“A good cop can’t sleep because he’s missing a piece of the puzzle. And a bad cop can’t sleep because his conscience won’t let him.”

Take a quick glance over Christopher Nolan’s oeuvre and you could easily miss the unassuming Insomnia, a mostly straightforward cop thriller nestled in a filmography otherwise full of narrative complexity and tricky set pieces. Unlike his other works, Insomnia never tries to hoodwink the audience, instead allowing the unfolding mystery to engage the viewer. With its themes of self-deception and obsession, it fits well within Nolan’s body of work, but it lacks some of his flashier hallmarks.

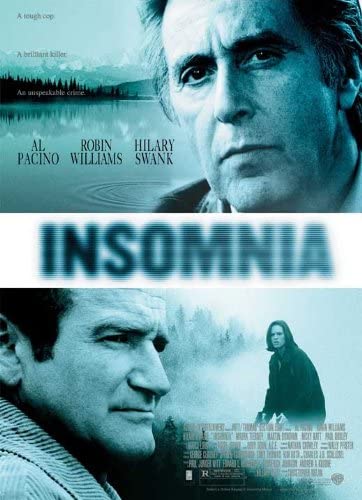

Nolan’s movie is a remake of a Norwegian film, also titled Insomnia, and directed by Erik Skjoldbjærg. It stars Al Pacino in one of his best late career roles as Detective Will Dormer.1 Will and his partner Hap Eckhart (Martin Donovan) are brought from L.A. to the listless town of Nightmute, Alaska to help with the case of a murdered girl, Kay Connell. Simultaneously, Dormer and Hap are at loggerheads about an Internal Affairs investigation into one of their past cases. Dormer had planted evidence to get a conviction and Hap has decided to cut a deal in order to save his own skin. Fundamentally, Dormer knows he was in the wrong to do what he did—believing the ends justified the means—but he also knows that allowing Hap to aid the investigation would call into question all of his previous cases—his entire life’s work. What good is being honest about it now, if the rapists and the murderers he has put away over the years may all go free?

When they arrive in Nightmute, the detectives are greeted by Ellie Burr (Hilary Swank), a local detective who is a model of innocence and integrity. She has studied all of Dormer’s cases and idolizes him. Dormer quickly reviews the case and the body. The killer had taken the time to clip Kay’s nails and wash her hair. He quickly rules out the boyfriend, suspecting her mysterious out of town acquaintance instead.

Almost too quickly the detectives—joined by the local police force—are chasing a suspect through the foggy Alaskan night (but it’s Alaska, so there is plenty of light). They had set a trap at a lake house, but spooked the suspect accidentally. A shot is fired and one of the local boys goes down, but Dormer continues giving chase. In the ensuing chaos Dormer sights the suspect, and opts to fire; but when he approaches the body, he realizes that he has shot and killed Hap.

Dormer acts quickly, and is able to cover his tracks, fooling his colleagues into thinking that the suspect had tagged his partner. But he is racked by guilt. He no longer has to worry about Hap jeopardizing his legacy and letting criminals back onto the streets, but his conscience eats away at him. The Alaskan sun never sets, and he lies in bed, light blaring through the curtain, chewing gum, drinking by himself, and staring at the obnoxious alarm clock. Hap’s face flashes into his mind. Did he know it was Hap before he fired the shot? Did he mean to kill his partner? On the surface we’re watching a cop thriller (with a hint of noir), but at its core Insomnia is a morality tale.

In the confusion on the fateful day, the suspect had dropped his gun in shock. Shrewdly, Dormer had picked it up and kept it himself. Discreetly (as discreetly as one can shoot a gun in the middle of the night), he pumps another round into a dead dog, and then digs it out. When he takes the rounds to the lab for analysis, he switches the round that killed Hap with the one from the dog. Now, no one has any knowledge of his role in Hap’s death—no one except Walter Finch (Robin Williams), the man that they had lured to the cabin that night.

Several years prior to the release of Insomnia, David Fincher’s Se7en kept Kevin’s Spacey’s role as the villain a carefully guarded secret. Spacey had just received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for The Usual Suspects and the team thought it would be a giveaway to have him on the opening credits and in advertisements for the film. While Williams’ role wasn’t concealed to quite that degree, it is certainly a surprise to see Robin Williams play the villain. It was a gutsy move, casting him way against type, but he absolutely nails it. In the years preceding Insomnia, Williams’ roles were generally family friendly—things like Jumanji and Flubber. He also had some more dramatic roles, like Good Will Hunting and What Dreams May Come, but those were still mostly just Williams playing versions of himself—goofy, upbeat and affable. Here though, he is really inhabiting a role that is completely outside of his usual realm. In hindsight, 2002 ended up being a really uncharacteristic year for Williams, with his other two roles being likewise off the beaten path. He played “Rainbow” Randolph Smiley in Death to Smoochy, a dark comedy about a disgraced children’s TV show host, and Seymour “Sy” Parrish in One Hour Photo, about a solitary, socially inept photo technician.

The casting of Williams is brilliant because we find it hard to dislike him—because he’s Robin Williams. He’s Mork, Peter Pan, the Genie. He wouldn’t kill anybody. So when he tries to convince Dormer that he didn’t intend to kill Kay, we start to believe he may be one of those misunderstood characters, creepy but gentle, who let his emotions get the better of him. And we begin to suspect that Dormer maybe doesn’t possess the instincts that his reputation would indicate. But when Finch describes the murder to Dormer over the phone, it becomes clear that Finch is a monster. He just doesn’t realize that he is one.

As Dormer’s mental well-being continues to deteriorate and he racks up a half dozen sleepless nights, Ellie begins to piece together what has happened. When Finch and Dormer mortally wound one another, and Ellie bends over her dying idol, she tries to throw away the evidence of his crime. He catches her hand, and implores her to remain honest. Dormer drifts off into sleep at last, having accepted his moral failings.

The film is not as brilliant as Nolan’s most lauded efforts. It doesn’t feature technical wizardry or mind-blowing non-linear plot elements. There’s no space travel, no superheroes. But there is a tight, compelling cop story with a strong emotional undercurrent. There is a cast led by three Academy Award winners. And there’s a simultaneously gorgeous and eerie setting with unique elements that are crucial to the story. A solid stepping stone for Nolan before he would move on to direct the Dark Knight Trilogy, and a string of other blockbusters.2

1. After the release of Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, the “last great Pacino performance” may be open for debate.

2. It would be nice if it was still the norm today that directors moved from smaller to larger projects gradually. Nolan had already directed Following and Memento, but still had to prove himself with Insomnia before a studio would give him a large project like Batman Begins. In recent years, directors have been pulled onto major projects with only a single promising film to their name, and the resulting films suffer due to the filmmakers’ underdeveloped skill sets.