“Can we watch something happy now?”

When I was about ten or eleven, I had a strange, nightmarish experience during a sleepover at a friend’s house. It wasn’t the kind of nightmare where something truly awful happens—nothing you’d call traumatic—but it was weird, inexplicable, and haunting. Even now, I sometimes have dreams that repeat all night long. I’ll wake up feeling like I barely slept, stuck in a loop of missing the game-winning shot, or something equally frustrating. Usually, the dreams are more abstract. That night, I was on some kind of watercraft, drifting on the ocean, with something dark and sinister rising from the depths, then retreating, then approaching again—an evil torpedo.

I also hardly ever wake up and stay awake in the middle of the night, but this dream left me so flustered that I sat up in bed, preternaturally alarmed. I was on the bottom bunk, my friend on the top, and I was sitting there in the darkness, unsure what to do, when a dark figure entered the room—my friend’s dad. He didn’t say a word, seemingly frozen in surprise at finding me awake. I couldn’t see his eyes in the darkness—he likely couldn’t see mine either—but we just sat there, silently staring each other down at 3 a.m. And then he left. What was he doing? Checking to make sure we’d gone to bed? Creeping? Combined with the lurching dread of the nightmare, it was a terrifying moment. Why didn’t he just say, “Can’t sleep?” or “Do you need a snack?” Why did he just lurk there in the doorway and then leave?

I’ve always wanted to adapt that memory into a short story, and maybe I still will someday, but the rendition above was typed out on my phone while eating breakfast with my daughter crawling all over me and Batman Beyond playing in the background. It probably lacks all the menace that charged the moment.

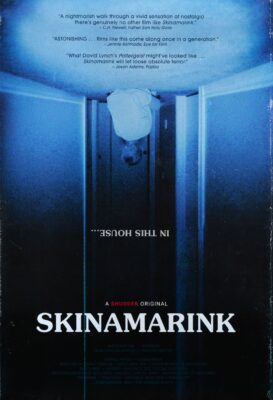

I felt compelled to write this memory down because it kept resurfacing as I watched Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink, a micro-budget horror film about two children who awaken to find their parents missing—and the windows and doors of their home inexplicably gone. With long, static shots of dimly lit hallways, shadowy corners, and close-ups of scattered Legos, stuffed animals, power outlets, and crayons, all dimly lit by nightlights and a CRT television playing public domain cartoons, the film slowly uncovers a small pocket of reality where the natural order has been disrupted.

The kids’ father reappears—or maybe it’s a malicious entity that looks and sounds like him—sitting silently on the bed. Their mother, who shouldn’t be corporeally present, makes a fleeting appearance. A disembodied voice haunts the deceptively oppressive, static-hiss soundscape, beckoning the children to come upstairs or look under the bed, sometimes encouraging violence. Occasionally, it’s obeyed. Sometimes subtitles suggest words that aren’t audible to the audience. A doll levitates and clings to the ceiling. The few noteworthy events tend to happen offscreen, or maybe only in the imagination. The four actors (Lucas Paul, Dali Rose Tetreault, Ross Paul, Jaime Hill) never show their faces, and even the rest of their bodies rarely appear in the frame. The camera constantly tilts away from what we want to see, echoing the approach of other low-budget horror successes like The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity (or that oscillating fan trick in Paranormal Activity 3), implying more than it shows. The digital grain and visual distortion swirl like jet-black worms, while the still frames compel us to scan the vast, inky blackness for things that aren’t there. It’s hard to capture in words just how visually indecipherable the film is—lit with intentionally inadequate sources, from angles chosen to confound.

Stylistically, Skinamarink is aggressively unconventional, more in line with the experimental approaches of Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, and Chantal Akerman than with modern horror directors. Though Ball does cite Black Christmas as an influence, his work feels closer to avant-garde cinema. It’s also impossible to make a film in the realm of surreal dreamscape horror and ambiguous esoterica without drawing comparisons to David Lynch—especially his first and last feature films, Eraserhead and Inland Empire—but I think that comparison is a bit strained.

Ball began his career adapting YouTube comments about childhood nightmares into short horror films. Skinamarink exploded because snippets were passed around on social media platforms. But can this unique brand of purely atmospheric horror sustain a feature-length film? Not all of the chances it takes bear fruit, and fans of mainstream horror will likely be put off by its crackling sound design and inscrutable visuals. But I found its use of old Fleisher cartoons, its lo-fi aesthetic, its atmospheric non-story, its child’s-eye perspective, and its well-timed jump scares to sporadically evoke childhood frights. It creates a state of nervy, disorienting anxiety similar to Lake Mungo or The Wolf House.

I took an experimental film class in college and went through a period of wondering how anyone could “enjoy” Wavelength, Dog Star Man, or Empire, and came out the other side with an appreciation for various outré schools of thought.1 Without that background, I’m sure Skinamarink would have been a totally bewildering and aggravating experience—which is exactly how it’s been received by much of its audience, caught in the same creepypasta zeitgeist that fueled We’re All Going to the World’s Fair and marketed as a conventional horror-thriller. Still, it made $2M against a $15k budget, an unqualified success for a homemade, avant-garde, non-narrative horror film that uses none of the cinematic language the general public has been conditioned to expect.

“Enjoy” might not be the right word for my experience with Skinamarink, but I’m glad I made the effort. At times, it feels like a slog and it takes itself too seriously. With about fifteen minutes trimmed, it could more effectively achieve its aims. But if the viewer is in the right frame of mind, it works its way under the skin, making you feel existentially vulnerable and exposed, where a regular old scary movie delivers scares that last only a moment. That it only delivers those unique chills sporadically—and is otherwise an inert test of patience—makes it hard to recommend to anyone who doesn’t want to philosophize their film-watching experience.

1. A couple of my gateway films included Kenneth Anger’s Puce Moment, Jonas Mekas’s Notes On The Circus, Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, Chris Marker’s La Jetée, and David Lynch’s The Grandmother. Considering their very purpose is to experiment, and a failed experiment is not necessarily an unfruitful one, the vast landscape of “experimental film” is extremely hit-or-miss.