“Here I was sitting with my baby son on a prison bus. I don’t think it gets much lower than that, you know?”

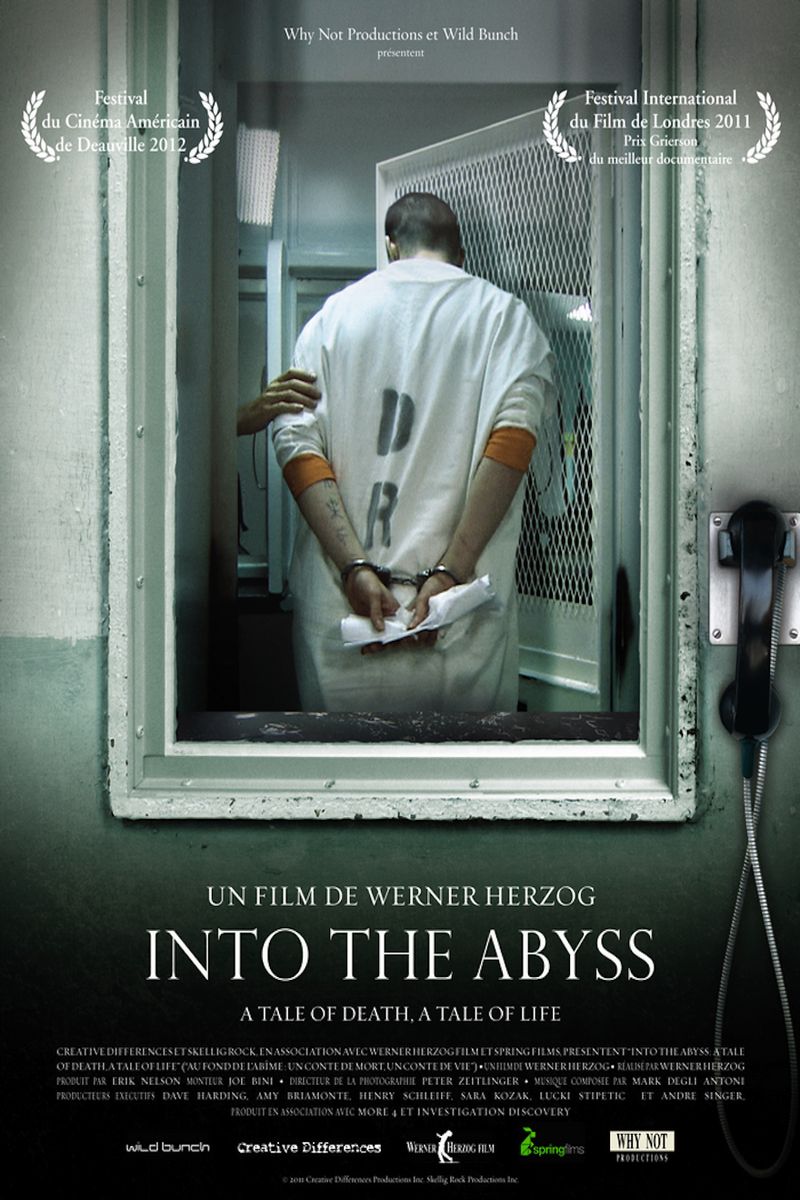

In October of 2001, two Texas teenagers set out to steal a fancy car. By the end of the night, they had murdered three people. Werner Herzog’s Into the Abyss profiles these two young men and the seismic impact of their heinous actions as one of them waits on death row and the other faces a forty-year sentence.

Born out of the same filmmaking effort that produced the miniseries On Death Row, this sobering and profoundly sad documentary does not concern itself with guilt or innocence—though, to be clear, there is never a question of guilt. When its primary subjects provide accounts that contradict each other as well as the official police account, Herzog simply moves on, favoring rumination and the search for deeper truths over clinical investigation or intricate legal matters.

The filmmaker, who also serves as primary interviewer, does not feign objectivity. He states his own opinion early in the film when he tells the young man on death row that he doesn’t need to like him in order to believe that he doesn’t deserve to be killed. He doesn’t offer cogent arguments to support his belief, but putting it on the table allows him to move past the potential hangup, to aim at different targets and explore new paths as they open to him, resulting in a trademark multifaceted essay that is equal parts anthropological investigation and thoughtful philosophical conjecture. (It’s also helpful to consider that the case here is essentially a worst case scenario for someone trying to argue against the death penalty.)

There is a remarkable amount of archival police footage (astutely edited) and crime scene recreation via eyewitness interviews and site tours, but the real takeaways here are almost entirely disconnected from the sordid details of the crime. They’re also never outright articulated, but rather fall out of observations made during the interviews. To wit, the cultural conditions that might lead to such a thoughtless crime (HUD housing, food stamps, rampant illiteracy, drugs, alcohol, trailer parks), and the near-unanimous lack of satisfaction with the capital punishment, even among the bereaved and especially among those involved in the execution process.

Where the director’s sense of humor usually comes through in his narration, here he refrains, using text to fill in pertinent details and otherwise only speaking during interviews. His strength as an interviewer is apparent from the very first conversation which features a compassionate chaplain whose face is typically the last thing death row inmates see before giving up the ghost. In the span of a few minutes the man is caught off guard by Herzog’s bluntness (“Why does God allow capital punishment?”) then finds himself tearing up as he describes braking his golf cart to avoid taking the lives of two playful squirrels in his path. Elsewhere he searches for insight by interviewing parents, siblings, spouses, prison workers, policemen, and so on, most of whom appeal to God in one way or another. Perhaps the most affecting conversation comes from the father of the young man who received a forty year sentence, who considers his own persistent failures the cause of his son’s errant path. That the son has elected to follow in his father’s footsteps by artificially having children who will have to visit him in prison until they’re adults is disheartening.

Herzog’s intention isn’t to prove a point or to editorialize, but to simply observe, to dredge up real human emotions, to explore the unfathomably tangled web of the human condition. That he often gets there through unorthodox lines of questioning ensures that the film could have been made by none other.

Without really attempting to persuade, then, Into the Abyss dives headfirst into a difficult subject and examines it with a clear head. Unsurprisingly, it discovers that mankind is fallen and that meditating upon our fallen state in its extremes (or worse yet, finding employment that regularly brings one in proximity with such extremes) is bound to leave one feeling numb and despondent.