“Premonitions played tag in the grottoes of my mind, none of which I would have cared to take to lunch.”

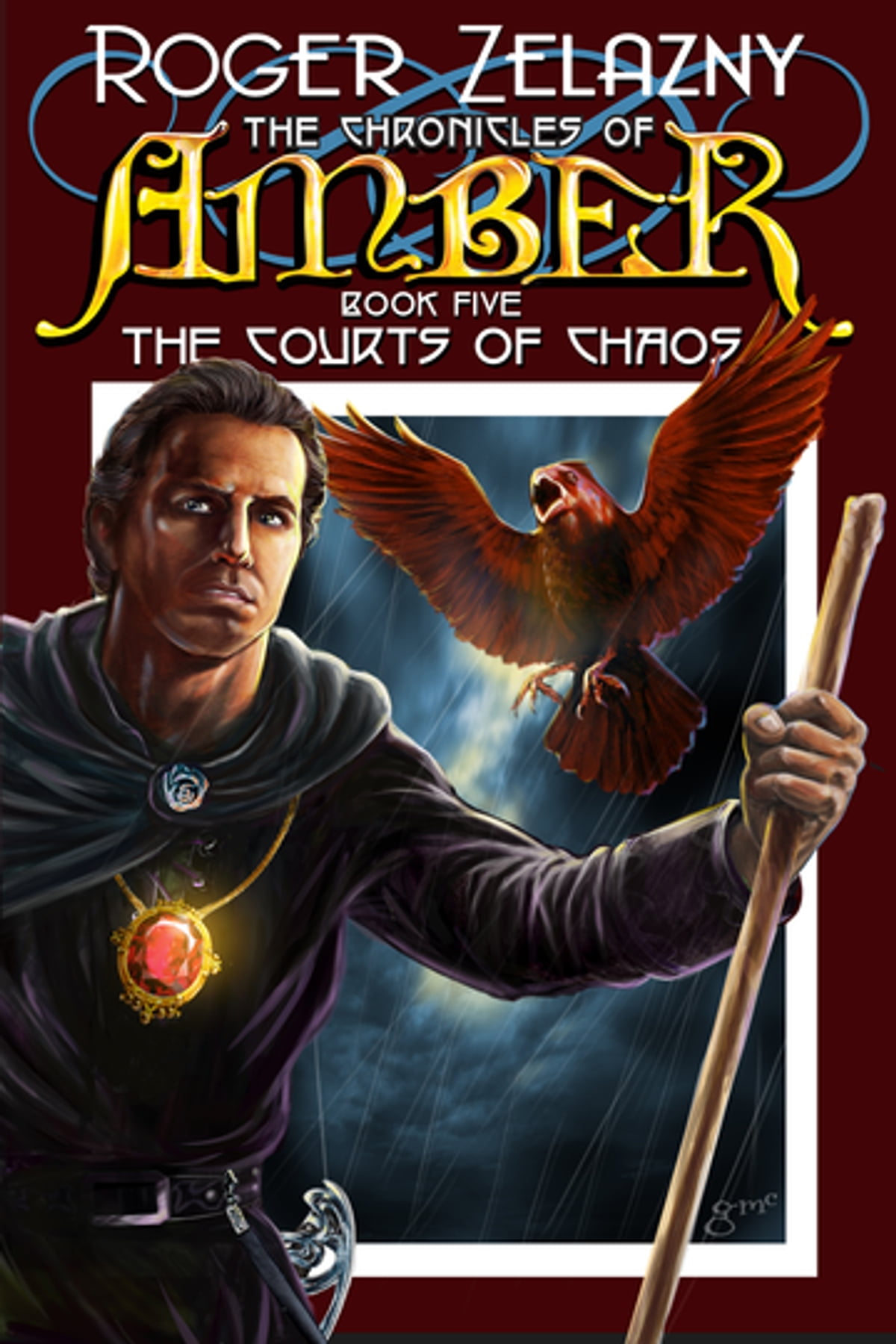

A mercifully slim volume, The Courts of Chaos brings the “Corwin Cycle” of Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber to a close by sending Corwin on an introspective, acid trip “hellride” toward the end of the world, carrying a magical artifact and accompanied by an inquisitive raven fashioned from his own blood.

When I read The Hand of Oberon, I thought it strange that Zelazny had used a large portion of the book to recap the first three novels in the series, given that each one is barely more than novella-length. Giving him the benefit of the doubt, I assumed that he was attempting to gather his frayed narrative into a stronger, more cohesive unit in order to prepare for an epic clash in the final installment. I was wrong. And given the enduring mediocrity of the preceding entries in the series, I should not have been surprised to find that this capstone is similarly digressive and unfocused.

In fact, the main story thread of The Courts of Chaos—Corwin’s contemplative journey with his bloodraven—is little more than a pointlessly meandering side quest that sees the cheeky protagonist travel through surreal shadow worlds where he encounters murderous leprechauns, a seductress, talking trees, a depressed giant, a treacherous jackal, zebra-striped skies, green suns, blood seas, and so on and so forth. Anyway, none of these deviations have any bearing on the main story, which involves Father Oberon’s background manipulations entering the foreground and his attempt to repair the damaged Pattern. After simply skipping a large chunk of this plotline in between books, this significant thread only resumes about two-thirds of the way through the final volume and ends in a soap-operatic anticlimax that keeps most of the main action off the page and involves a unicorn and the return of a character that had previously “died.”

I’ve occasionally referred to Robert Jordan as an “ideas guy,” and I think the same critique can be applied to Zelazny, though each author fails at conveying their ideas in written form in different, almost opposite ways. Jordan misses the forest for the trees by getting inexplicably hung up on inane details—say, the veins on the leaves, proverbially speaking—wrapping up his day’s work with excessive notes on a narrow subject and nothing else. When he finally sits down to piece together a novel, he includes all of it, no matter how unwieldy it makes the flow of his writing. Zelazny, on the other hand (still speaking proverbially), barely bothers with notes at all as he hacks away at a trunk here, prunes a few branches there; takes a soil sample here, kicks around some duff there; all the while scrawling shorthand in his field journal, his jottings marked by occasional wit and dark humor. Sometimes he’ll forget to write down something important and later he’ll just squeeze it in somewhere else, however ill-fitting. Thus, where Jordan’s work feels overstuffed with trivialities, Zelazny’s feels incomplete and scattershot, offering exquisitely intriguing tidbits along with its meaningless drivel. Taken altogether his messy style is marginally entertaining but in this case it is insufficient for a story of the proposed scope.