“You look around at all the people and you realize you’re dealing with a government that’s failed everyone. All sides.”

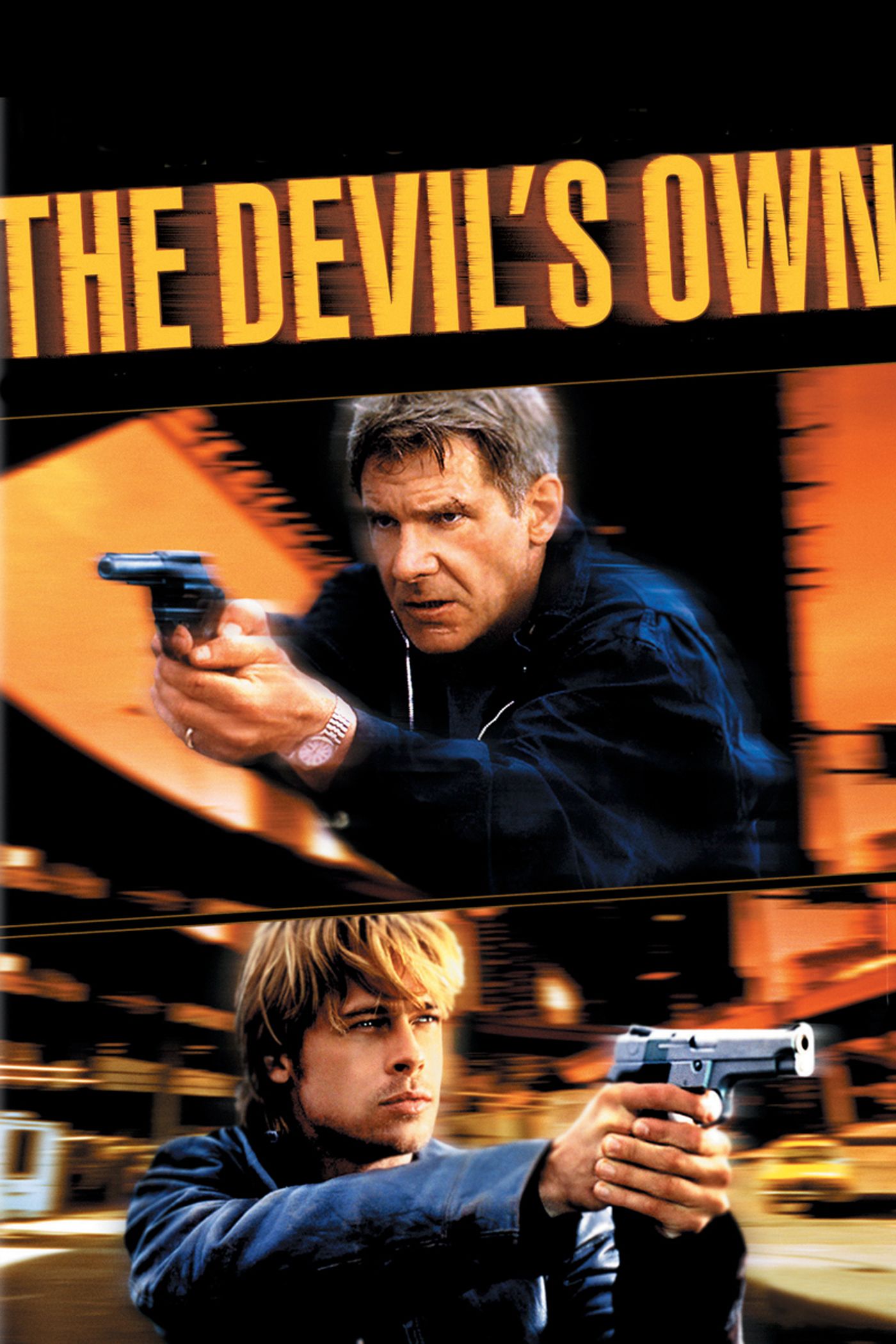

If it weren’t for the screen presence of its leads and compelling cinematography, The Devil’s Own would be a throwaway thriller. Such was not the case when Brad Pitt initially signed on to star in the production. Envisioning a gritty, low budget crime film that would intelligently explore The Troubles through the eyes of a wily IRA terrorist who comes to NYC to facilitate an arms deal, Pitt accepted a contract before a director was even attached to the project. Unfortunately, by the time the reigns had been passed into the hands of a fallen-from-grace Alan J. Pakula, the script had been rewritten so many times—each fresh polish pulling it further toward the generic—that there was no longer anything particularly compelling about it on paper.

The biggest pre-production hiccup seems to have been the addition of Harrison Ford, a huge box office name at the time, whose inclusion prompted an extensive, deleterious rewrite to increase his character’s role and make the film a co-starring feature. One could understand Pitt’s frustration with having a lead role on a long-gestating project morphed into a second-fiddle part next to a huge name like Ford, but his concern seems more fundamentally pointed at the rewritten script’s lack of coherence and significance. He had signed up for a film that was supposed to mean something, not a popcorn cop thriller. He threatened to quit part way through production and eventually spoke out against the film, calling it “the most irresponsible bit of film making—if you can even call it that—that I’ve ever seen.”

In hindsight, it’s not quite that bad, though it certainly trends toward the tasteless middle of the road where Pitt feared it was headed. Indeed, it’s so confused in its motivations that there’s almost no point in discussing it. Here’s the setup: Frankie McGuire is eight years old when his father is assassinated at the dining room table for being a suspected Irish republican sympathizer. This traumatic experience sets the young Frankie on an inevitable course. Twenty years later (and now played by Pitt), he is the charismatic leader of a lethal paramilitary unit in the IRA, and perhaps the most wanted man in Northern Ireland thanks to the impressive body count he’s accrued. Under an alias, Frankie travels to New York City to procure and arrange the transport of a shipment of Stinger missiles which will be used to shoot down British helicopters back in Ireland. For the duration of his stay, “Rory” lives on Staten Island in the basement of straight-laced NYPD officer Tom O’Meara (Ford) and his family. He grows quite fond of the O’Mearas, and begins to look to Tom as a kind of father figure. Why exactly Frankie had to stay with an unfamiliar American family is not entirely clear, let alone why his contact set him up under the roof of an intuitive cop who is bound to suspect him.

The film bides its time as Frankie ambles around New York, contacts other IRA members, has a brief fling with a courier (Natascha McElhone), makes inroads with an underground arms dealer (Treat Williams), etc. Meanwhile, Tom’s partner (Rubén Blades) shoots an unarmed burglar in the back, forcing the principled cop into a moral predicament that he sidesteps by simply retiring from the force. The two trajectories finally merge when Frankie tries to postpone payment on the missiles and the seller sends a hit squad to the O’Meara home to search for the money, a tense episode that nearly claims the lives of Tom and his wife (Margaret Colin) and immediately raises the cop’s suspicions. Once Tom forces Frankie to reveal his true identity and motives, an extended cat-and-mouse sequence brings the picture to a close.

Setting aside the fact that it woefully undershoots its original ambitions by failing to interrogate the larger conflict which sets its parameters, and that the story that eventually shook out of all those rewrites is shallow and generic and marked by fraying seams, The Devil’s Own is at least solidly constructed. Critics can say what they will about Pakula’s decline, but here, working with cinematographer Gordon Willis for the sixth and final time,1 he employs a simple and effective visual language that drives the movements of the story far better than the script itself. Indeed, the closer you look, the more intricate and visually compelling the compositions become, appreciably enhanced by skillful editing from Tom Rolf and Dennis Virkler. Of course, if you’re willing to look that far into it, the realization that Pakula and Willis are operating at a high level only exacerbates the issues with the underwhelming script, and we’re back to throwing our hands up in exasperation and just letting it run through its paces.

1. Pakula died in a car accident the year after The Devil’s Own was released and Willis never lensed another film before he too passed in 2014.

Sources:

Fisher, Ian. “Disaster? Was There a Disaster?”. The New York Times. 30 March 1997.