“No one can tell what goes on in between the person you were and the person you become. No one can chart that blue and lonely section of hell. There are no maps of the change. You just come out the other side. Or you don’t.”

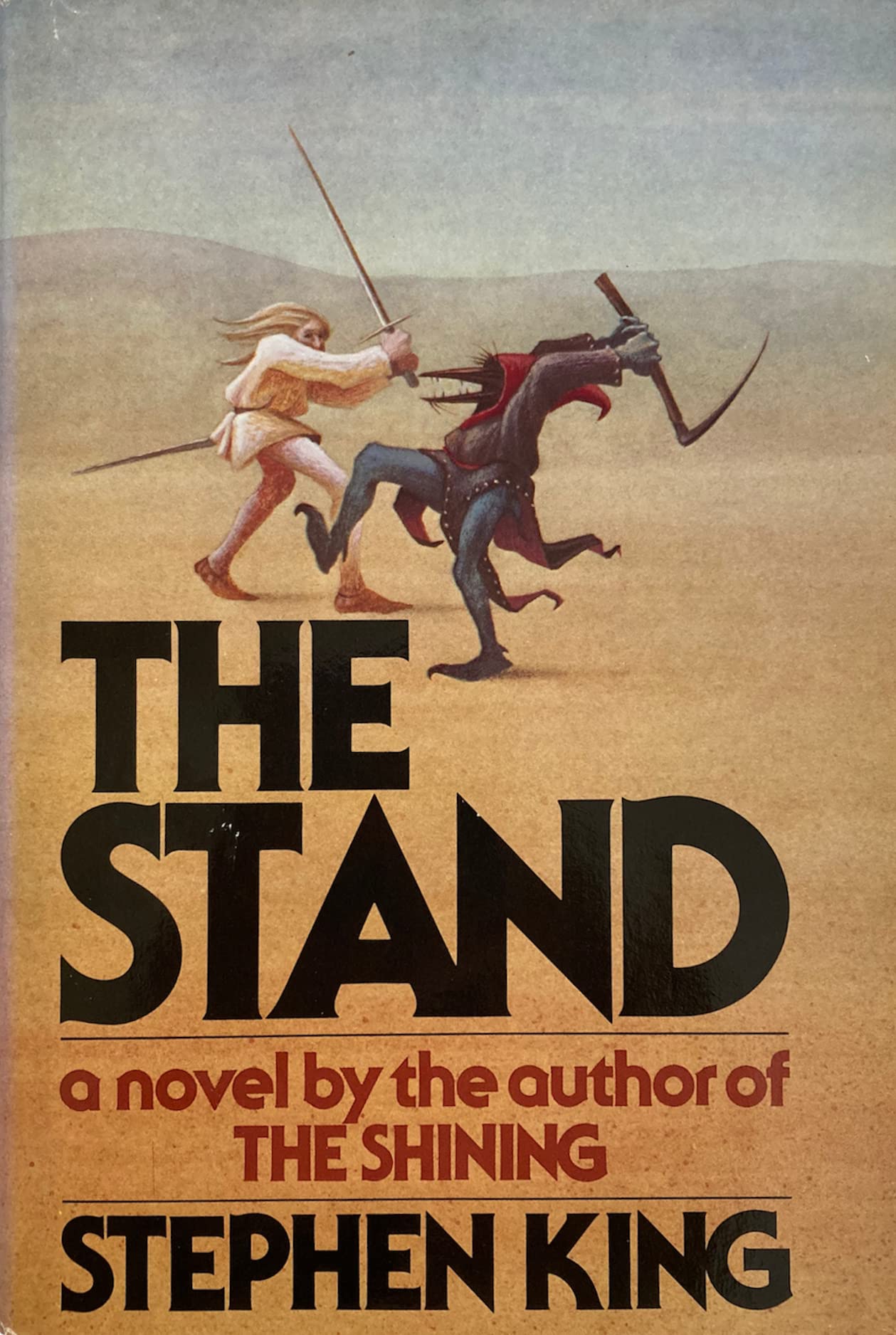

M-O-O-N. That spells ‘The Stand is the epitome of Stephen King’s Big Mac and fries style—tasty and addicting but lacking substance.’ Laws, yes!1 Perusing the web, you’ll find ardent fans of The Stand championing it as the best thing Stephen King has ever written. You’ll also come across detractors who take aim at its perceived offenses—misogyny, racism, exploitation of the disabled, etc. But there seem to be few readers (or at least few who publicly share their thoughts) who are neither enamored by King’s distended pulp apocalypse nor aggrieved by his choice of subject matter. I count myself among this minority latter camp, finding great appeal in the author’s richly drawn characters and post-society scenario but less than satisfied by his wobbly pacing, awkward handling of spiritual themes, and lazy climax.

(For what it’s worth, I read the “Complete and Uncut Edition” which, according to Wikipedia, contains approximately 400 pages that King had been forced by his publisher to excise from the original. It also updates the setting from 1980 to 1990.)

In The Stand, the United States government courts disaster by playing around with a biologically-weaponized version of the influenza virus in the confines of a lab setting. As became quite obvious for every citizen of earth in the wake of the COVID pandemic, tinkering around with infectious agents in a laboratory, especially to make them more deadly, is like playing with fire. Containment of the outbreak, as well as rapid vaccination attempts, utterly fail. Ninety-nine percent of the world’s human population is rapidly wiped out and society soon collapses. After burying their dead loved ones and loosely coming to grips with the situation, the survivors begin migrating toward central locations, their paths guided by recurring dreams of a wizened old black woman and a menacing shadow figure. The righteous-minded crowd gathers around the mystical Mother Abagail in Boulder, Colorado and tries to restart society by ratifying the Constitution, assigning public servant roles, getting the power plants back up and running, and so on and so forth. Over in Las Vegas, a ragtag band of evildoers coalesces under the vicious leadership of the preternaturally gifted Randall Flagg AKA the dark man AKA the walking dude.

“The Lord is my shepherd,” he recited softly. “I shall not want for nothing. He makes me lie down in the green pastures. He greases up my head with oil. He gives me kung-fu in the face of my enemies. Amen.”

Broken into three parts—the outbreak, the division into factions, and the collision of good and evil—The Stand is most successful in its early stage, which is perhaps to its detriment. In this initial section, King takes pains to flesh out his impressively large cast of characters as much if not more so than his premise. There are extraneous, one-scene characters strewn all over, of course, but it would be difficult to dismiss the author’s handful of main players outright. Larry Underwood, Stu Redman, Frannie Goldsmith, Harold Lauder, Nick Andros, Tom Cullen, Glen Batemen, “The Kid,” Judge Farris, Nadine Cross—I’m not going to say that all of these characters have terribly effective individual arcs (though several of them do), but each is drawn with sufficient clarity such that their personalities crucially affect the outcomes of various sequences and they attain a certain level of individuality. It’s the initial terror, when these characters must confront mental and emotional obstacles as often as they must contend with societal logistics, that the book is most affecting.

Considering that The Stand is over a thousand pages long (in the uncut version), it seems that the superflu is introduced too early and so the book peaks too early. But King doesn’t view the outbreak as his main source of conflict. Rather, he sees Randall Flagg, the embodiment of some demonic force, as his antagonist. By the time Flagg is properly introduced, perhaps more than a third of the way through the novel, King has already settled on a simple good vs. evil plot that gains its flavor less from its twists and turns than from its shifting perspective, relationships, and tangential ruminations on religion, spirituality, and abuse of power. In particular, I found the dynamic between Nick Andros, a deaf-mute, and Tom Cullen, a mental invalid, to be quite moving (and hardly exploitative).

However, setting aside the fact of a straightforward plot being couched inside of a mammoth tome, the most underwhelming aspect of The Stand is its circumvential ending which sidesteps the expected clash and shorthands the deliberate pace of the preceding thousand pages. The two sides are held at such a distance for the length of the novel that to have such a tangential touch be conclusive feels like a cop-out.

While I don’t think The Stand is an unassailable classic, it is a lengthy read that is nonetheless very easy to get through. There were dry patches here and there, but King’s conversational approach, macabre sensibilities, and well-imagined scenario provided sufficient hooks that I never flagged in my desire to finish the book.

1. For those who haven’t read the novel, the “M-O-O-N. That spells…” bit is a phrase repeatedly uttered by one of the characters in The Stand.