“I thought you said if we destroyed the brain it would die!”

“It worked in the movie!”

“Well, it ain’t working now, Frank!”

“You mean the movie lied?”

In what would amount to a minor conspiracy when set against the political mischief of modern times, the United States covered up the events depicted in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. In fact, the film itself was the coverup of a real military experiment gone awry: an attempt to chemically eradicate marijuana that led to corpses rising from their graves en masse.

All the undead bodies were rounded up and sealed in airtight military-grade barrels which were sequestered away in a secure location for safekeeping—except, of course, for the errant shipment of canisters that ended up in the possession of Uneeda Medical Supply in Louisville, Kentucky, where the contraband material has been secretly stashed and occasionally shown off as a spooky little sideshow for special guests. More than a decade after the initial outbreak, the bumbling night foreman at Uneeda decides to acquaint his new hire with the basement curio, and all hell breaks loose.

One of the metallic drums blows a gasket and unleashes a noxious brew into the air, knocking Frank (James Karen) and Freddy (Thom Mathews) unconscious. When they awaken, the carcass that was previously stewing in the barrel is mysteriously missing and a separate cadaver that had been chilling in the warehouse meat locker is now re-animated and hungry for brains. Along with their supervisor, Burt (Clu Gulager), they subdue the undead assailant and discover that Romero’s film was inaccurate—these zombies run, speak, think, operate machinery, dine exclusively on noggins, and cannot be killed by the standard headshot. They’re so resilient, in fact, with each individual limb and phalange continuing to squirm even after it’s been separated from its host, that Burt is compelled to ask his old mortician buddy Ernie (Don Calfa) to incinerate the writhing chunks of zombie that he and his employees have corralled into garbage bags. It’s a grisly but workable solution. The only problem is that the incinerator’s smokestack puffs toxic fumes up into the sky where they commingle with an oncoming storm and then come back down as acid rain, reanimating the deceased inhabitants of a nearby graveyard where a group of teenage punks have been loitering, dancing in the nude, and listening to rock music.

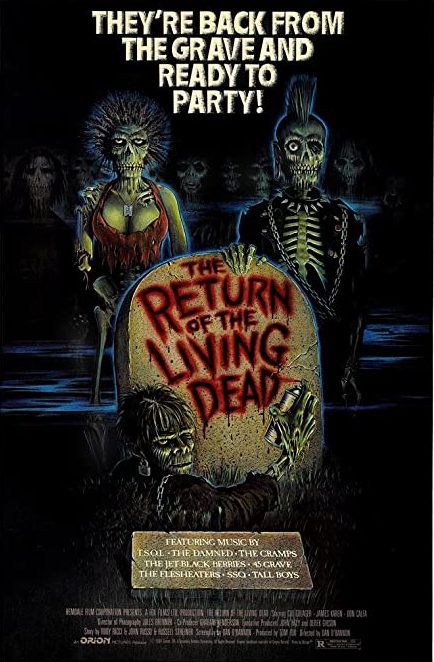

This is the gist of Dan O’Bannon’s The Return of the Living Dead, a delightful B movie made in the very spirit of bad taste. A mock sequel of Romero’s genre-defining hit, it began life as a novel by John Russo, Romero’s co-writer on Night of the Living Dead. The two would work together one more time, on Romero’s zombie-less There’s Always Vanilla, afterwards ceasing collaboration. However, after some legal mix-ups and the original film mistakenly slipping into the public domain, both Romero and Russo forged ahead with their own continuations. The same year that Romero released his first follow-up, Dawn of the Dead, Russo’s obscure novel was published, establishing his own legal ownership of the “Living Dead” franchise. Then, in the 1980s, as Romero developed into a cult figure, his lumbering flesh-eaters grew in popularity, and a subculture of zombie fanatics materialized, Russo sought to adapt his novel and capitalize on the cultural zeitgeist. Tobe Hooper was originally hired, but then changed his mind and decided to make Lifeforce—a film that was coincidentally written by Dan O’Bannon, who hopped into the driver’s seat on The Return of the Living Dead on the condition that he could rework the script to distinguish it from Romero’s films.

At the very least, we can attest that O’Bannon successfully put some distance between his film and those of Romero. Discarding all attempts at narrative sophistication, character development, or any other such nonessentials, The Return of the Living Dead leans into exploitation, absurdist humor, and effects-laden violence to carry a kitschy sendup of the genre. Consider that the very first zombie we encounter is pinned to the ground with a pick ax through the skull, then decapitated with a bone saw when he continues writhing around. Or that when we first meet Ernie he is listening to his Walkman and smoking a pipe while poking around in a fresh corpse; garbed in an apron and yellow rubber gloves, all stained with blood, his initial reaction when Burt taps his shoulder is to reach for the pistol he’s openly carrying in a hip holster. It’s this cheerful commitment to wacky nastiness that makes The Return of the Living Dead so endearing. Whether it’s the sadomasochistic Trash’s (Linnea Quigley) inability to regain her clothes after she takes them off for a nude dance routine atop a tomb (which has a humorous backstory if one is interested in behind-the-scenes tales about producers and directors butting heads), or the way the zombies call for backup paramedics then immediately devour their brains upon arrival, or the animatronic torso-and-entrails zombie that manages to hold a short conversation with its prey, or the midget zombie who launches an ambush, or the goopy costume of Tarman (Allan Trautman), or the bisected dog that comes back to life, or Frank and Freddy’s prolonged transition into an undead state—O’Bannon is constantly threading the needle to arrive in that bizarre realm where gross and amusing coincide.

But where many films that attempt to approach such territory lose their way and devolve into irredeemable messes, The Return of the Living Dead is upheld in various ways. Setting aside O’Bannon’s capable direction, the outstanding effects, the gutter punk style and soundtrack, and the furious editing from Robert Gordon—all of which elevate the material—I think the most undersung element here are the three performances from the older actors, Karen, Gulager, and Calfa. Though Karen is often asked to go hysterically over-the-top as Frank, numerous early scenes featuring these three are legitimately well acted. I particularly enjoy the sequence that introduces Ernie as it smoothly establishes the wily character and all his weird tics and mannerisms and allows the actors to lean into the story’s weirdness while still grounding it. Initially, Burt tells Ernie that it is rabid weasels squirming around in the bags, then requests that his old pal toss them in the incinerator. “You wanna burn them?” Ernie asks, incredulous. “That’s cruel! You just can’t burn animals alive. That’s just too hideous. Ew.” Then he pulls out his pistol and changes his tone. “At least let me kill ‘em first. Take ‘em out in the parking lot and put ‘em out of their misery.” It’s so absorbing that you may forget that you’re watching a low-budget horror flick. But even as these performances hold up under mild scrutiny, they’re shamelessly set against the wild and slimy grindhouse shenanigans. That’s the real draw of the film.

It’s possible to read The Return of the Living Dead in several ways: satire, nihilism, counterculture. But none of these lenses provides a view that adequately captures just how entertaining and lively it really is. Deceptively smart with its genre iterations and snappy dialogue, but dressed up in scuzzy, juvenile trappings, it is a true joy to behold; one of the inaugural and truly great horror-comedies. In cases like this, it’s of limited value to break down and analyze the film—just sit back, grab some popcorn, and have some fun.