“And it is told how once the earth swayed in deep quiet, swayed in deep silence, rested in stillness, softly rocking, and lay there, lonely and void.”

Abstract and nearly structureless, Werner Herzog’s Fata Morgana offers a perplexing, spellbinding meditation on the fallenness of mankind, the circle of life, and the transient nature of our earthly existence. It finds the director in a state of disillusionment, pessimistically examining his species, frustrated that every living thing is in a state of decay, but unable to entirely overlook the beauty of the natural world and simple human pleasures. It touches, however fleetingly, upon the mystery of our very existence.

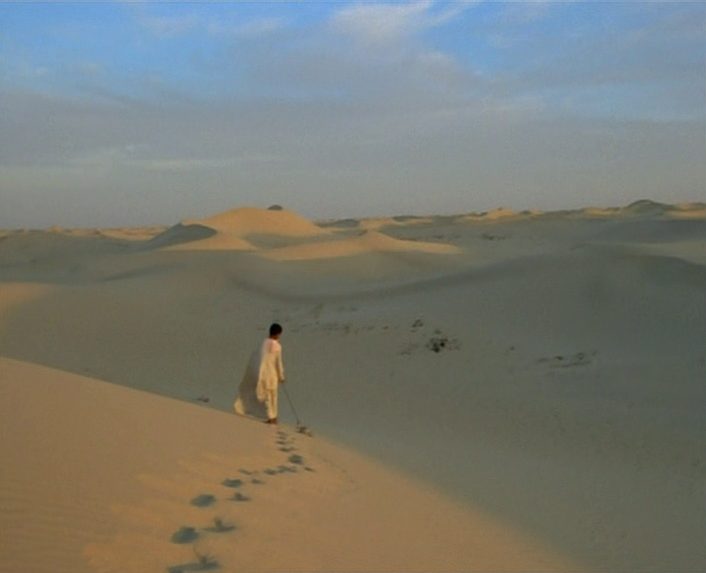

This stirring evocation is primarily achieved through inspired montage, juxtaposing decontextualized images—migrating birds, crashed vehicles, mirrored surfaces of lakes, the fiery chimneys of oil refineries, stray dogs, military tanks, barbed wire, dilapidated shacks, livestock carcasses, airplane wreckage, ragged children, expansive slums, a nuclear bomb test site—in such a way that it is impossible to form a coherent narrative around what we see, leaving us with images freed of dramatic intent and encouraging us to follow its vaguely associative clues. In this regard, it feels akin to Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi and Terrance Malick’s Knight of Cups. The overriding motif, the Fata Morgana or mirage, exemplifies the indistinct nature of the film, as we frequently see a hazy shape quivering on the far horizon but remain uncertain of its nature.

An interesting cross between documentary and fiction filmmaking, the project was originally intended to feature a science fiction narrative, wherein an alien species surveys a dying planet and concludes it is unsuitable for life. However, shortly after commencing filming, Herzog abandoned his screenplay in favor of simply observing the mesmeric desert mirages and primitive African societies of his setting, and cinematically contemplating the heady ideas that were weighing on him (and, judging by his subsequent output, still do). Then it took on a life of its own as he followed his muse into increasingly bizarre territory by interviewing subjects on inane subjects and showcasing off putting musical performances.

Even so, the director still claims it is a science fiction film. And the finished piece—filmed in 1968-69 but not released until 1971 as the filmmaker struggled to extract a narrative from the unfocused footage while he made Even Dwarfs Started Small—is so elusive and enigmatic with its expressionistic camerawork, narrated creation myth, absurd poetry, and eclectic musical selections, that its interpretations are numerous and varied. Objective images are thrown against mesmerizing illusions. Mozart collides with the acoustic ruminations of Leonard Cohen and African hymns. The detritus of modern industry is juxtaposed with primal culture. It’s cumulatively hypnotic, but the viewer must seriously engage with the film if they’re to take anything from it.

The film comprises three sardonically-titled chapters—Creation, Paradise, and The Golden Age. The first is the longest and the by far the most enchanting, consisting predominantly of tracking, panning, and static shots of desolate desert landscapes, sand dunes and mountains, that are entirely devoid of living things. There are no diegetic voices in this segment, only voiceover narration from film historian/critic Lotte Eisner (author of the seminal text on German Expressionism, The Haunted Screen) as she reads through a version of the Popol Vuh. More or less, the images match the spoken word here, as Eisner tells of the gods iterating on their design for humanity, only arriving at a version capable of communication on the third attempt. We see the vestigial remnants of a failed human society, but no humans. An unspoken suggestion looms, that perhaps additional tinkering is needed, that a fourth attempt to “get humanity right” might be in order, preceded by a wholesale termination of the current iteration.

The second segment begins as humanity starts to appear. It combines the music of Leonard Cohen with maybe-symbolic-maybe-nonsensical poetry as the camera takes in abandoned vehicles and rotting animal carcasses and a rudimentary human society and industry. Eventually, as the third chapter approaches, Herzog turns toward interviewing eccentrics who obsess over matters that the layman will consider exceedingly trivial. A researcher studies monitor lizards who can survive in the desert, a diver relays the attributes of a turtle, and so on. Perhaps this is meant as a comment on the impossibility of an individual knowing even a fraction of mankind’s accumulated knowledge. The film wraps up with much less majesty than it began, fizzling out without the poetry and mystique that marked its opening.

While profoundly moving in parts, I began to lose touch with Fata Morgana the longer it went. By the time Herzog was poking around in nightclubs and giving prominence to an avant garde duo performing a tasteless drum/kazoo/piano piece, it became clear that, just as the beguiling coherence of the earlier sequences was a fortuitous outcome borne of Herzog’s spontaneity, so that same lack of forethought undermined the latter portions of the film. Some would argue it is exactly that lack of premeditation that makes the film so abstract and entrancing. I could be persuaded to agree, but only insofar as that impulsive, instinctive filmmaking style had a hand in forming the earlier portion of the film.

Existing somewhere between the tone poem of Koyaanisqatsi and the intense focus on idiosyncratic human activity of Mondo Cane, Herzog’s film was initially claimed by stoners for its trippy qualities. But for Herzog, it has served as a sketching pad of ideas to which he’s returned throughout his career, albeit usually in a more conventional manner.