“The real ones want their lives fictional, and the fictional ones want their lives real.”

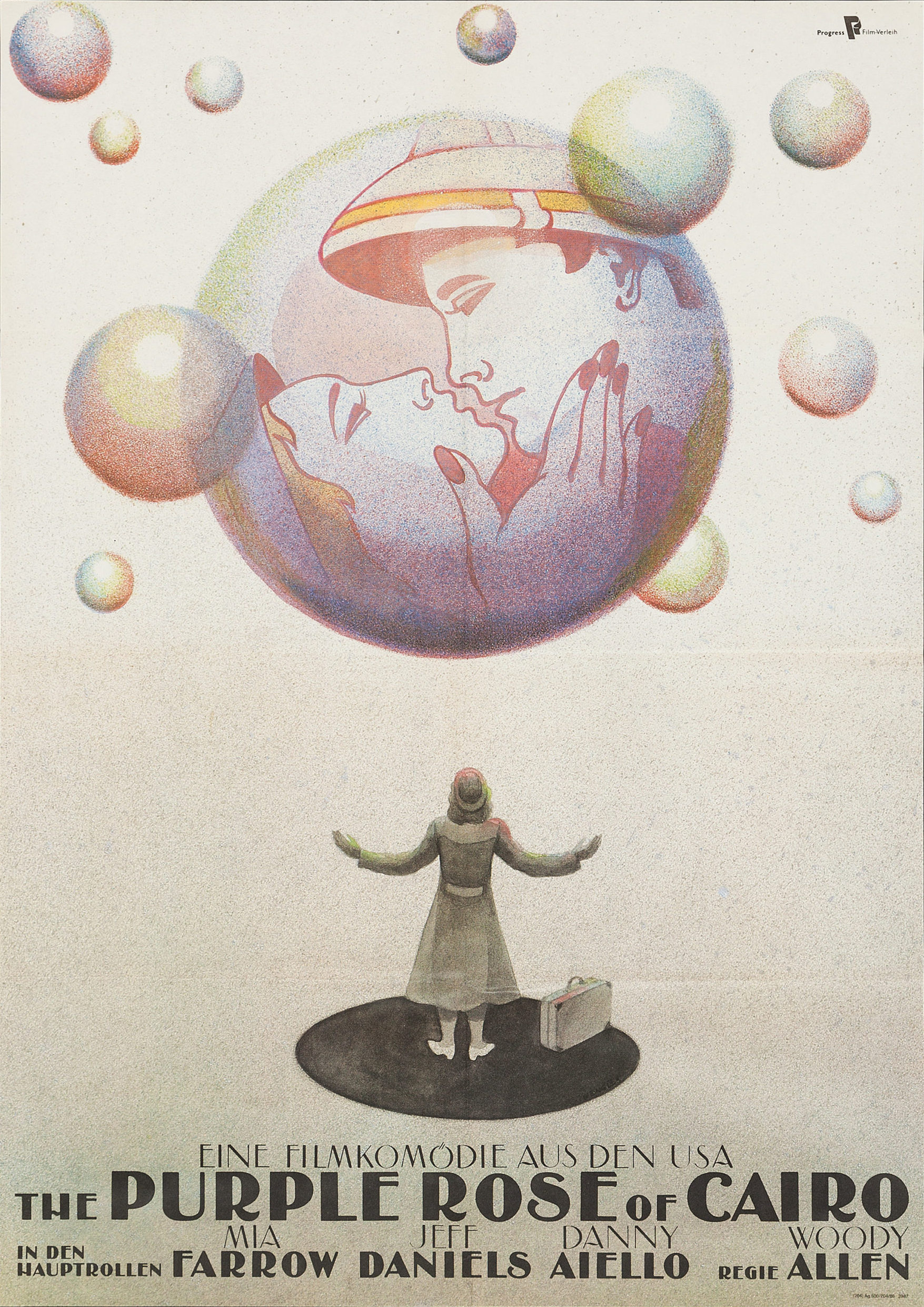

The Purple Rose of Cairo, a whimsical fantasy from Woody Allen, hangs upon a magical hook. When a Classical Hollywood movie star steps off the silver screen and into the theater to sweep an adoring fan off of her feet, her life and the movie industry are turned upside down.

Cecilia (Mia Farrow), a klutzy waitress in a loveless marriage to Monk (Danny Aiello), uses the movies to escape her circumstances, however fleetingly. Though money’s tight due to the Great Depression and her husband doesn’t seem to care much about finding steady employment, she finds herself repeatedly drawn to a new RKO picture starring Gil Shepherd (Jeff Daniels) as explorer/poet/adventurer Tom Baxter. She sees it so many times, in fact, that Tom Baxter finally recognizes his admirer and decides to walk out of the film to be with her. Things get complicated when Gil Shepherd comes to town to convince Baxter to re-enter the film, only to find himself similarly charmed by Cecilia. It develops into one of the most unconventional and delightful love triangles ever committed to celluloid—laced with comedic strands derived from the character’s incomplete personality and the disruption to the film he has left behind—that speaks to the notion of art’s therapeutic qualities.

It’s breezy and witty, imbued with charm by Daniels and Farrow, but there’s also considerable depth to it. The rules of the metaleptic excursion are made up as it goes along, and even disregarded at times, such as when Cecelia and Gil enter a music shop and begin playing and singing together, then re-enact one of Gil’s scenes from an earlier movie. Up until this point we’ve viewed Gil’s storyline as “real,” but here it takes on the texture and iconography of timeless cinema. Similarly, when Ceceilia follows Tom Baxter back into the black and white screen and together they craft a new narrative, their romantic evening takes on a familiar form.

When Tom visits a church and then a brothel, he’s confronted with things he doesn’t understand and soon becomes enlightened. “I stand in awe of existence,” he finally confesses to a flabbergasted prostitute, who simply cannot understand what it is like to be annihilated when the projector is turned off only to be resurrected for the next screening. Such marvels the real world holds—birth, death, sex, ferris wheels, popcorn! “Do you share my sense of wonderment at the very fabric of being?” This tension between the real and the imaginary worlds—Cecelia gives up her agency when she escapes into a movie just as Tom Baxter gains his when he escapes from one—provides The Purple Rose of Cairo with its bite, deftly capturing the transient euphoria that comes from dreaming ourselves into fantasies. Its bittersweet coda, unwelcome though it may be for the romantics among us, brilliantly underscores its themes.