“That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

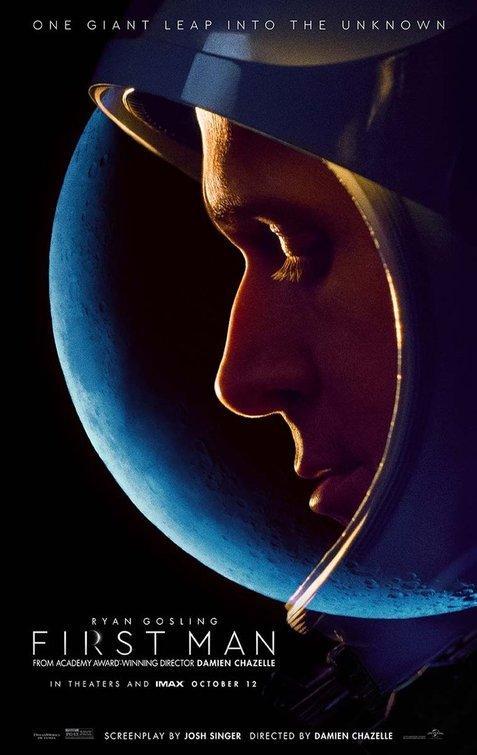

Before its release, Damien Chazelle’s biopic of Neil Armstrong was derided for its perceived political stances. Attacks came whizzing in from both the left and the right. Conservatives cried foul at the director’s decision to not show the iconic planting of the American flag on the moon; as if the abundance of stars-and-stripes elsewhere in the film did not sufficiently compensate for the choice to emphasize Armstrong’s personal drama on the lunar surface. That the 1960s space race was pioneered in America by white men at NASA gave the progressives plenty of ammo to cry foul about racism and misogyny; as if it was morally wrong for Chazelle to primarily focus on the astronauts and their families (and as if Hidden Figures hadn’t just come out a couple years prior). Targeted from all sides, First Man became an unfortunate victim of the culture wars—a casualty of the concerted effort by seemingly everyone with a visible platform to be mad about something or other.

It’s perhaps too easy to get hung up on the film’s benign controversies. Initially, after a few festival screenings, rumors started swirling that the American flag was entirely absent from the picture—that it didn’t appear in a single frame. While a negative reaction to such a slight may be understandable, it’s a simple matter of fact that no such slight exists. Old Glory is all over the place—sewn onto space suits, waving by the thousand in archival footage of enthusiastic crowds anticipating liftoff, etc. It’s even quite clearly shown on the moon after it’s been planted! But that didn’t stop pundits (and even sitting U.S. Senators and the President himself) from flinging vitriol prior to watching it for themselves. And once it was clear that First Man did indeed contain many depictions of the flag, not to mention JFK’s famous speech or “UNITED STATES” emblazoned vertically on the side of a rocketship, it was too late. The rage machine was already chugging along at full speed, so it just shifted focus, zeroing in on the lack of the flag-planting on the moon in particular.

Leading man Ryan Gosling made matters worse by emphasizing that Armstrong did not view himself as an American hero; suggesting that the moon landing was a “human achievement” (yeah, a human achievement paid for by the American taxpayer, came the angry replies). However, contrary to the early conservative hysteria, First Man is decidedly unmarred by progressive revisionism. Far from it. But even though it is plenty patriotic, it’s not exactly hagiographic in its depiction. That’s because it’s not strictly about the prolonged American effort to put a man on the moon, but the life of the first moonwalker himself; a life marked by sacrifice and perseverance and personal struggles barely related to space at all. In any case, once it became clear that the film wasn’t particularly subversive regarding the popular conception of the space race—i.e. it was okay for conservatives to like it—as a matter of course progressives decried the film’s predominantly white male cast and its rosy depiction of an earlier era of American life.

But, like I said, all of this hullabaloo distracts from the film itself, which is a shame because it is quite well done. From the tactile recreations of the test craft and launching stations, to the pseudo first-person perspective during the nauseating excursions into space, to the breathtaking visual rendering of the lunar landscape, to the economical sprawl of a story that traces the highs and lows of Armstrong’s life and career while maintaining the larger scope of the space race between the Soviets and Americans—First Man is an affecting picture that captures the enterprising spirit and drive to achieve that made one proud to be an American decades before I was born.

Moving quickly between short, illustrative vignettes, we follow the Armstrong family through nearly a decade of their lives. Beginning in 1961, when Neil was a NASA test pilot crashing an X-15 plane in the Mojave Desert, the film flits through Armstrong’s career trajectory: his application to the Gemini program, his years of extensive training, several near-death experiences that leave him bruised and burned, and the ultimate culmination as he leaves the first footprints on the moon along with fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin (Corey Stoll). With excellent sound design, faithful, nuts-and-bolts recreations of spacefaring vessels, and a selectively jittery camera, Chazelle achieves a gritty physicality that make the years of NASA training and spaceflight itself appear to be ninety-nine parts hell, one part euphoria. “We need to fail down here so we don’t fail up there,” Armstrong says as he trudges through a field with blood dripping from his singed forehead, the remains of a failed prototype lunar lander smoldering behind him. This after he had survived a Gemini mission by the skin of his teeth, barely remaining conscious when his partner (Christopher Abbott) blacked out as their spacecraft malfunctioned and sent them spinning out of control. “At what cost?” NASA director Bob Gilruth (Ciarán Hinds) asks him. “Don’t you think it’s a little late for that question?” he replies.

While a cowboy retelling of the story might have skirted around the failures, or more probably used them as the building blocks of the future success, First Man defines its story by its various setbacks. Consider that by the time Armstrong is calmly walking away from the various piles of burning debris that might have killed him, he’s witnessed the drawn out death of his firstborn child from a brain tumor; or that the majority of the astronauts who moved with their families to Houston along with the Armstrongs died during failed missions, including Ed White (Jason Clarke), Elliot See (Patrick Fugit), Roger Chaffee (Cory Michael Smith), and Gus Grissom (Shea Whigham). It’s fitting then, that Gosling’s portrayal of Armstrong finds him gazing inward, struggling to connect to other people, and unflinching under extreme duress. Even though we know Armstrong and NASA will succeed, this atmosphere of repeated failure and loss produces a sense of doubt within the man and the organization. This is emphasized during a montage sequence in which Chazelle widens his scope to show political opposition to the extravagant costs of space exploration, highlighted by a performance of Gil-Scott Heron’s (Leon Bridges) spoken word poem ‘Whitey on the Moon’ delivered to a swaying mass of riotous hippies—“I can’t pay no doctor bills, but whitey’s on the moon. Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still, while whitey’s on the moon.”—and archival footage of Kurt Vonnegut suggesting that “an inhabitable New York City” might be a more suitable goal.

First Man delivers its most effective blows when it focuses on the uneasy family dynamic in the Armstrong household. Anchored by a strong if underwritten performance from Claire Foy as Armstrong’s wife Janet, Chazelle depicts the Armstrongs’ home life in a constant state of debilitating anxiety, every pre-mission goodbye perhaps the last moment they’ll share together. Prior to the Apollo mission that sends him to the moon, Armstrong is found stoically packing his suitcase while his children prepare for bed, clearly avoiding an awkward farewell that he cannot articulate. Janet demands that he sit down and explain the reality of the situation to his children, and the scene that plays out with equal parts humor and excruciating tragedy as he answers their questions like he’s representing NASA to the press. It reveals a startling inability to relate to other human beings that’s only hinted at elsewhere. The man who can remain conscious while whirling about in space and pull off emergency landings without panicking, who will shortly leave a footprint in lunar soil, cannot relate to his own children. Is this inherent in Armstrong or a result of his intense focus on his work? As much as we are encouraged to consider the cost of the Apollo missions in the form of wasted taxpayer dollars and dead astronauts, we must also consider the personal sacrifices required of those who carry out the mission, as well as the emotional baggage hoisted by their families.

Chazelle holds back the release until very late in the film’s runtime when Armstrong and Aldrin finally arrive on the surface of the moon, a landscape rendered with an appropriately otherworldly quality achieved by shooting in a quarry with a 200,000-watt light. By the time Armstrong is ready to step from the platform, the mission has taken on a million meanings for those involved. But even as the visual splendor leaves the viewer in awe, Josh Singer’s screenplay undercuts the triumphant moment—the great human achievement—by suggesting that even the man who experienced it in the flesh was not elated by his accomplishment. It’s more of a consecration than a celebration, a sedate moment marked by stillness and contemplation, accompanied by ethereal theremin (courtesy of frequent Chazelle collaborator Justin Hurwitz) instead of a rousing score and cheers from crowds back on earth. While Armstrong never revealed how he spent his moments alone on the moon while Buzz Aldrin was off bouncing around in the lunar gravity—not even to his biographer, James Hansen, upon whose book the film is based—his cathartic visit to the Little West crater and the memento he leaves there provides fitting closure to the story; and it is capped off by an epilogue of equal gravity.

Chazelle’s technical control and contrarian approach to well worn subject matter give First Man a steady energy that suits its somber tone. It captures the wild reality that humanity sent a man to the moon with crude technology; and uses that fascinating story and its historical context as a platform to plumb the depths of the human spirit with an air of melancholia. It’s a testament to ingenuity, imagination, and perseverance, but also an extremely personal story about an emotionally-stunted man struggling to process his grief.

Sources:

Zhang, Jeffrey. “The Curious Case of First Man”. Strange Harbors. 19 November 2018.

Desowitz, Bill. “Beyond Christopher Nolan: ‘First Man’ Redefines In-Camera VFX”. IndieWire. 15 October 2018.