“Do something! Call me a cab!”

“Okay, you’re a cab.”

“Thanks a lot!”

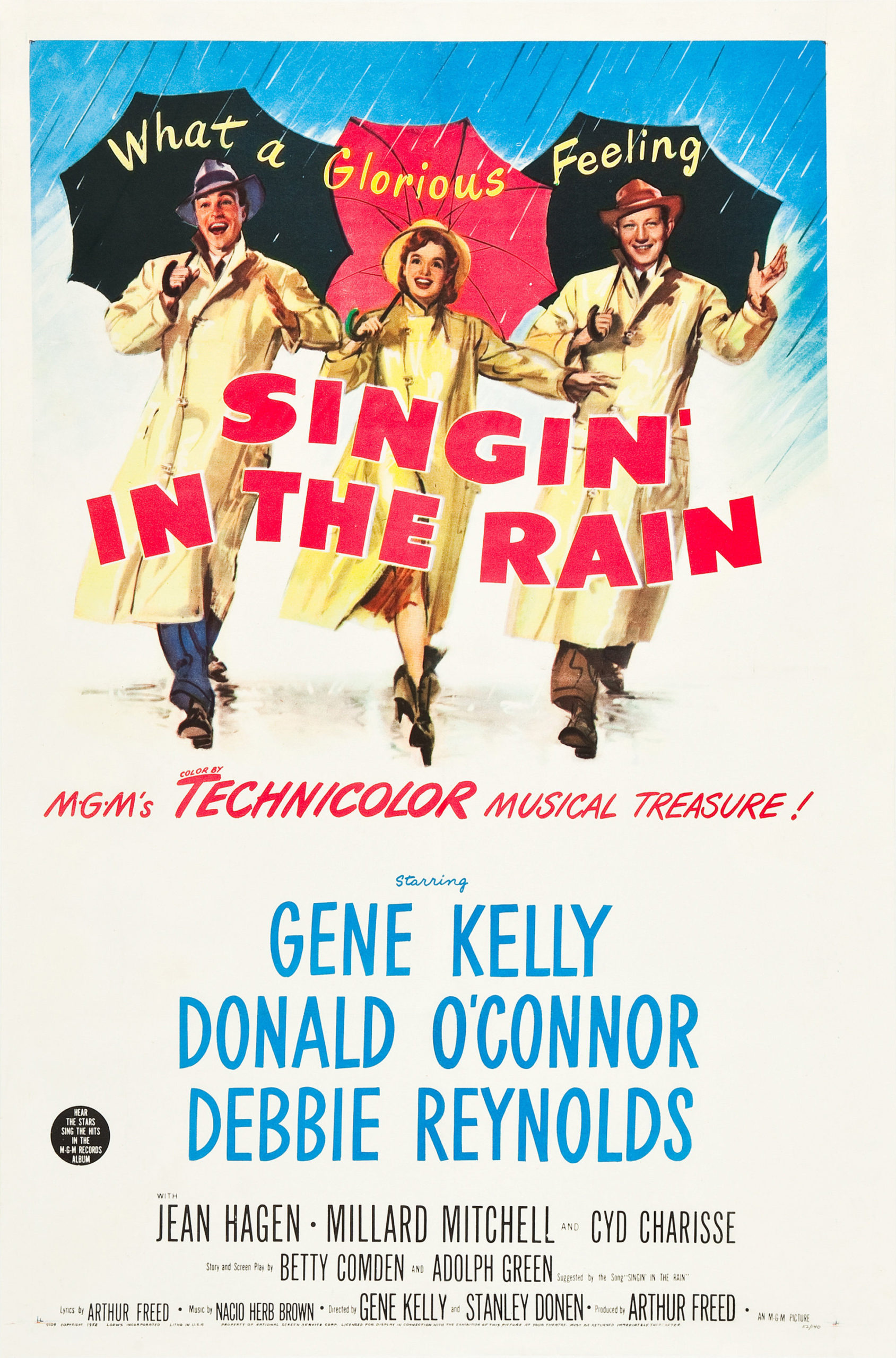

Singin’ in the Rain may be the greatest musical of all time, but not because it stands head and shoulders above its peers in terms of spectacle and choreography. Though it has eye-popping set pieces and balletic dance numbers strewn all across it, it is their integration into the text of a film that satirizes and celebrates the artifice of cinema that ultimately allows it to transcend its genre and become one of the greatest triumphs of Classical Hollywood, musical or otherwise. It’s a totally enchanting film, oozing charisma and joy out of every pore.

Gene Kelly (who co-directs along with Stanley Donen) stars as Don Lockwood, a popular actor caught up in the transition from silent films to the “talkies.” Having worked his way up as a vaudeville performer, tap dancer, and stuntman, Don can barely tolerate his narcissistic co-star Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), though he feigns romantic involvement with her to appease the studio’s publicity department. At the 1927 premiere of their latest silent swashbuckler, he stretches the truth when recounting his humble beginnings to a magazine reporter, dressing up his lowly exploits to make it sound as if he was always destined for the silver screen, always meant to be one half of “Lockwood & Lamont.”

After the show, while avoiding Lina, Don bumps into Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), an aspiring stage actress who scorns his profession even though she herself has deigned to leading a showgirl troupe—a revelation beautifully orchestrated when she pops out of a celebratory cake at the premiere’s afterparty and locks eyes with the actor. Of course Don and Kathy fall in love, but not without the airheaded Lina doing everything in her power to prevent it.

When Warner Bros. has a massive hit with their first talkie, The Jazz Singer, all of the other big studios quickly try to follow suit, and the next Lockwood/Lamont picture is reworked with a full script. The only hitch is that Lina Lamont, so well suited to the silent screen, has the voice of a toddler on helium and the diction of an unschooled New Yorker. Test audiences trash the film, owing to Lina’s hideous voice and a number of technical difficulties stemming from the inclusion of spoken dialogue. The solution, which strikes Don’s wingman Cosmo (Donald O’Connor) in a moment of inspiration, is to give the film a complete makeover, transforming it into a time-traveling musical and having Kathy overdub Lina’s vocal tracks.1

Where so many musicals are stiff and artificial, with actors breaking into song out of nowhere, cardboard characters, and plots that barely hang together, Singin’ in the Rain skirts these pitfalls by integrating its contrivances into a single coherent formula. Its show-stopping song and dance numbers are almost all worked into the screenplay with a fair amount of plausibility—a flashback to Don and Cosmo’s vaudeville days (‘Fit as a Fiddle’), Kathy’s performance with her troupe (‘All I Do Is Dream of You’), Cosmo’s attempt to cheer his buddy up (‘Make ‘Em Laugh’), Kathy’s supporting part in a flashy musical production, Don and Cosmo extrapolating their elocutionist’s tongue twister into a song (‘Moses Supposes’). These are not musical interludes; they’re built right into the story. And they’re so full of unfettered delight that it’s impossible to dismiss them, which is why many cite the film as the musical for those who don’t like musicals. Amazingly, most of these songs were written by producer Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown in the 1920s and ‘30s and cobbled into a coherent whole by screenwriters Adolph Green and Betty Comden and music director Roger Edens.

All of the actors have lovely singing voices and their in-sync dancing is superb, but Kelly and O’Connor are especially agile and energetic with their movements (Kelly also served as head choreographer). Kelly’s iconic rendition of ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ is understandably recognized as an all-time classic scene, yet it’s far from the only highlight here and maybe not even the most sublime. It’s certainly not the most breathtaking or funny; respectively, those honors would go to O’Connor’s astonishingly acrobatic performance of ‘Make ‘Em Laugh’, which finds the actor backflipping off of walls and excelling at a Keatonesque brand of physical comedy; and the pair’s jaunty take on ‘Moses Supposes’. The Russian squat dancing sequence in ‘Fit as a Fiddle’ is also quite an athletic feat.

There are many additional layers to Singin’ in the Rain—its inside baseball look at the filmmaking process and the product’s artifice (even while using that very artifice to impress you); its depiction of the transition from silent to sound film, and how that change simultaneously progressed and momentarily regressed the medium; the dreamlike stylizations of the ‘Broadway Melody’ and its relation to other artful blends of surreal ballet and cinema; the seamless integration of song and dance with narrative, such that they reinforce one another; the frequently brilliant script (“Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge… put together!” “I can’t make love to a bush!”); the way Kelly’s own upbringing provided inspiration for his character’s backstory. And I’ve scarcely mentioned Donen at all, the man whose storytelling sensibilities and technical knowhow provide a million little crucial details, like the fade from color to black and white or a choice decision to elevate a prop mishap into a brilliant exchange through canny editing. All of these pathways prove interesting to follow, but one only wants to explore them because of the hour and forty-three minutes of pure cinematic joy that they’ve just witnessed.

1. Ironically, in a movie that revels in highlighting the artifice of Hollywood filmmaking, Reynolds’ voice was partially overdubbed by an uncredited Betty Noyes.