“At least you get to go to Heaven. I don’t get shit.”

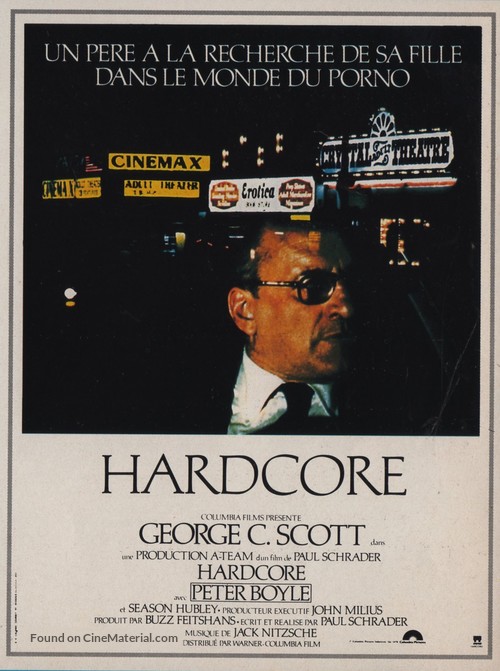

I was amused when in the opening scenes of Hardcore—a movie that explores the sleazy world of underground pornography and features a surplus of bare breasts—writer/director Paul Schrader threw in a reference to Pelagianism and even included biblical proof texts, traded by two men debating at the dining room table. By the time George C. Scott’s vengeful father finds himself explaining the finer points of TULIP to a cheap prostitute who’s helping him track down his runaway daughter, I was positively tickled pink. What a novel way to discuss a difficult subject that’s not often approached in mainstream cinema—juxtaposing a man who thinks sex is so unimportant that he doesn’t even do it, with a woman who thinks it’s so unimportant that she doesn’t care who she does it with. “And I thought I was fucked up,” Niki (Season Hubley) says after Jake Van Dorn’s (Scott) theology lesson.

Schrader follows this curious perpendicularity with a parallel between the hunter and his prey, depicting Jake as equally manipulative of women as the slimy pimp (Marc Alaimo) who cast Jake’s daughter Kristen (Ilah Davis) in a stag film. Even before Kristen disappears from her church youth convention in California, Jake is seen exerting his will over a woman he’s seemingly hired to spruce up the look of his dated wood furniture plant in Grand Rapids, Michigan, arguing over the shade of blue she has chosen. After hiring and then firing a sleazoid shamus (Peter Boyle) to track Kristen down, Jake takes it upon himself to sniff around the porn shops, massage parlors, strip clubs, and bordellos (shoutout to Tracy Walter, who turns up briefly as a night shift supervisor), eventually posing as a mustachioed smut peddler to get his foot in the door of the squalid industry (shoutout to Hal Williams as Big Dick Blaque). When he hires Niki to help him navigate California’s fleshpots, a peculiar father-daughter dynamic develops between them. But even as this relationship offers several insights, the viewer never shares in Niki’s hope that Jake might be her ticket to a new life. Indeed, the film’s anticlimax, which finds Kristen reluctantly going home with her controlling father and Niki returning to her old life, is not shocking at all.

Schrader looks back at his sophomore directorial effort with no small amount of derision, arguing that his writing was too blunt and his visual style bland and unsophisticated. He also dislikes the studio-imposed ending, which forced him to put Kristen back on screen when his original screenplay didn’t call for it. That meant Ilah Davis, chosen for her looks and willingness to shoot nude scenes, had to handle a scene with some dramatic weight to it. Schrader, perhaps annoyed by the forced change, shoots the whole thing with a certain detachment, and Davis is awkward and unconvincing. But this coincidental combination results in a narrative resolution that’s only skin deep—a thematically appropriate conclusion. Kristen decides to leave with her father, but does she really want to? How can these two return to their cloistered life after what they’ve each experienced?

Jim Hemphill does a bang-up job addressing Schrader’s criticisms, proposing that in almost every case the flaws that the director perceives are actually crucial to the film’s substantial stopping power. Schrader dislikes his static compositions, but they underscore the rigidity of Jake’s worldview. He takes issue with his explicit thematic rumination, but the contrasting worldviews are constantly subject to opposition and expansion. He detests his bold lighting schemes, and yet they give the film a sense of immediacy. They also provide just as much distinction between the film’s two settings as the contrast between Susan Raye’s ‘Precious Memories’ and Jack Nitzsche’s dark score or the detailed mise en scène with its church choirs, tobogganing, turkey carving, nudie mags, neon signage, “Jesus Is Coming and He’s Mad as Hell” fridge magnets, and Star Wars memorabilia. And even when it falls back on action tropes—the one element that’s universally criticized—there’s a symbolic elegance to Jake crashing through the thin walls of a bondage den, destroying the façade of intimacy promised by the tiny chambers.

Few films are simultaneously as overtly religious and willfully deviant as Hardcore, which sees Schrader torn between his austere Calvinist upbringing and the fascinating world of wanton sexual gratification; between the by-the-book strictures of religion and the amoral whimsies of secular culture. Unfortunately, Pauline Kael, upset that her protégé had made the jump from critic to artist, gave the film a scathing review that set a precedent for its critical standing.