“Everybody was peeing on my head and telling me it was raining.”

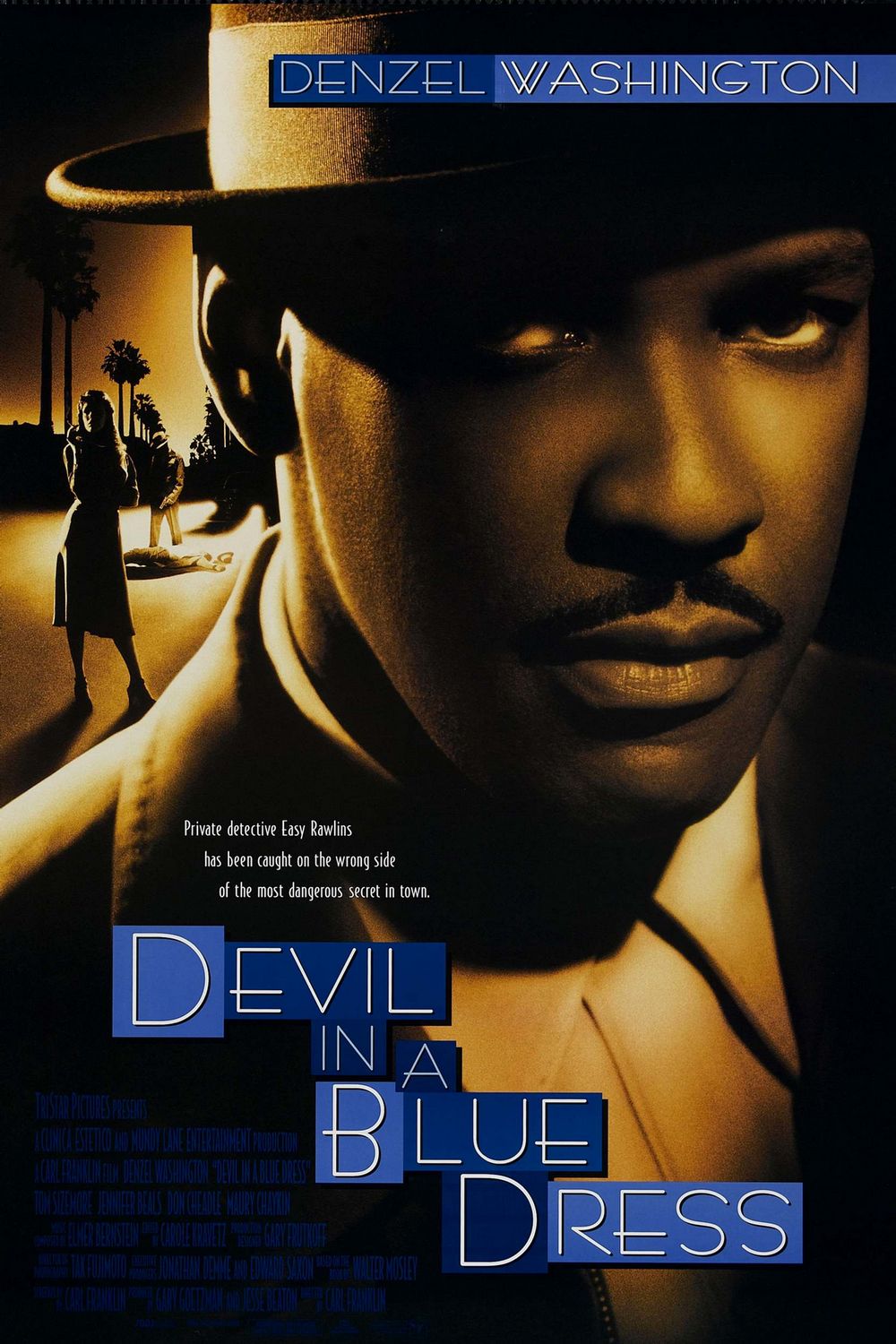

Laid off from his job at an aircraft assembly plant, WWII vet Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins (Denzel Washington) apprehensively accepts a gig as an amateur gumshoe under the aegis of shady operator DeWitt Albright (Tom Sizemore), an out-of-towner personally vouched for by a local bar owner and personal friend (Mel Winkler). Easy’s tasked with uncovering the whereabouts of Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals), the fiancée of a Los Angeles mayoral candidate (Terry Kinney) whose disappearance has caused a major disruption in the man’s campaign. In fact, it’s caused him to pull out of the race entirely. Word on the street is that Daphne, a white woman, has been frequenting the same juke joints that Easy favors; she may even favor “dark meat,” as Albright so crassly puts it. Though broadly apolitical and unskilled in detective work (making him something of a Hitchcockian everyman), Easy accepts the work because he needs to pay his mortgage. But the simple assignment soon spiderwebs into a diabolical tangle that sees the fledgling shamus navigating the strictures of 1940s Jim Crow etiquette and eventually cutting through them with the help of his psychopathic former wingman (Don Cheadle in a breakout role). Mistaken for the genuine article throughout his ordeal, Easy is inspired to hang his own shingle as a private detective.

Adapted to the screen from Walter Mosley’s first novel by director Carl Franklin, Devil in a Blue Dress is primarily a triumph of production design, performance, and theme. Set in 1948 Los Angeles, its period flavor is impeccable, from its atmospheric score (Elmer Bernstein) to its blues and jazz soundtrack (T-Bone Walker, Duke Ellington, Jimmy Witherspoon, Thelonius Monk, Memphis Slim), to its costumes and set decoration, all of it captured with verve by ace cinematographer Tak Fujimoto. Washington is by turns cautious and charismatic in the leading role, and his steady presence is complemented nicely by Sizemore’s sleazy shiftiness, Cheadle’s humorous predilection for senseless violence, and Beals’ sultry charm.

Mileage may vary on the film’s halfhearted embrace of the noir formula. On the one hand, it leans into many of the genre’s well worn tropes, including flashbacks, deliberate pacing, and excessive voiceover narration. On the other, it breaks from the mold by foregoing the shadowy aesthetics, giving us a sympathetic and somewhat decent leading man, and using its race relations backdrop for some unique plot developments. It’s at least half tribute with its buildup of dead bodies, blackmail, red herrings, crooked cops, smoking guns, and femme fatales, but beneath all that, or beyond it, it digs into subject matter that most films aiming at mainstream entertainment categorically avoid. Instead of giving the audience a cinematic illusion of depth that comes from a convoluted noir narrative, it offers a simple plot with great storytelling nuance, achieving legitimate depth by subtly foregrounding its subtext (meaning, of course, that it ceases to be subtext to some degree). Indeed, the crime of the film’s ostensible villain all but fades when set against the discovery of a certain character’s racial heritage. Maybe that unconventional storytelling focus is why it didn’t do much at the box office, despite Washington being only a few years removed from sterling performances in Malcolm X and Philadelphia.

As a baseline, then, Devil in a Blue Dress is eminently enjoyable, a stylishly made old school film noir with a novel storytelling angle. But at certain points it reveals hidden depths that indicate it might have more thematic meat on its bones than one had anticipated. I, for one, wouldn’t have minded seeing this turn into a series. Mosley’s written more than a dozen Easy Rawlins mysteries over the past thirty years, surely some studio would be willing to take a chance on it.