“I like libraries. It makes me feel comfortable and secure to have walls of words, beautiful and wise, all around me. I always feel better when I can see that there is something to hold back the shadows.”

Nine Princes in Amber is the first entry in Roger Zelazny’s lauded fantasy series, The Chronicles of Amber. Though the novel introduces some intriguing concepts, it is haphazardly written and reads like a rough draft from a freshman year creative writing course. I find myself unable to understand why it is held in such high regard.

Nine brothers battle for an inheritance left when their father disappeared, ultimately fighting for his vacant throne of Amber—the one true world, of which all others are merely shadows. The novel begins with our protagonist Corwin awakening in a medical care facility and suffering from retrograde amnesia. Like a fantasy version of The Bourne Identity, Corwin must discover who he is and why so many people wish him harm. He partially deduces his situation from the reactions of those around him, and bluffs his way into escaping from his drug-induced captivity. As he explores, his memory is jogged by his surroundings and conversations, and he gradually remembers his past and what he believes is his destiny.

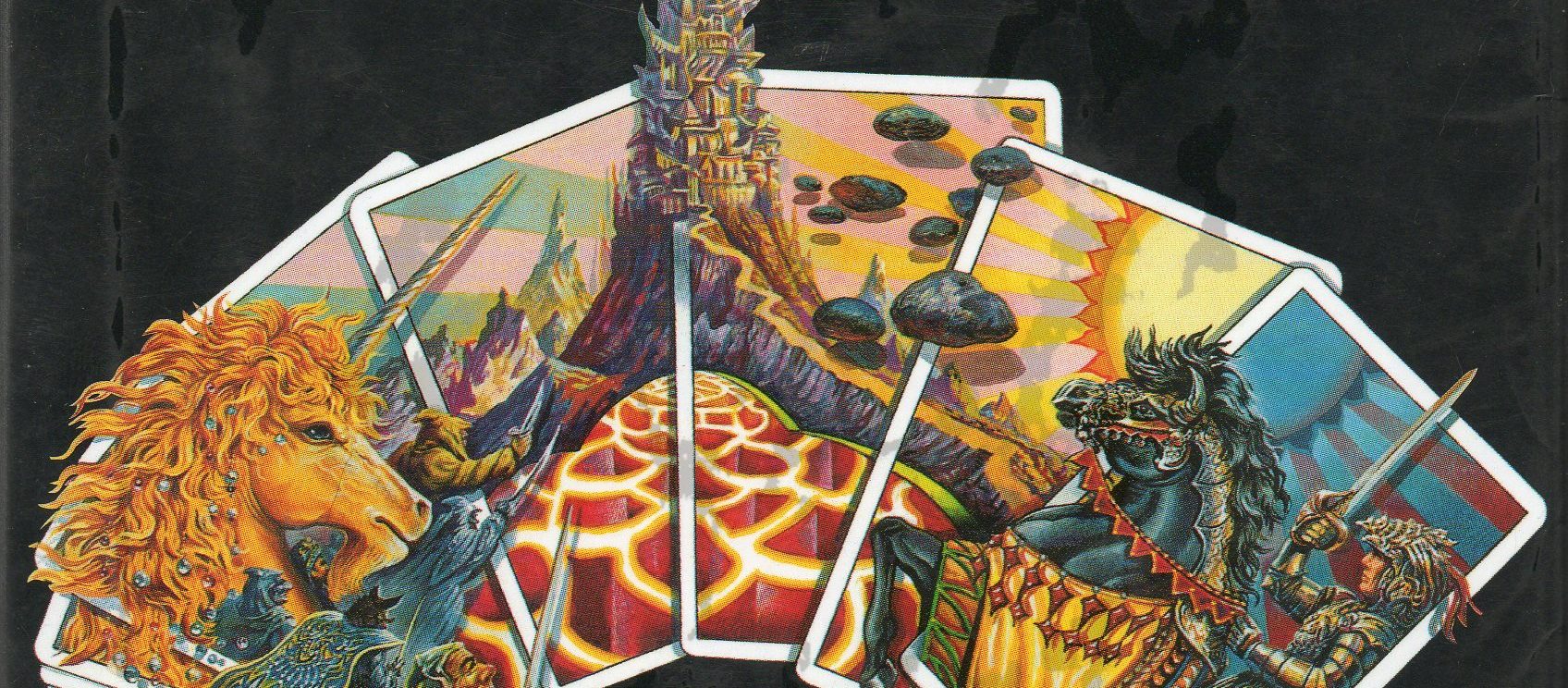

Within the first couple of chapters, he learns that he is a prince of Amber, which basically means he has godlike powers. He can create shadow worlds, communicate with his family members through a deck of tarot cards, and walk The Pattern—an intertwined, labyrinthine inscription which brings order to Amber. (One of the more engaging parts of the novel is when Corwin travels to Rebma, the undersea mirror image of Amber, to walk The Pattern there.) He is also an expert swordsman, can lift cars, etc. As he remembers his siblings, he has vague feelings about them—some he recalls fondly, but with others he shares a mutual animosity. His brother Eric plans to soon coronate himself as the new King of Amber, and Corwin launches an attack to make his own claim; some of his brothers join his side, others support Eric, and some choose to be uninvolved in the conflict.

In summary form, the general outline of the book has promise; but it fails to deliver on several different levels. Its first flaw is that it is simply too short. Corwin goes from blanking on his past, believing himself to be an ordinary man, to launching an assault with hundreds of thousands of warriors behind him in a matter of several dozen pages; the handling of the passage of time is plainly negligent. “I shall not bore you with repetition. My second year was pretty much like my first, with the same finale. Ditto for the third.” Corwin himself is only marginally developed; the other characters are all one dimensional, and Corwin’s half-remembered feelings towards them must be taken as sufficient reason for judging them the same way. This leads the reader to an uneasy ambivalence towards the main character which is at odds with the cocksure first person narration.

In addition to being too brief for its contents, as soon as the book should get really exciting, it completely falls flat. The latter half of the book is a long series of battles as Corwin makes his way toward Amber, but they are written like placeholders in a film script; or, to be pessimistic, like a toddler narrating an action figure battle. The world Zelazny created, while interesting, is severely undercooked, or at least unnecessarily vague. Beginning the book with a blank memory works well because then the reader must learn everything along with the protagonist. But Zelazny cheaply utilizes the tactic as Corwin simply remembers things when convenient, rather than discovering evidence of his past; like when he infiltrates Amber, and he is immediately able to escape detection.

I transferred myself to a hiding place I knew of within the palace. It was a windowless cubicle into which some light trickled from observation slits high overhead. I bolted its one sliding panel from the inside, dusted off a wooden bench set beside the wall, spread my cloak upon it and stretched out for a nap.

He also rarely questions anything that the reader would want to know in order to comprehend the mechanics of the book’s fantasy world. Compared to something like Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun, whose unreliable narrator is vague in the best way possible, Corwin recounts his story by emphasizing too many meaningless things while brushing over what should be the real meat of the novel.

So we fought on, and I was down to a hundred men.

Let’s be brief.

They killed everyone but me.

There are also mile-wide plot holes and contrived scenarios that are simply ridiculous. Corwin leads thousands of troops up a narrow staircase set into the side of a mountain. It is so narrow, and so treacherous to each side of the stairs that they must walk single file. And, on the way up, they are met by several thousand opposing forces coming down the stairs. Because of the narrow stairs, only two men may fight, one-on-one, until one of them dies. Then another replaces him. This goes on for hours. Corwin seemingly always has a pack of cigarettes stashed on his person, and always has a lighter (which works in Amber, even though gunpowder is inert there). It is never explained why Eric’s claim to the throne is less legitimate than Corwin’s, nor is much of anything elucidated, really. Granted, there are sequels that likely (at least I hope) explain more of the backstory, but the first book needs to be interesting enough that people would choose to read the sequels.

The book is written in a weird amalgam of outdated and posh language and casual slang. The linguistic mix is off putting, and really makes no sense considering the book’s internal logic. We go from “thee, “riposte,” and abundant thesaurus-speak, to “I dunno” and “he can cream us.” It could have been one or the other, but not both. Or maybe it could have been both but Zelazny just didn’t pull it off. There are a ton of needlessly awkward phrasings, and an over reliance varying forms of the bland “I did this thing.”

“Just curb your impetuosity in the future, when it involves life-taking in my presence.”

“I will,” he promised.

“Then let’s get rolling,” and we did.

Considering the slimness of Nine Princes in Amber, there is simply too much that is objectively bad to outweigh its positive attributes. An ambiguous and inconsistent magic system that is used as a deus ex machina; unclear character motivations; annoyingly careless dialogue; battle scenes that read like an accounting report; an overwhelming amount of dreck that must be waded through for a few neat ideas. It is really a shame because Zelazny has done good work elsewhere (This Immortal, Lord of Light), so he had to have known this was bunk. By most accounts, the sequels are better; but most accounts also think this book is good. It is not.