“Someone said television would produce a hundred million idiots.”

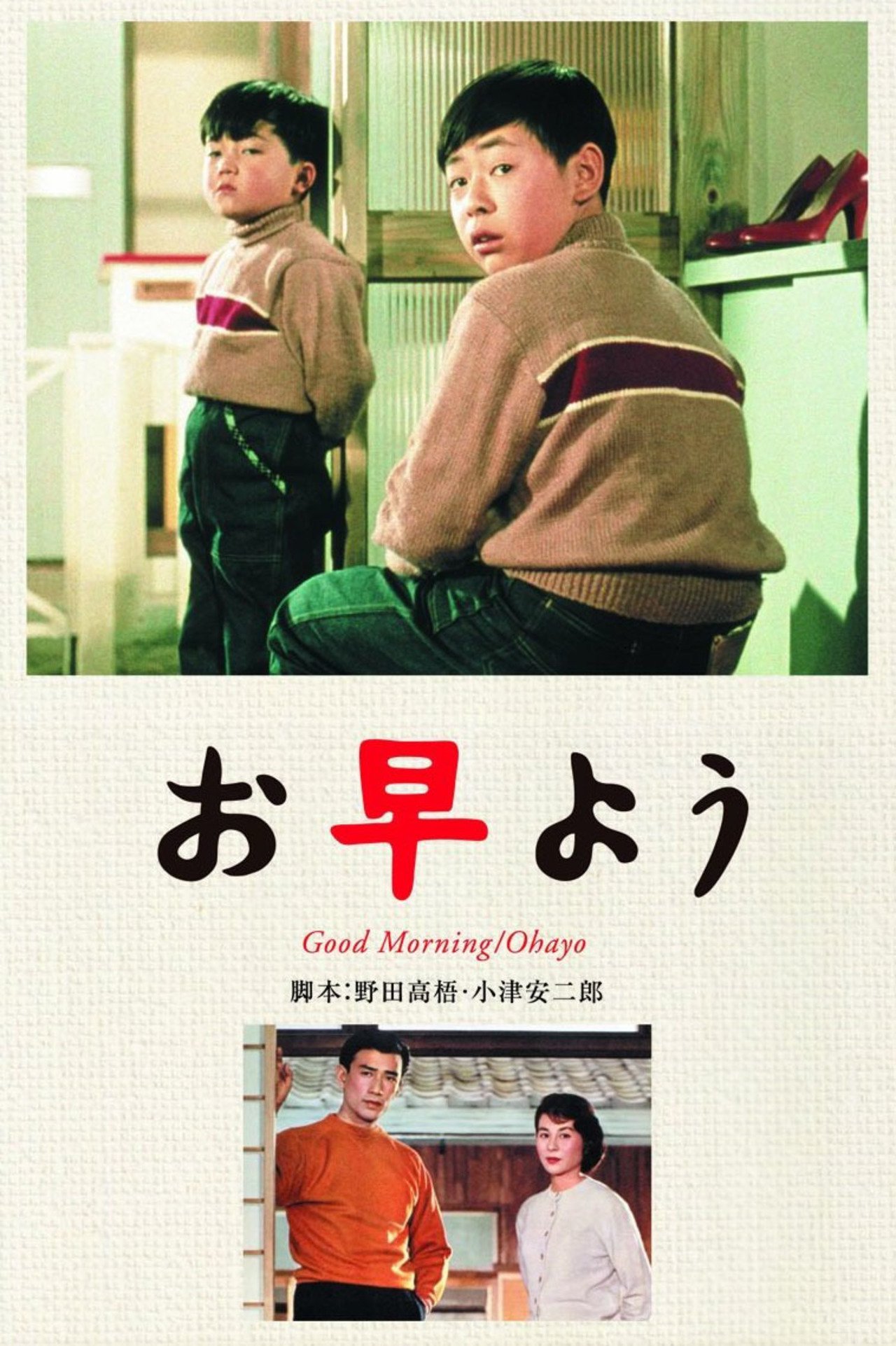

Yasujiro Ozu’s Good Morning is a remake of sorts of his earlier silent film, I Was Born, But…, that, on its surface, is a playful look into Japanese homelife circa the late 1950s. Shot in Ozu’s trademark style, with its knee-height camera placement, static frames, and ignorance of the 180 degree rule, it quickly establishes a cozy little rhythm as it sketches out the contours of its milieu.

Set in the Tokyo suburbs where a cluster of small domiciles has been crammed into a valley beneath powerline transmission towers, it centers on a pair of brothers who refuse to eat or speak in protest of their parents’ refusal to buy them a television set. It quickly spins up a lighthearted comedy of manners, an intriguing drama amongst the housewives, and a lowkey romance. While all of these have their charms, there’s a deeper level to the screenplay that goes beyond these low-hanging fruit to examine the changing traditions of youth, the interdependency that emerges in a community, the pitfalls of gossip, the profound necessity of small talk, and the ramifications of the encroachment of technology upon daily life. That the director is able to comment on such existentially challenging matters in a casual film that is replete with fart jokes is no small feat.

Good Morning consists in its entirety of a handful of modest, narratively simple, interlocking vignettes. The most prominent, possibly because of its unruly subjects, is the aforementioned hunger strike enacted by brothers Minoru (Shitara Koji) and Isamu (Masahiko Shimazu), who have become envious of their layabout neighbors and their television. Though the boys attend their regular classes at school—and have fun playing the Japanese version of “pull my finger” along the way—they skip their English lesson to sneak over and watch sumo wrestling.

Meanwhile, their mother, Tamiko Hayashi (Kuniko Miyake), an earnest and kindhearted woman, gets caught up in a silly misunderstanding involving the misplacement of the monthly dues for the local women’s club. It’s sorted out in quick order—Mrs. Hayashi did indeed deliver the money to Mrs. Haraguchi (Haruko Sugimura)—but the rumors that spiral out from this mix-up have outsized effects. On top of these two instigative situations, Ozu and co-writer Kōgo Noda build additional layers of miscommunication involving the boys’ tutor, Heichiro (Keiji Sada), who silently pines after their Aunt Setsuko (Yoshiko Kuga); the unemployed Tomizawa (Eijirô Tôno), who drowns his sorrows at the bar while lamenting about his inability to retire to Mr. Hiyashi (Chishū Ryū); and the pair of traveling salesmen who peddle their wares at each abode. The drama peaks when the two boys, unable to request lunch money due to their vow of silence, hungrily flee from home with rice and tea and give their family a scare when they do not return home by evening; they are found watching television at the station.

“Important things are difficult to say.”

“Whereas meaningless things are easy to say.”

Though Good Morning might feel inconsequential at first, what with its repetitive jokes about flatulence (there’s a sequence where the soundtrack is synced to exercise and a tuba sounds at the bottom of each squat), its chintzy xylophone music, and the endearingly silly performance from Masahiko Shimazu, to move on from it so easily is to miss its subtly rendered depth. Every minor action, exquisitely framed by Ozu’s patented still frames and penchant for right angles, deep focus, and long takes, is gradually spun into an interconnected web that describes all of the unspoken rules and social habits that guide family and community life. Consider the large embankment that reaches almost to the top of the frame and keeps our characters contained within their little village, a place where proximity and long familiarity mean that women may freely enter one another’s homes without accusations of trespass; where the purchase of a washing machine is newsworthy and an unmistakable sign of upward mobility. And yet, despite the proximity, many of these characters exist in distinct worlds due to their inability to communicate outside of specific circumstances: the boys alone in their bedroom, the men huddled together at the bar, the women gossiping in secrecy. But the two boys upset this balance with their request for a television. Their childish tantrum provides a humorous platform to explore the notion that technology-based consumerism is crowding out direct human interaction—a mode of engagement that is depicted as simultaneously wholesome and hollow.

As Minoru so aptly points out to his silently fuming father, even though adults talk a lot, they hardly say anything beyond banalities. The boys don’t understand the point, even as they trade their own empty gestures with their friends (their silly farting game). Why not just speak one’s mind? Their committed silence, in turn, forces the adults around them to consider the value of their idle chatter; to consider that all of this social lubrication must not be squandered, but should instead lead toward earnest discourse and fellowship. Their parents finally discuss retirement, their tutor and their aunt have a real conversation for the first time (even if they fail to find the right words), and the townswomen cease their petty gossiping. It takes a child’s mind to recognize the emptiness of most spoken communication, but, as they will discover, it is impossible to function without it. Good Morning, then, neither celebrates nor laments quotidian conversations, preferring instead to humorously ponder this most common aspect of the human condition.