“What we see and what we seem are but a dream, a dream within a dream.”

The opening images of Picnic at Hanging Rock depict the titular geological outcropping shifting in and out of a shroud of mist. It’s never shown in its entirety, and thus never set down as an objective location. Instead, these initial frames depict a kind of primordial force of nature that exists beyond the bounds of our modern understanding of the world; a living, changing entity that holds untold mysteries for those brave enough to explore its nebulous paths.

Long before the publication of Joan Lindsay’s book—upon which Peter Weir’s film is based—Hanging Rock was a center of life for the Aboriginal people; a place for commerce, spiritual rituals, ceremonies, fellowship. In the middle of the 19th century, the tribes who had occupied it for thousands of years were forced from it by European colonizers, the descendants of whom comprise the entire cast of characters in Picnic at Hanging Rock. However, although not a single Aboriginal appears on screen in the film, Weir, who would treat the Aboriginal way of life with such sincerity in The Last Wave, never pushes their mystical worldview to the wayside. Though cryptic, the film suggests, like Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout, that Aboriginal life is unsustainable in modern societies, and, likewise, that modern man cannot survive exposure to the wild Australian hinterlands where time dilates, rational thought fails, sequences of events blur together, and the world tilts off its axis.

A surprising number of human beings are without purpose. Though it is probable they are performing some function unknown to themselves.

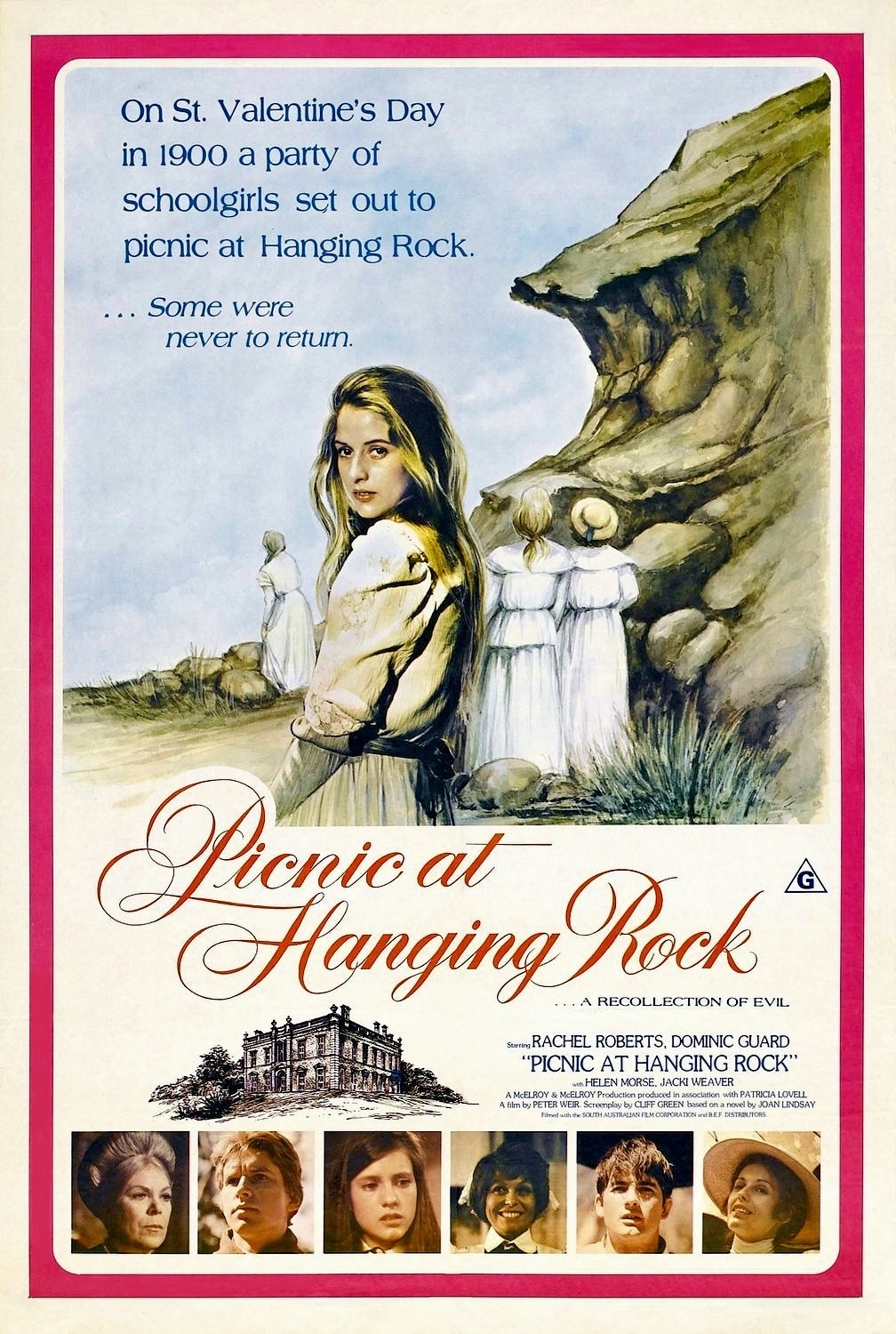

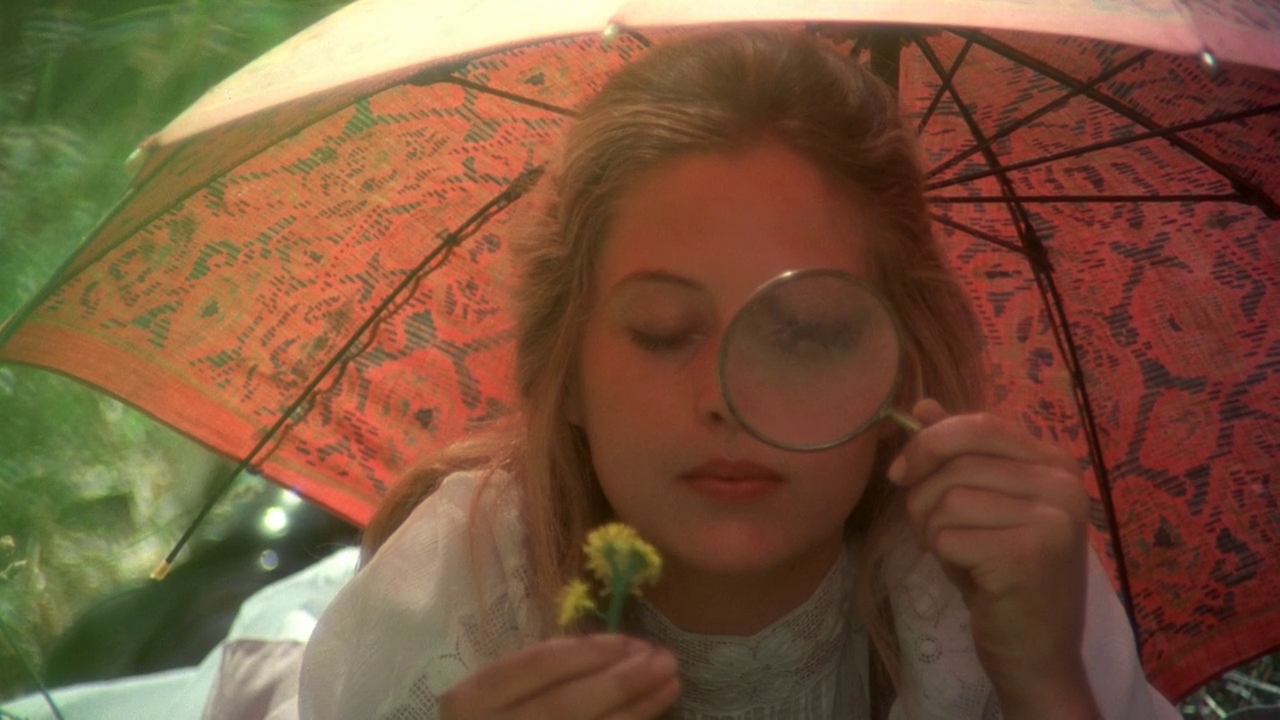

That is to say, when the four schoolgirls (Anne-Louise Lambert, Karen Robson, Christine Schuler, Jane Vallis) break from their boarding school peers during their daytime outing on St. Valentine’s Day in the year 1900, and begin climbing into the confusing maze of crags, you get the sense that they’re treading on sacred, magical ground. At one point, they even remove their shoes and stockings and continue their journey barefoot. Through impeccable sound design (including a wonderful mix of panpipe music, classical arrangements, choral chants, and long stretches of silence), breathtaking compositions, the recitation of poetry, and languid pacing, Weir presents the girls’ trancelike ascent as a spiritually transformative experience.

Another party—an older couple, their nephew, and their chauffeur—is placed in close proximity, not so that they can be viewed as suspects when three of the girls disappear without a trace (although, naturally, they are), but so that we understand that a trip to the place need not necessarily be accompanied by odd happenings. But even as the mundane threatens to take over in the form of a police investigation and a search for the missing girls, Weir strives to keep up the hypnotic rhythm generated by the opening segment, and to persuade the viewer to settle into a permanent mystery, to prefer the nagging discomfort of an impenetrable enigma instead of the objective conclusion that we naturally crave.

By dissuading the audience from speculating on the potentially grim realities of the disappearances, which undercuts the standard thrills that accompany ordinary mysteries, Picnic at Hanging Rock encourages the contemplation of more abstract themes. Now, to be sure, there’s a certain procedural quality to the story that prevents us from feeling entirely cheated. It’s not as if the girls disappear and their classmates and authority figures simply don’t care. No, there are certainly angles of approach. Perhaps the girls have fallen into a crevice, or been bitten by one of the reptilian creatures we’ve seen crawling across the rocks. Maybe the young Englishman (Dominic Guard) who followed the girls for a short while doesn’t tell a story that quite adds up. It might have something to do with the missing mathematics teacher, Miss McCraw (Vivean Gray), who was seen climbing up into the treacherous labyrinth clad in just her underwear. Or we also might suspect the stern headmistress, Mrs. Appleyard (Rachel Roberts), whose boarding school appears to be rapidly falling into financial ruin.

Even with these myriad strands of possibility, there’s an overriding sense that the girls’ disappearance is something preternatural, beyond our ability to understand. This notion is underscored by every creative choice, whether that be the ethereal glimmer of Russell Boyd’s cinematography achieved by draping a wedding veil over the camera; the barely-there characterizations and dazed mannerisms of the missing girls; the contrast between the orderliness of the school, where the girls’ self-expression is repressed, and the freedom of the outback, where hats and gloves and corsets come off; or the hazy description of the events. There are hints of themes: sexual awakening, passing from innocence into adulthood, premonition of predestined events, projection of subconscious desire, but the symbolism of the rock remains tantalizingly obscure. In that simple act of withholding resolution Weir and Lindsay leave us circling whatever ideas the shifty film has provoked in our own minds, none certain and thus none settled.

Picnic at Hanging Rock hones in on a haunting middle ground where neither rational nor supernatural explanations are sufficient to capture what we’ve experienced, where even the natural, common things like plantlife and seashells and lizards and birds and rock formations are infused with ancient magic. The horror, then, so singularly achieved, lies not in potentially learning what fate befell the girls, but in remaining in the dark, grasping at fragments and traces but never arriving at a coherent resolution.