“If you disobey the rules of society, they send you to prison. If you disobey the rules of the prison, they send you to us.”

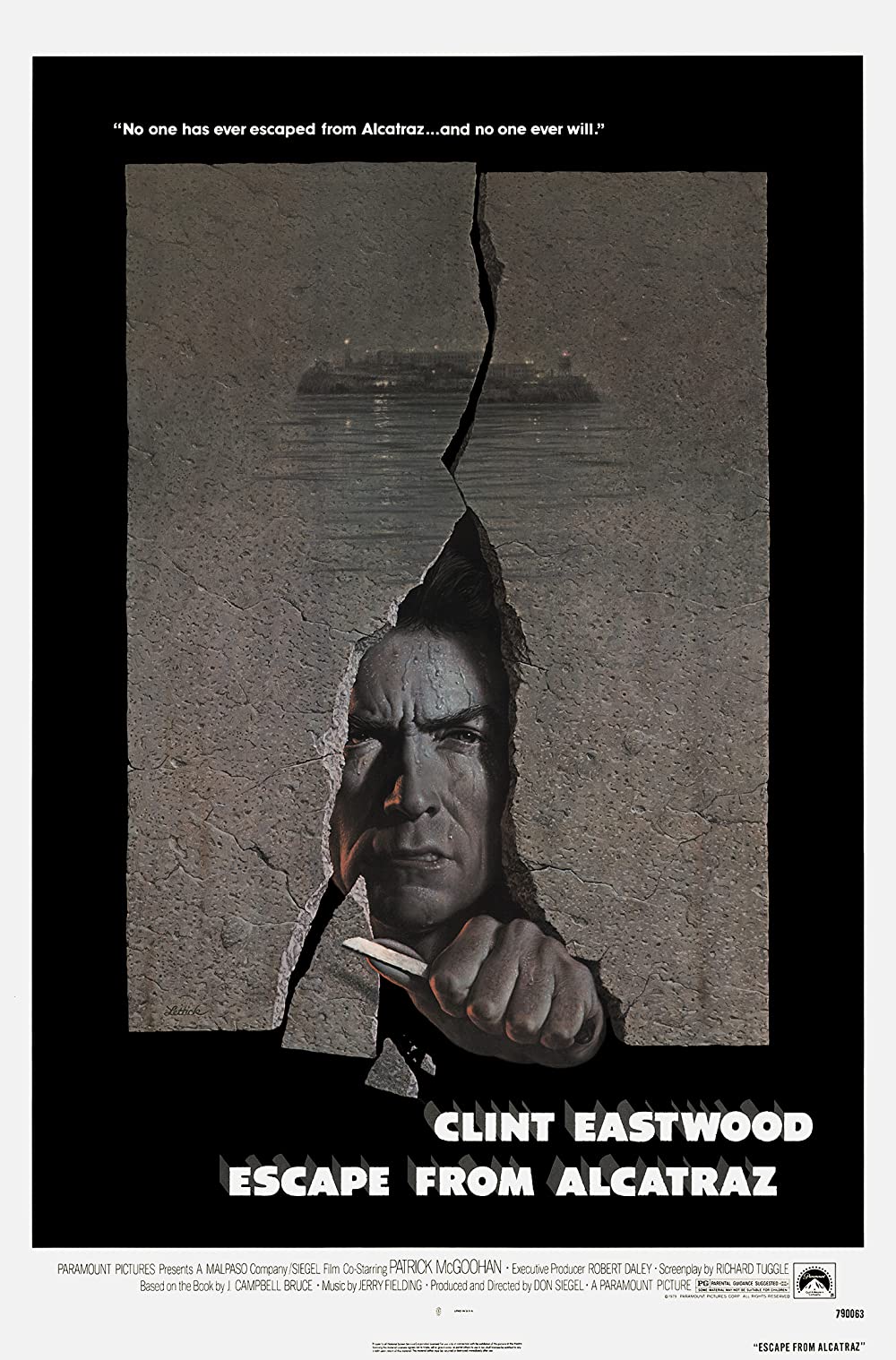

Filmed on site years after the federal penitentiary had been closed down, Escape from Alcatraz chronicles the real life breakout attempt of Frank Morris (Clint Eastwood) and brothers John (Fred Ward) and Clarence Anglin (Jack Thibeau); an attempt that was successful enough that authorities never recovered their likely drowned corpses.

Relying on the gloomy atmosphere lent by the location shoot, director Don Siegel crafts a taut thriller that hits all of the correct beats of the rich prison escape film tradition. Morris learns the rules quickly. Shave once a day, shower twice a week, haircut once a month. Don’t fight, don’t step out of line, don’t stand up for yourself. Books and magazines can be checked out from the library, but no newspapers. (Upon arrival, Morris humorously informs a news-starved inmate that his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers have moved to Los Angeles.) Morris meets the stern warden (Patrick McGoohan) and his scale model of the compound, filching a set of nail clippers from his desk which will be used to chip away at the aged concrete cell wall. He makes friends with a lifer librarian (Paul Benjamin), an eccentric painter (Roberts Blossom), and a well-connected old-timer (Frank Ronzio) and his pet mouse; and makes enemies with a sexual predator (Bruce M. Fischer). We get a sense of the overall monotony of prison life and come to understand the existential dread that would accompany a life sentence. Cruel treatment toward himself and others crystallizes Morris’s decision to mount an escape, and the arrival of his old pals the Anglin brothers, as well as car thief Charley Butts (Larry Hankin), sets the plan in motion.

In contrast to The Shawshank Redemption, which takes the basic blueprint of Escape from Alcatraz and squeezes it for all of the pathos its worth, Siegel employs a visual storytelling technique that speaks volumes without the need to bring it all out into the open with dialogue (which, of course, meshes perfectly with Eastwood’s laconic demeanor). It verges on overt sentimentalism a few times—when several inmates visit with loved ones separated by glass panes, when a flower symbolizing the human spirit is thrown on the cafeteria floor by the warden—but the emotional and spiritual burdens that these men carry are generally conveyed via well considered implication. If the lack of backstory and ambiguous conclusion sap some of its dramatic power, it certainly remains a very fine tactical prison break film in the mold of The Great Escape.