“I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry.”

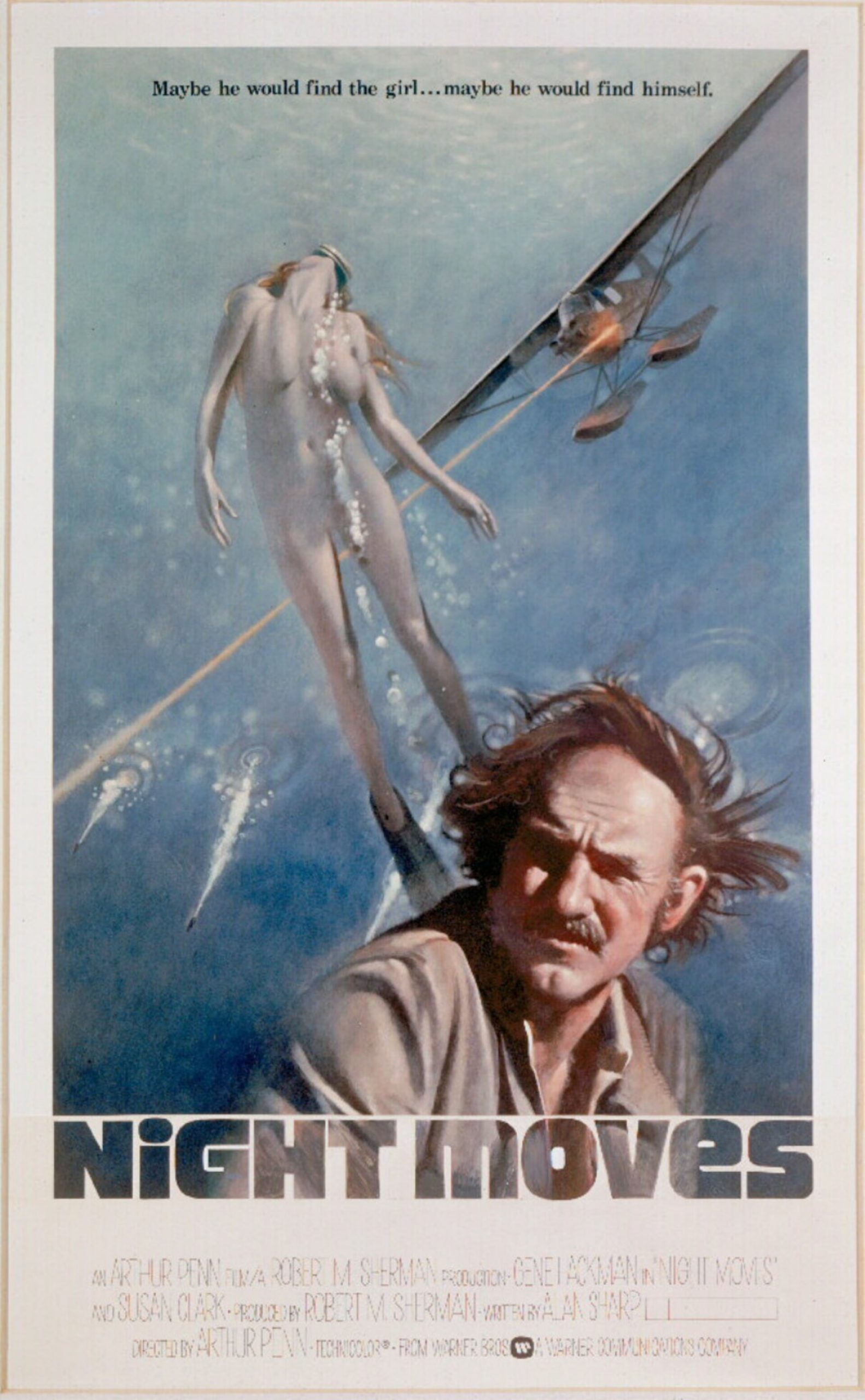

Night Moves is one of those enigmatic ‘70s films that shift and shimmer, that ostensibly adhere to a basic formula but ultimately shape themselves around the existential floundering of their richly drawn and deeply flawed characters, effectively revising their chosen genres. Think Coppola’s The Conversation, or McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye from Altman—all films that reflect the same senses of disillusionment and fatalism that pervade Arthur Penn’s neo-noir detective thriller. Indeed, the sordid individuals populating Penn’s film are so captivating in their dispirited pursuits and fleeting relations that they manage to elevate the film well above the erratic jags of its underlying plot.

Gene Hackman stars as Harry Moseby, a retired pro football player turned independent private eye who’s been hired by former B-movie starlet Arlene Iverson (Janet Ward) to track down her runaway daughter Delly (Melanie Griffith). But Harry’s burnt out, and not much of a gumshoe in the first place—a reality harshly brought home early in the film when he unintentionally discovers his wife (Susan Clark) engaging in a longstanding affair under his nose. “Who’s winning?” she asks upon returning home to find him listlessly staring at the fuzzy little television screen. “Nobody. One side is just losing slower than the other.” He is as incapable of untangling the threads of his wife’s infidelity as he is of parsing the web of intrigues that Alan Sharp’s screenplay bombards him with.

His two-pronged investigation quickly brings him into contact with Delly’s wiz mechanic ex-boyfriend Quentin (James Woods), a movie stuntman (Marv Ellman), a stunt coordinator (Edward Binns), and his wife’s lover (Harris Yulin). He hops from the mansions of Los Angeles to a movie set in New Mexico to the Florida Keys (great location diversity and mise en scène), where he finally finds Delly living with her stepfather Tom (John Crawford) and his girlfriend Paula (Jennifer Warren) in a cluster of hovels along the coast where they charter seaplanes and raise captive dolphins.

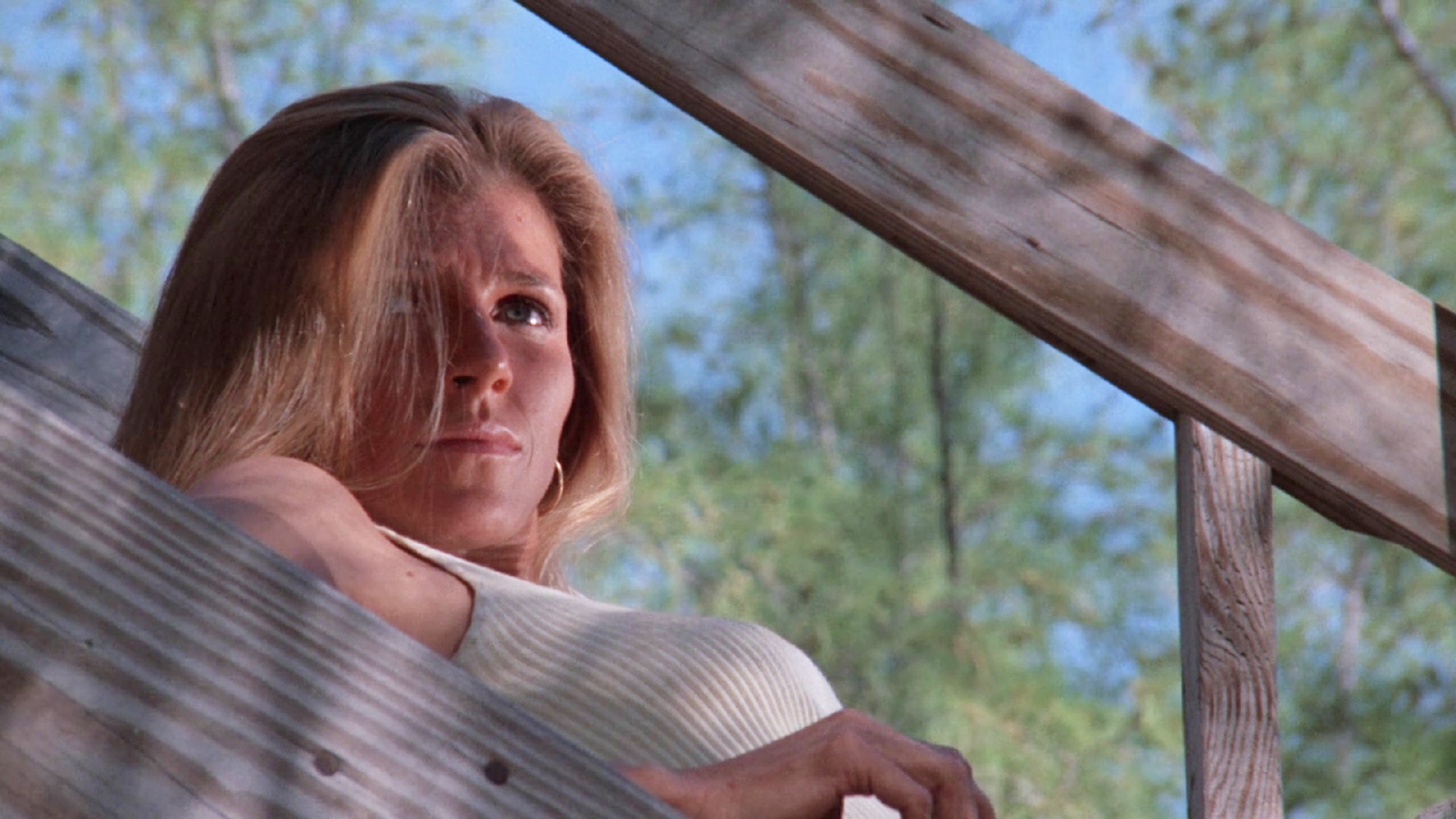

It’s here that Harry confirms that Delly has inherited her mother’s promiscuity—Tom happens to be only the latest in the rebellious conquest of Arlene’s ex-lovers. It’s also here that Harry proves out of his depth once again, as peripheral interests and a vague attraction to the façade of the trio’s modern living arrangement distract him from the larger mystery unfolding before his very eyes. Why does the discovery of a plane crash fundamentally alter Delly’s outlook on life? Why does Paula mark the spot with a buoy, then get drunk and seduce him that night? Why do so many people who should not know one another, know one another? Indeed, his awkward rumination over a historical chess match in which a champion player couldn’t think outside of the box and thus ceded the victory to his opponent serves as an apt metaphor for Harry’s own lack of intuition and obliviousness to his own incompetence; not to mention its underscoring of the chic post-Watergate cynicism that permeates the screenplay.

Paula: Where were you when Kennedy got shot?

Harry: Which Kennedy?

Paula: Any Kennedy.

It’s interesting to consider how the plot ricochets unpredictably, and yet how little that ping-ponging detracts from the film’s central exploration of Harry’s inner turmoil—a troubling mixture of professional failure, marital strife, and a haunting past. Even while we half-heartedly track the caroms of the labyrinthine plot, we hold it at a distance because we, like Harry, are not meant to catch onto its subterfuge. Essentially, he’s just acting the part of a private investigator while the scheme is playing out in plain sight. Thus we remain unbothered by the story’s background contrivances and unaffected by the mystery’s final solution. We liberally grant such leeway because the characters connect across the board. From Arlene’s vain silicone enhancements to Delly’s licentious pattern to Paula’s enticing coyness to Quentin’s evasive attitude, Harry finds himself surrounded by authentic if quirky characters, many of whom disrupt the flow because they are more than just narrative pawns. And Harry himself is perhaps the most lived-in of all the characters, with a sardonic outlook that finds him commenting on the quality of his home stereo system as he uses it to wake his wife and her lover in his own home.

But while Hackman turns in another superlative performance in a decade brimming with them—balancing a hardboiled toughness with emotional and physical fragility—for my money, it’s Griffith who provides the film’s anchoring performance, with Warren a close second. Her rambunctious inclinations firmly establish the gravitational effect Delly has on the other characters—including Harry, who initially seems bemused by her playful seductions but then finds his world’s gone topsy turvy when she’s involved in a car accident. After witnessing the young Griffith (fifteen or sixteen during filming), one understands why a stunt coordinator would remember the girlfriend of his mechanic visiting the set. It’s not quite expansive enough for a star-making turn, but it seems right that Delly grew up to play Lulu in Something Wild.

With its bevy of red herrings, blind alleys, and overall texture of ambiguity, some might dismiss Night Moves as the work of a confused storyteller. But there’s enough here on a textual level for both lowbrow thrills and more thoughtful engagement. While its surface can only be polished so much, its thematic reflections exhibit further depth on repeat viewings.