“Sometimes a blind pig finds a truffle.”

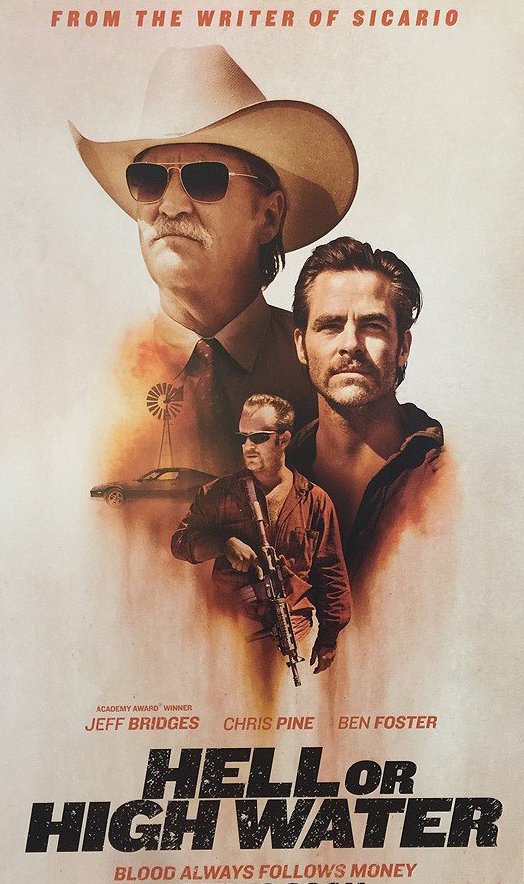

I’m not sure if it ever coalesces into something greater than a sum of its parts, but David Mackenzie’s neo-Western Hell or High Water is a resounding triumph for many of the individual talents involved.

Ben Foster and Chris Pine play a pair of brothers born into generational poverty who decide, upon the former’s release from prison, to carry out a string of small-scale robberies to save the family’s ranch and set the latter’s children up for a better future. Within just a few scenes primarily dedicated to tense action, we glean the gist of the brothers’ desperate situation—which certainly involves the Texas Midlands Bank whose various small town branches serve as their primary targets—and come to see the uneasy alliance between them. Toby (Pine), the level-headed mastermind of the operation, wants to follow a carefully laid plan, while Tanner (Foster), a loose cannon devil-may-care type, would prefer to fly by the seat of his pants.

But even though Tanner’s wild amorality helps to humanize Toby, Taylor Sheridan’s smart screenplay deliberately undercuts the romantic outlaw mystique that usually shakes out of such narrative arrangements. To wit, in an interlude, Toby confesses to his teenage son that the things he will hear on the news about his father and uncle are indeed true, and that he should take heed and not follow in their footsteps. After seeing the thing through and saving the ranch, his ex-wife and kids live there while he rents a small apartment in town.

Though the opposing characters don’t actually meet until the film’s coda, set against the brothers are Texas Rangers Marcus (Jeff Bridges) and Alberto (Gil Birmingham). If the interplay between the brothers is marked by realism and observational insight, the Rangers’ dynamic is positively Coenesque, overloaded with regional flavor, character quirks, and interpersonal tension stemming from the elder Ranger’s ingrained racism. A scene where the pair gets tripped up ordering at a steakhouse is a particular delight.

Since the Rangers don’t actually cross paths with the criminals until the finale, their entire arc is given over to exploring their odd couple relationship. Bridges gets the lion’s share of the juicy dialogue (“He wouldn’t know God if he crawled up his pant leg and bit him on the pecker.” “Now that looks like a man who could foreclose on a house.” “Let’s get some giddy-up music going on there.”) in what largely feels like a rehash of his ornery Rooster Cogburn schtick from the Coen’s True Grit, but an intense scene near the end of the film sees him rapidly processing a flood of mixed emotions.

David Mackenzie is no slouch at calling the shots behind the camera, and instills his film with a dual aesthetic informed by white trash poverty (fast food, cheap beer, unemployment, mobile homes) and tchotchke Americana (neon signage, casinos, big trucks, Wal-Mart). He uses established songs from the likes of Waylon Jennings, Gillian Welch, and Townes van Zandt alongside instrumental pieces from Nick Cave and Warren Ellis to further the atmosphere. When violence is called for, he delivers, and often does so with a refreshing dearth of cuts.

But the major creative force at work here is undoubtedly actor-cum-filmmaker Taylor Sheridan, who had recently penned Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario and would go on to direct Wind River and Those Who Wish Me Dead, as well as launch the ongoing television drama Yellowstone. His screenplay is impeccable (if you can accept the narrative setup and lack of a clear protagonist)—restrained exposition, understated social commentary (though its most prominent themes are front and center), occasional satire, memorable dialogue, economically drawn characters, a tantalizing denouement. He also subtly allows his characters to inform his drama, providing numerous little wrinkles to otherwise “routine” proceedings that cause the moments to sink in. Consider the waitress (Katy Mixon) who won’t hand over the tip the brothers left her even though it could be evidence because it is equivalent to half her mortgage payment and she’s gotta keep a roof over her babies’ heads.

Classical in texture and form and yet modern in setting and themes, Hell or High Water is lively enough to keep us on the edge of our seats but patient enough that each encounter comes with real trepidation on behalf of the characters. It finds a solid middle ground between contemplative and popcorn cinema.