spacey’s replacement, Christopher Plummer, while top-billed Michelle Williams received a pittance. That revelation opened a whole can of worms about equal pay, ignoring the fact that Wahlberg is simply a bigger star than Williams and thus could make such demands. Credit where it’s due, Wahlberg then donated the money in Williams’ name.

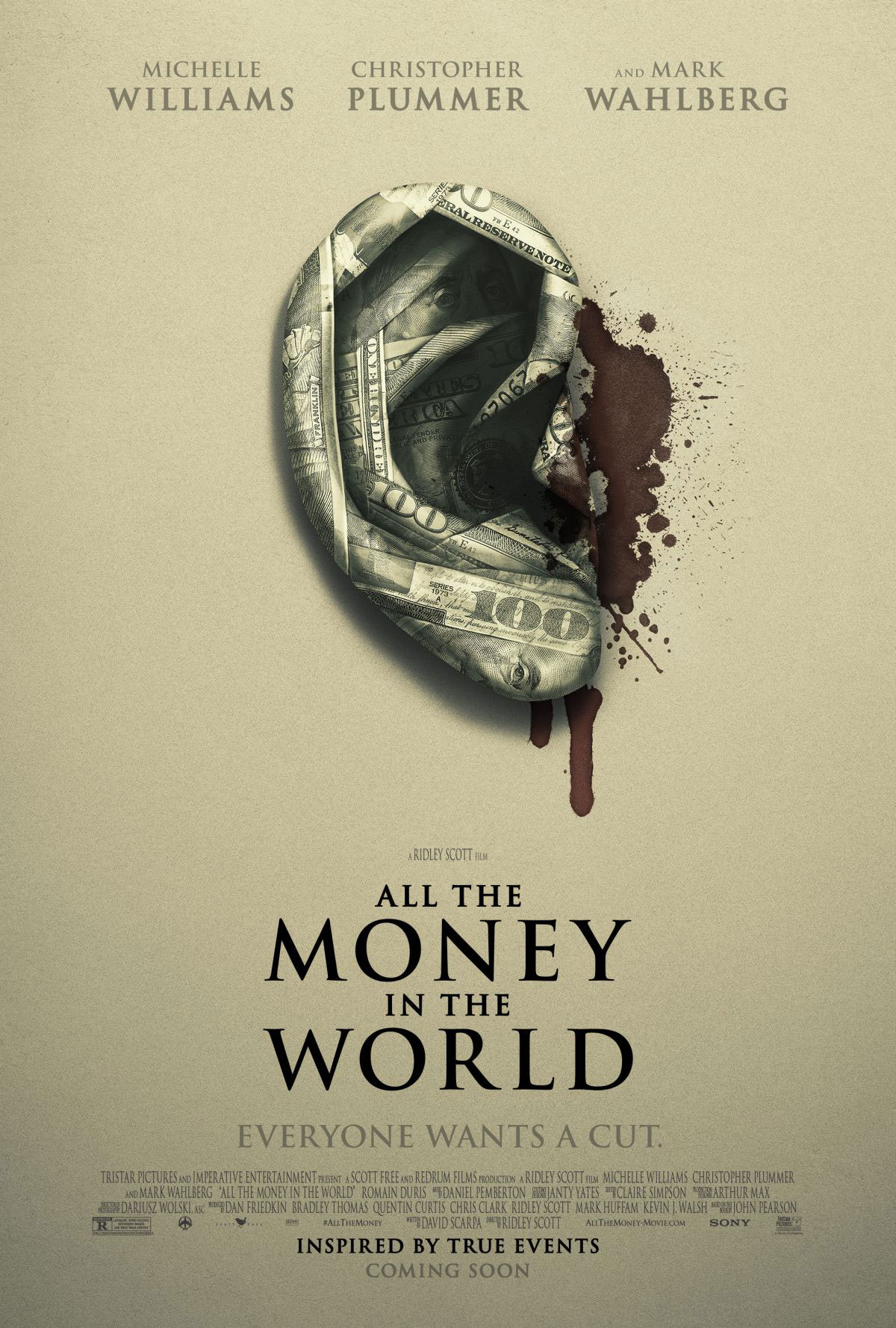

All of these extraneous issues serve to mask what happens to be a captivating true story: that John Paul Getty III, grandson of the richest man in the world, was kidnapped in 1973, and his grandfather refused to pay the ransom. The tight-fisted oil tycoon (Plummer) reasoned that if he paid one ransom, his fourteen other grandchildren would become targets for kidnapping in the future. (Listen to this podcast for a fascinating discussion on the predictable nature of ransom negotiation.) It was the boy’s mother, the tenacious Gail Harris (Williams), now divorced from Getty the Second and thus disconnected from her former father-in-law, whose persistence ultimately saw her son home sans a hacked-off ear.

All the Money in the World is loosely based on John Pearson’s nonfiction account of the kidnapping, Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty, but David Scarpa’s script takes numerous creative liberties to liven up the story. Quickly detailing the rise of the Getty oil empire, it moves directly into the slimy details of the kidnapping episode. Snatched off the streets by Italian mobsters while galivanting around in Rome and flirting with ladies of the evening, Getty III (Charlie Plummer—no relation) soon finds himself living in captivity, writing letters to his mother begging her to pay the ransom. But of course, she can’t, because she has no money herself and good old granddad won’t spare a cent, even though the profitable oil crisis meant he was accruing more than enough money to cover the boy’s $17M ranson every single day. While unwilling to part with any of his vast wealth, Getty decides that he will send his head of security, former CIA operative Fletcher Chase (Wahlberg) to track down his grandson.

When Christopher Plummer is on the screen, All the Money in the World crackles. When the movie strays away from his magnetic performance for too long, it begins to drag, and the performances range from solid to mediocre. Unfortunately, it is Wahlberg, of whom I am quite fond, that seems most out-of-place. He turns in a wooden performance in a role that doesn’t play to his strengths and single-handedly undercuts much of the drama. Williams, though she never quite finds the right tone and slips in and out of a put-on accent, is solid. Likewise I found myself drawn to the performance of Romain Duris as a sympathetic kidnapper who eventually aids in the younger Getty’s escape.

Although the kidnapping plot is what arouses our interest, it is the script’s occasional rumination on the elder Getty’s perverted sense of purpose that provides the film with its depth. Here’s a man who openly admits that he broke contact with his own children in order to raise his oil empire. “I had to focus on my mission, you understand?” he tells his son (Andrew Buchan). “On my business. And I couldn’t be weighed down mentally with a family. You understand that, don’t you, Paul?” And yet this same man is unwilling to forgive his son’s ex-wife, who offered to leave all pecuniary considerations on the table during the divorce proceedings in exchange for full custody of her children—an offer that he accepted, but tries to renege at the time of the kidnapping by agreeing to pay the ransom fee only if (and only if) Gail will sign over custody of all three of her children to her drug-addicted former husband. Here’s a man who committed himself so entirely to the accumulation of material wealth that, once he has it, he no longer possesses any capacity for human relations outside of ruthless negotiation; who finds more “purity” and “beauty” in his vast collection of priceless artifacts than in his own flesh and blood; who does his own laundry to save money and tells his grandchildren the mass-produced trinkets he gives them are priceless artifacts from his private collection.

Despite some questionable dialogue, Plummer’s excellent turn as the idiosyncratic magnate is so compelling that it creates a drastic imbalance between his supporting role and the main plot. Ridley Scott’s production is excellent from a technical perspective—a fiery escape attempt is particularly invigorating—and radiates a pleasant ‘70s vibe with its tense discussions, classically-arranged scenes, and on-location shoots. Ultimately, though, the film falters because the kidnapping would better serve as an illustrative side plot to the elder Getty’s story instead of the other way around.