“And where does the newborn go from here? The net is vast and infinite.”

As more aspects of our lives are lived out in virtual contexts; as more of our habits and thought patterns are digitized and fed back to us through algorithms; as tech-native social phenomena begin to emerge and inform the zeitgeist; as we become further integrated with the connected world; as psyches are calibrated like mechanical tools; as the web affords access to untold knowledge while trivializing so much of it; as artificial intelligences begin painting and writing stories; as technological tinkering delivers fewer breakthroughs and more platforms that amplify degeneracy; as automation makes impossible tasks repeatable but impoverishes large chunks of the workforce; the resonance of Mamoru Oshii’s existentialist cyberpunk anime Ghost in the Shell grows ever deeper.

Though it eventually addresses its philosophical themes in a free-spoken manner, the film begins by presenting a dense, punchy neo-noir narrative set in a futureworld of extrapolated technologies. Human flesh is augmented with cybernetics. Prosthetic organs stand-in for their natural counterparts. Entire bodies can be purchased on the black market, or patched up piecemeal like the Ship of Theseus, more or less producing a new species. Brains connect to the web. Minds communicate telepathically. False memories are implanted into unwitting recipients. Assassins disguise themselves with adaptive camouflage. In this sexless and deathless future, humanity has been reduced to a “whispering ghost.” We’ve crossed the event horizon, and the emotions that previously defined us have been rendered meaningless.

It opens on a tantalizing sequence that perfectly encapsulates its commitment to savage, tech-infused style—a political assassination that sees secret agent Motoko Kusanagi flipping through the air, nude beneath her thermo-optical shroud, to blow the noggin off of a foreign diplomat. We catch a glimpse of the victim’s severed spinal cord dangling from his headless body before Kusanagi dissolves into the night sky in slow motion to reveal a glowing cityscape beneath her, just as a synthetic tribal chant ushers in the opening credits (music for the film was provided by Kenji Kawai). This captivating opening scene, followed by the assembly of a cyborg during the opening credits, nutshells the film’s cyberpunk ethos by succinctly introducing an intricately woven mystery bursting at the seams with wild technology, cold sensuality, and elegant violence.

Memory cannot be defined, but it defines mankind.

(Though it could be accused of engaging in the same brand of fanservice that shamefully marks so many animated properties—I mean, I suppose “her invisibility suit works most effectively when she’s naked underneath it” is a sufficient rationale; and of course the physical nature of our bodies place a crucial role in the story—Ghost in the Shell is far less exploitative and far more introspective than other films of its ilk. Its nudity is never erotic and is seamlessly integrated into a brilliant aesthetic rather than the primary feature of jagged detours into embarrassing fetishization. But I digress.)

In counterpoint to the film’s brutal flourishes, in between the acrobatic shootouts and breathless clue-finding Kusanagi finds herself plagued by doubts; the rotten fruit of seeds planted by an encounter with a “ghost-hacked” garbageman, a brief glimpse of a doppelgänger, and her pursuit of the Puppet Master—a sentient being born out of the “sea of information” who craves the same human qualities that humanity has given up. Namely, sex and death. As she tracks down this mysterious entity, Kusanagi is sidetracked by her own crisis of identity, which echoes that of Deckard in Blade Runner. Who is she, really, beneath that integrated vessel of flesh and technology? What would happen if she resigned from Section 9—a process that would involve decommissioning her augmented mind and body? Actually, come to think of it, she’s never seen her own brain (the only part of her that’s organic)—how can she be sure she is human at all, or that her memories aren’t fabricated implants? “Maybe there never was a real me in the first place,” she wonders aloud. And if consciousness can abiogenerate out of the digital morass, what does it mean to be human anyway? “I think, therefore I am” is no help when you suspect your thoughts might not be your own.

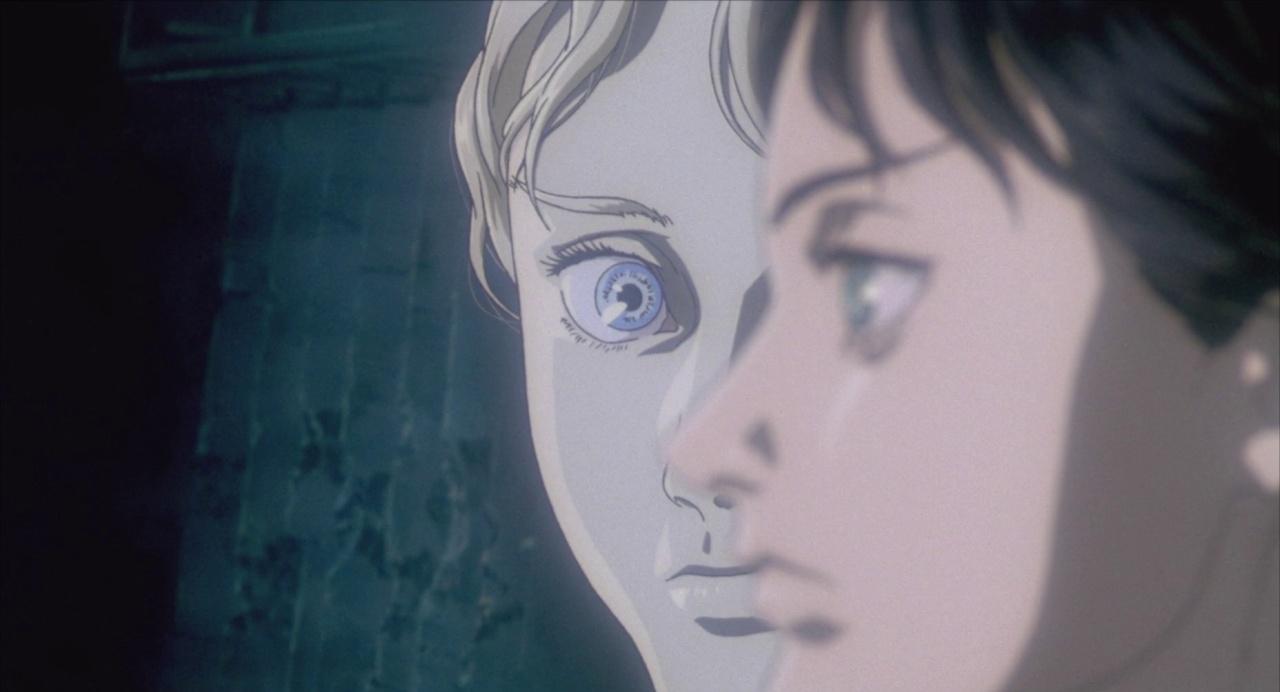

Such questions are explicitly discussed through dialogue, but also artistically rendered through visual and aural means. Mirrors, windows, and water are used to great effect to emphasize notions of duality, dissociation, and empathy during lingering interludes of audiovisual montage (floating trash, storefront mannequins, water taxis, jumbo jets, bustling streets, scaffolding, billboards, a basset hound), while subdued ambient music employed during narratively tense sequences produces a sense of the numinous.

In a film that frequently approaches the transcendent, perhaps the most sublime passage comes when a ghostly, possibly subconscious voice interrupts a difficult philosophical conversation between Kusanagi and her partner Batou by quoting from 1st Corinthians 13: “What we see now is like a dim image in a mirror. Then we shall see face to face.” This comes just after Kusanagi has surfaced from a deep dive into the ocean undertaken so that she might feel primal human emotions. Later, after she has come to fully know and be fully known by the Puppet Master—an asexual ritual that fulfills, in a grotesque, alien way, what is perhaps humanity’s greatest longing—creating a new form of transhuman life, she returns to the Apostle Paul’s words.

Over and above the questions its characters bat around, Ghost in the Shell considers the mechanism by which such quandaries might arise—how an individual mind interacting with its environment is stirred to contemplation. It suggests that our sense of alienation, of not quite fitting in, is the very thing that distinguishes us from others and enables us to affect change in the world. Every bit of information a person accumulates across a lifetime may only be a drop in in the bucket, as Batou puts it, but it is exactly that limited perspective that makes us distinct individuals.

Even a simulated experience or a dream is simultaneous reality and fantasy.

All of this thoughtful cogitation is intoxicating to ponder in its own right, but it’s absolutely enlivening to encounter it laced into a masterfully realized cyberpunk setting and explored through a taut neo-noir storyline. Breathtaking and awful (in the archaic sense of the word, meaning it inspires both fear and awe), Ghost in the Shell set a high bar for adult-oriented animation by confronting the oncoming hyper-connected world with curiosity and enthusiasm, but also trepidation. Notions of free will, consciousness, the soul—these are hazily defined for actual people, but now we must consider what they mean for virtual beings. Living in a global culture that has inched ever closer to the science fiction depicted in the film, I recall the words of Special Agent Dale Cooper. “I have no idea where this will lead us, but I have a definite feeling it will be a place both wonderful and strange.”

(Of course, one cannot review Ghost in the Shell without mentioning its clear inspiration on The Matrix. And so yes, it’s quite obvious, from the green “digital rain” of its credits to the templeless sunglasses to “jacking in” to exploding watermelons to the framing of any number of action sequences. Despite these aesthetic and genre similarities, they’re vastly different films—the earlier film an arthouse-inspired meditation on the future of human society disguised as a sci-fi noir, the later one a sincere actioner about disconnecting from the system. Their strongest connection comes from their suggestion that harnessing technology, rather than allowing it to restrict and repress, is both a formidable goal and an outcome undesirable to the powers that be.)

Sources:

Baker, Dan. “Ghost in the Shell (1995)”. Cinema Faith. 5 April 2017.

Wang, Benjamin. “Ghost in the Shell (1995): I Believe In Miracles”. Film Inquiry. 27 February 2017.

Sipos, Meg, & Botts, Eric. “The End of Sex, Death, & Humanity”. The Other Folk. 29 April 2022.