“Fancy words and old ways don’t cut it now. We need something with a fresh nip to it.”

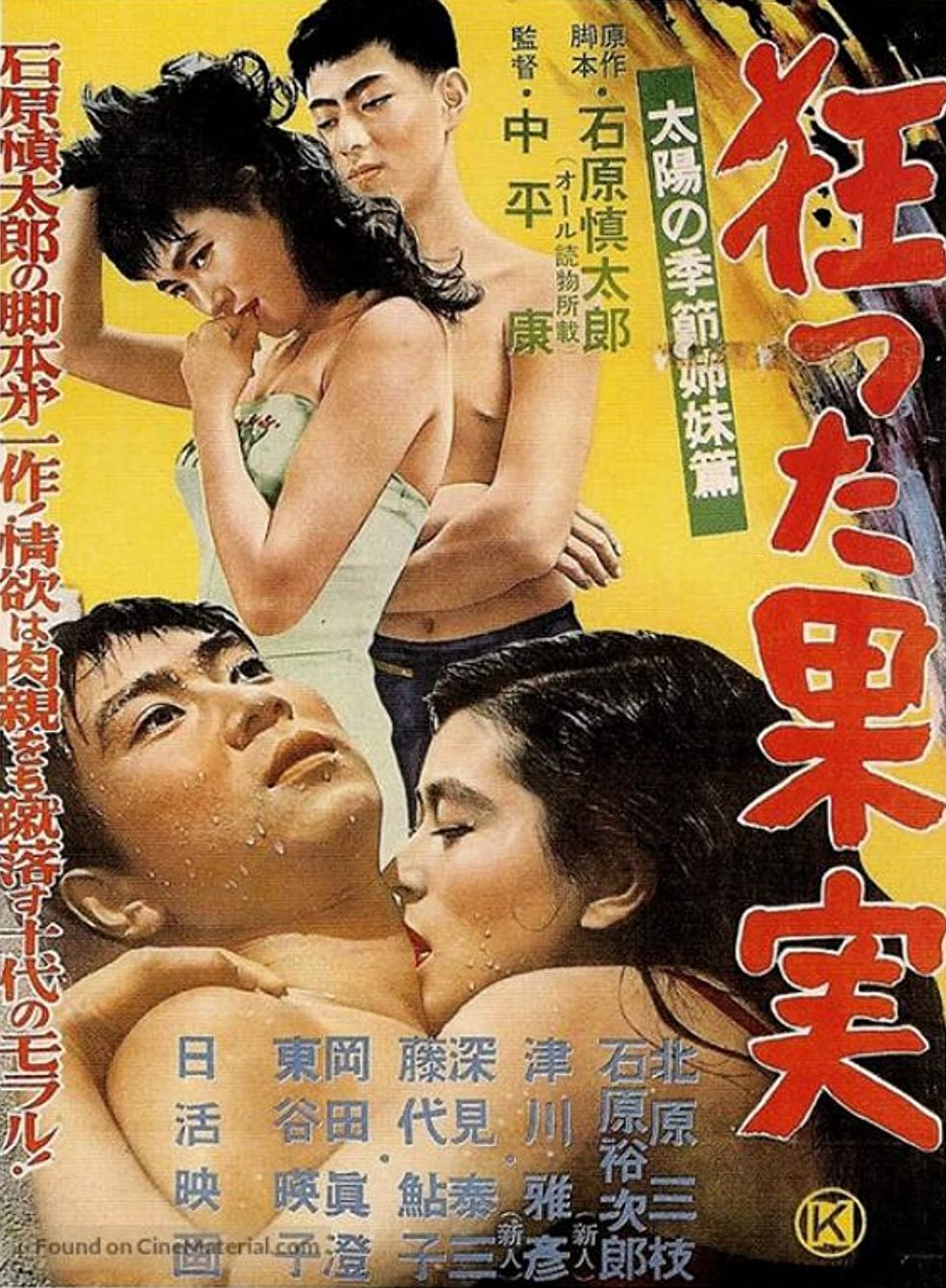

Cited as a precursor of the Japanese New Wave, Kō Nakahira’s debut feature, Crazed Fruit, is an unsentimental drama marked by a youthful sense of rebellion against the traditional Japanese way of life. Insolent and narcissistic, the film’s subjects challenge the culture of their forebears, a culture that they find boring and clichéd. In their eyes, the pithy moralisms and worn-out customs that worked for centuries are insufficient for such a sophisticated generation. These youngsters are so sophisticated, in fact, that they cannot find anything to satisfy their uncertain appetites. They’re ready for something, but they don’t know what it is. And so they lay around, hampered by an inescapable sense of debilitating ennui, halfheartedly discussing girls, lazily playing cards, absentmindedly plucking stringed instruments, occasionally relieving their inner turmoil by indulging in carnal relations.

The story is rather simple. Two brothers, the older, streetwise and sexually experienced Natsuhisa (Yujiro Ishihara) and the younger, naive and innocent Haruji (Masahiko Tsugawa), both find themselves infatuated with a lovely young lady named Eri (Mie Kitahara) during their summer vacation on the Zushi coast. Haruji spies her first, at a crowded train station, prompting a rowdy hustle through the sea of passengers so that his brother can confirm he’s seen a beauty. Shortly thereafter, the trio reconnect by chance when the brothers happen to find Eri swimming a long distance from the shore while cruising around in their motorboat looking for girls. They give her a ride back into the harbor, each taking stock of their catch in different ways.

Natsuhisa teases his little brother, telling him he doesn’t have a chance, secretly hoping that Haruji will lose hope and give him an opportunity to make a play of his own. But Haruji only becomes more determined to court a girl that will satisfy his adolescent urges and earn him a newfound respect among his friends. He invites Eri to a party with the rest of the brothers’ clique—where the stated aim of the shindig is to see which fellow can bring the prettiest girl—and she charms the whole group with her looks and charisma. As the party wanes, the pair sneak off in Natsuhisa’s car and head to the privacy of the beach, tenderly caressing and kissing under the light of the stars. It’s a magical evening. Quite obviously, Haruji is smitten, and Eri seems to genuinely enjoy the attention he lavishes on her. But Eri is not the innocent young maiden that Haruji believed her to be. In fact, she’s married to an older American businessman who remains unaware of her numerous adulterous adventures.

Natsuhisa catches wind of Eri’s misdeeds, though, and when he does he uses that knowledge to blackmail her. Soon, Eri finds herself in a nasty love triangle (or quadrangle?), trying to carry on extramarital affairs with both brothers while keeping Haruji’s innocence and sense of morals intact. Natsuhisa, initially pleased with his amorous conquest, finds himself gradually torpefied, resentful of the other men who enjoy the pleasures of Eri’s body, but terrified of coming clean with Haruji and ending his idyllic summer.

In post-war Japan, a number of subcultures—tribes if you will—emerged as a result of the cross-pollination between America and Japan. Various groups formed around shared passions like motorcycle racing, rock ‘n’ roll, psychedelic drugs, and figurine collecting. The members of the Sun Tribe, named after Shintaro Ishihara’s novel Season of the Sun and their penchant for lying on the beaches to catch a tan, were known for their recklessness and ambivalence, a rough analog of the greaser and rocker subcultures in America. Indeed, if Crazed Fruit (based on another Ishihara novel) is any indication of the Sun Tribe with its girl-chasing, sports car-driving, clubbing, drinking, gambling, and so on and so forth, then these boys would fit right in with James Dean and company. Reflecting the youth culture’s break from traditional norms, Nakahira’s direction proves quite uninhibited, making free use of extreme close-ups, canted frames, symbolic shots of legs and feet, and inventive editing techniques. It is this creative flair as much as the subject matter and unforgettable climax that mark Crazed Fruit as a forerunner of the Japanese New Wave.

The film’s greatest merit lies in how it looks forward with a measure of trepidation. In the character of Haruji we can see a culture in transition. He’s a young man for whom the war is a hazy early childhood memory, who’s grown up in a Japan far different from the one his parents and grandparents inhabited; one influenced by U.S. culture and politics. And yet even as Haruji wishes to fit into his malaise-inflicted social group, he’s not quite ready to jettison traditional values entirely. He occupies a middle ground, one foot in the past, another in the present, connected to neither. He’s caught between a desire for simpler times, when courting norms existed, education was valued, and young people remained chaste; and a desire to follow in his brother’s footsteps and live in the moment like a hedonist, satisfying his fleeting urges with endless nights out and loose women.