“I was just a living plaything that sometimes dared to rebel.”

Fantastic Planet begins with a totally familiar “pet” sequence: a young girl, upon discovering an orphaned creature next to its dead mother, asks her father if she can keep it. After an adhoc lecture on responsibility, he acquiesces. Tiwa brings the little critter home with her and names him Terr, and they quickly become the best of pals. She plays games with him, snuggles with him, dresses him up in funny looking costumes, and even lets him listen in while she’s doing lessons on her headset. It would be cute—and well, it kind of is anyway—if not for the fact that her tiny pet isn’t a bunny rabbit or a ferret, but a human being.

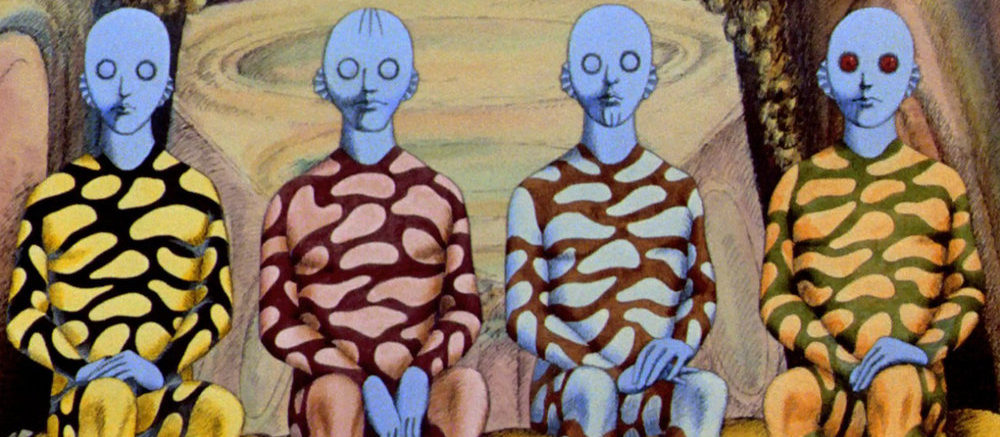

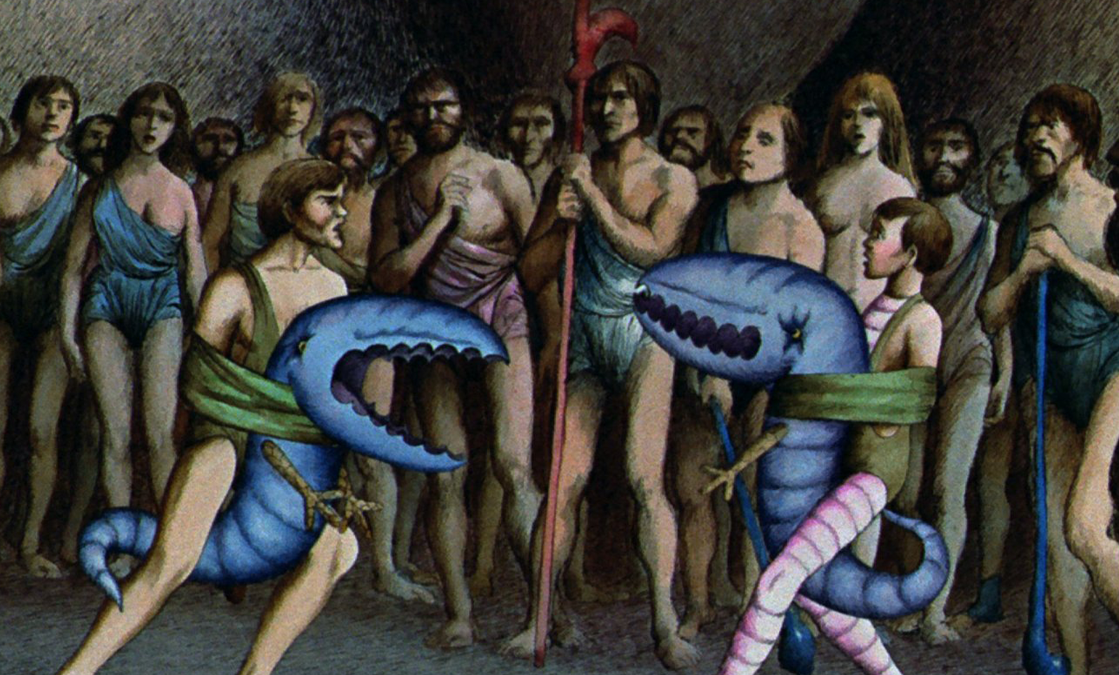

Set in a distant psychedelic future on a strange and exotic world, Fantastic Planet pits the Oms against the Traags—that is, the humans against the giant blue-skinned aliens that adorn most of the film’s promotional materials and inhabit the planet of Ygam. Living out his adolescence under the relatively peaceful care of Tiwa, Terr eventually grows into a headstrong youth. When his companion becomes mature enough to participate in the Traags’ mysterious out-of-body meditation ritual, and henceforth loses interest in him, he runs off into the surrealistic hinterlands of Ygam where he discovers creatures marvelous and strange, as well as a rather substantial community of “undomesticated” Oms with whom he collaborates to enact a plan for humanity’s escape from their overlords.

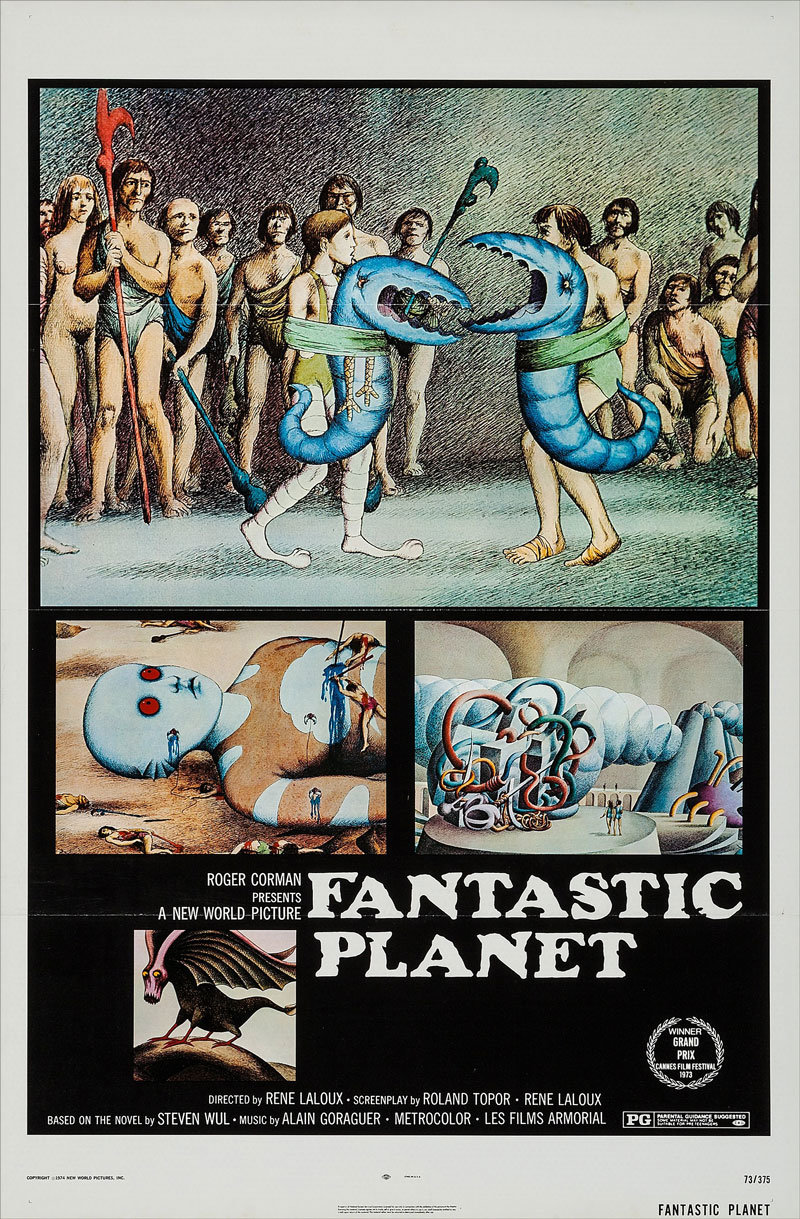

A summary of the parabolic narrative aligns Fantastic Planet with plenty of other dystopian science fiction stories. Indeed, it’s not too difficult to read it through any number of social lenses—genocide, slavery, post-colonialism, counter culture, xenobiology/botany, childhood, drug culture, oppression, animal cruelty, Cold War, technology—and lump it in with other similar apologues. But to reduce the film to its basic moral would sell it woefully short by completely overlooking its most compelling attributes, namely, its detailed alien world, its spiritual themes, and perhaps most importantly, its animation style.

Consider writer/director René Laloux and co-writer/artist Roland Topor’s cut-and-paste method. Reminiscent of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, it sees cutouts moving across painted backgrounds in a stop-motion pattern that renders as both oneiric and unnerving, giving the sensation of witnessing something truly alien that doesn’t quite square with the physical universe we inhabit (Alain Gorageur’s jazzy acid prog score, accented with woodwinds, wordless chanting, and saxaphone, helps too). The frozen facial features of the humans suit the material, suggesting that the Oms are indeed petrified in this world in which they are way down the food chain. Likewise, the art style fits the less familiar subject matter. The Traag technology is strange and inventive—gadgets that create portable storms, false shipping containers that devour anyone who tampers with them, and a slew of terrifying equipment used for eradication. Numerous weird beasts populate Ygam’s topography and are generally the stuff of nightmares, epitomized by either the phallic crustacean with too many eyeballs or the saw-toothed, bat-winged anteater that sucks Oms out of their hiding spots with a long sticky tongue. Even the harmless thread-effluviating critters appear plucked from the imagination of Hieronymus Bosch. Check out some of other unique flora and fauna at The Haunted Closet.

But it’s not all a grotesquerie. Certainly one of the reasons the film has gained a cult status is that despite its apparent simplicity, there is a depth in the Traags’ portrayal as a complex race with considerable communal and spiritual facets. Though their religious system is never explicated, its visual depiction—bodies morph, minds psychically mingle, astrally-projected avatars hover in bubbles—serves two purposes: first, to oppose the notion that they are totally villainous; second, to serve as a catalyst for the awakening of Terr’s consciousness. Indeed, without Terr’s education and formation alongside Tiwa, the Oms might never aspire to rise above their survival-of-the-fittest dynamic. Further still, this awakening of the mind uncovers a dormant spiritual aspect that is an essential component of the human condition. Even so, when the Oms encounter the mystical ritual that the Traags perform on Ygam’s orbiting moon, the scene implies a magic that the Oms cannot comprehend.

No matter which framework is applied to it, Fantastic Planet remains elusive in its interpretation, deftly deviating from its own throughlines with phantasmagoric set pieces, fanciful tangents, and a general reluctance to over explain its eccentricities. In the end, its meaning may be pliant, but that’s a feature rather than a bug, ensuring that those drawn to it will find something new to ruminate on each time they return. It doesn’t require an explicit meaning to be ceaselessly evocative.

The film had been on my radar for over a decade. When I finally watched it, I immediately watched it again, and I envision myself revisiting the landscapes of Ygam often, not to mention tracking down Laloux’s lesser known works. It’s one of the most purely imaginative films I’ve had the pleasure to see. As an added bonus, it was distributed in the U.S. by none other than Roger Corman’s New World Pictures.