“This island is a playground to some… but a graveyard to others.”

During my last semester of college I decided to buckle down and go for a straight A semester that would bring my overall GPA up to a specific number I wanted to hit (mission accomplished, by the way). The catch was that I had also saved a handful of intensive engineering courses until last, meaning my free time was limited, and when I finally staggered my way to those infrequent evenings of downtime, I was utterly exhausted and my brain more or less on the fritz. The pastime I stumbled upon and which sustained me through those grueling months was Just Cause 2, an action-above-all-else sandbox shooter that plays it entirely straight with the player.

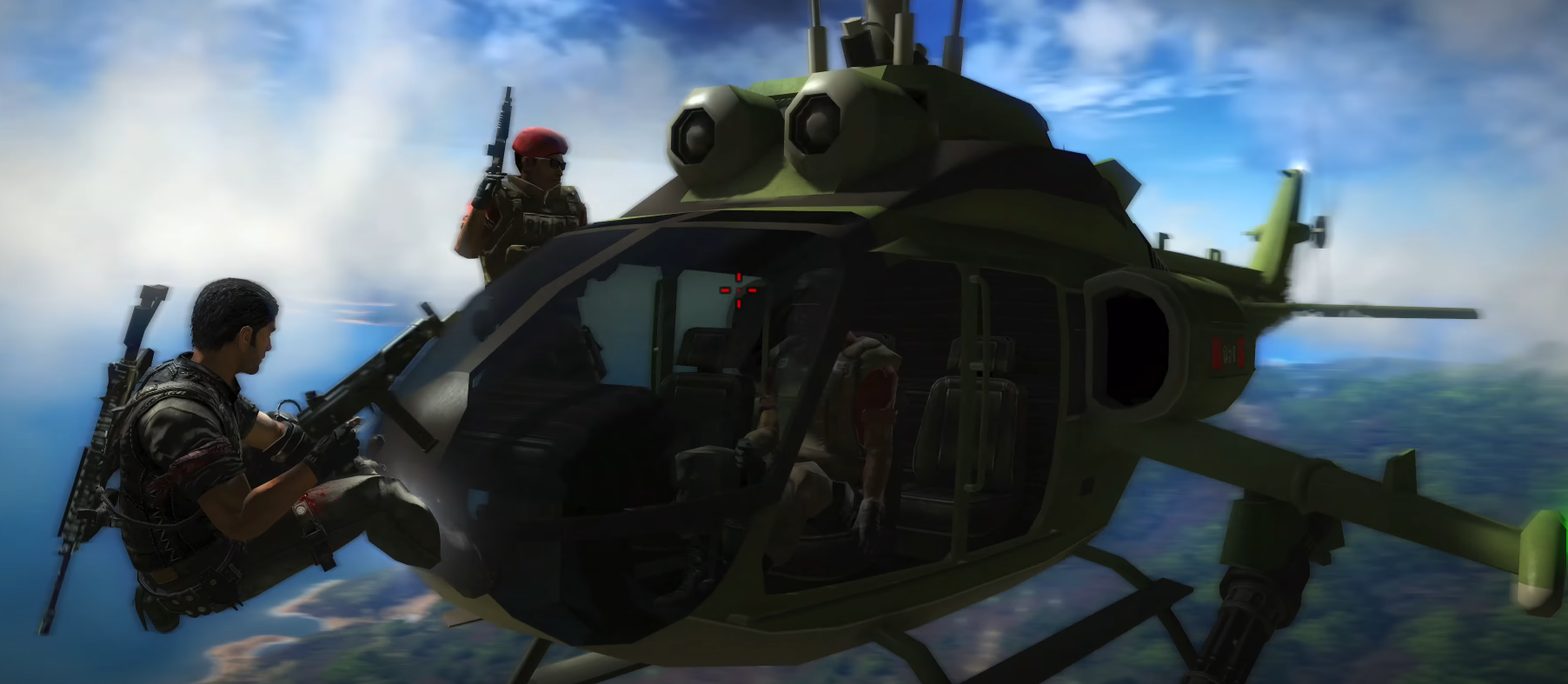

This is a game that tosses you onto a military occupied island, equips you with guns, a grappling hook, and a retractable parachute, and gives you the slimmest excuse to rip the environment to shreds. A game that lets you hijack a helicopter and then eject and grapple onto anther one, or leap between cars as they speed along a jungle road.

There’s a story so shallow you’d let a baby try to swim in it unsupervised, that provides enough of a framework to orient the player as they once again take control of gun-for-hire Rico Rodriguez. But the real reason to play it is that it’s a pure pleasure to traverse the environment with the grapple-parachute movement system which is both fast-paced and vertically-oriented. It takes a while to feel natural, but eventually you’ll be basically be able to fly by tugging yourself along with a parachute deployed. Or you can also fly in myriad planes and helicopters, and the land and water vehicles are a heck of a lot of fun too. From an adrenalized gameplay perspective, it blows Just Cause and most other similar games right out of the water, routinely delivering unscripted moments of surreal action. One only wishes it had integrated some of the grapple combat moves from Bionic Commando.

What drew me to the game while I was under extreme stress was its gigantic map, full of ramshackle villages and military outposts that needed to be discovered, ransacked, and, in the case of the latter, demolished. That the game understands this open-ended pursuit is its main appeal is to the developer’s credit, even if a few game design elements tend to inhibit its most compelling modes of play. It does turn the entire thing into something like a collectathon, but the collectibles are low-stakes skirmishes that the game tracks for you instead of a tedious grind. (I mean, there are literally thousands of other conventional collectables, but I digress.)

Anyway, I found discovering and clearing the locations to be an extremely relaxing exercise that was perfect for short spurts or hours of zoned out bliss. I revisited the game recently when I was undergoing an extremely stressful time at work (that prompted me to search for a new job, which meant the stress was compounded by the stress of interviewing), thinking that it may serve a similar function for me. I enjoyed my time with the game immensely, but, just like last time when I dropped it upon graduation, once the stressful situation was resolved (new job—less politics, less gaslighting, less chest pain, higher salary) I didn’t feel inclined to keep plugging away at it, and I doubt if I’ll ever feel compelled to finally conquer every single cut-and-paste location. But is that really a knock against a game that I’ve already put dozens of hours into?