“I need sex and money.”

Like many award-winning films about deviant sexuality in the past handful of years, Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things benefits from wearing the emperor’s new clothes. I understand that the tendency in mainstream thought right now is to blindly approve any sort of outré kink. The weirder the better. And that every time that happens, existing taboos soften and the lines-that-shall-not-be-crossed become a little less certain. Film studios have picked up on this, intuiting that critics will stick their thumbs up in unison and moviegoers will go with the flow if they just blast degeneracy down everyone’s throats. There have been films that use sexual deviancy as a primary theme and proved piercing and insightful. Poor Things, about an infant whose brain is transplanted into the body of her dead socialite mother, is not one of those films, even though it holds itself out as such and has been treated that way by critics and the powers that be.

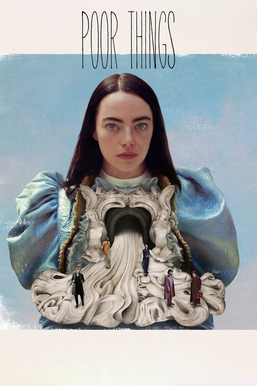

It has a neat hook, with a scarfaced and compassionate mad surgeon-scientist Willem Dafoe presiding over an arcane laboratory reminiscent of James Whale’s Frankenstein, splicing dogs and chickens, tinkering with corpses, himself a victim of scientific hubris, who belches bubbles of gastric juice and believed that “God’s monster” was a commendable experiment to devise. And as Emma Stone’s Bella “comes of age” and explores a fantastical Victorian London along with her sexuality, unaware of anyone’s expectations of her and dispossessed of self-consciousness, the film is not without food for thought and a few laughs. I even laughed out loud when she voiced her intention to punch a baby crying its lungs out at a restaurant, because, of course, she has the mentality of a toddler. But because she lives in the body of a good-looking woman, her sexuality is quickly developed and exploited in increasingly disgusting ways: by her creator’s assistant (Ramy Youssef), by a lascivious lawyer (Mark Ruffalo), by a procession of slimy men who pay for her body, and by a fellow prostitute (Suzy Bemba) who instills poisonous ideas in her sponge-like mind. Once she learns how to masturbate, she becomes a good little hedonist. Sex for fun, sex for money, sex with strangers, sex alone, sex with kids, sex with an audience. The lawyer thinks he’s a boundary-crossing libertine, but then he takes Bella out in public where all she wants to talk about is sex. Her entire existence is reduced to pure sensation, externalized in her extreme expressions, which would strip the character of any sense of interior life (which children do have) and reduce her identity to her reproductive glands if she didn’t also inexplicably show a passing interest in politics and charity.

This scenario could have been developed in meaningful ways (synopses of Alasdair Gray’s parody novel suggest it’s maybe not quite so terrible, and I can envision a gender-swapped take on Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser), into a dreadful fantasy, a comedy, or a satire—and there are certainly elements of all three (Ruffalo is particularly funny as a debonair sleazeball even if his performance is one-dimensional)—but Lanthimos undercuts the entire enterprise by endlessly circling the drain of smutty sexual depravity. I mean, kudos to Emma Stone for being brave or whatever, and I didn’t actually time it, but she’s gotta be naked for like fifteen or twenty minutes throughout the film, which is an unfathomably long time for anyone to be naked in a movie, let alone a big name star like her. I’ve seen a few critics wonder about the odd uses of fisheye lenses and those shots where it looks like we’re peeking through a keyhole for no discernible reason and the switches between black-and-white and color and those surreal tableaux that serve as backgrounds for the chapter headings. But if the goal of film analysis is to tease out why certain filmmaking decisions were made and what purposes they serve, I’m much less interested in the jagged film style Lanthimos employs than in the fact that he chose to make like 10% of a promising dark fantasy about female self-empowerment into degrading softcore porn. I don’t know the answer, but all the obvious artsy-fartsy subtext and the surreal set designs and Stone’s uncanny and overblown performance and even the weird atonal score (Jerskin Fendrix) are more or less a reprieve from the relentless pornography, which is the centerpiece.

Taking into account the rest of the director’s oeuvre, it is safe to say he likes to push buttons and conduct large-scale experiments built on high concepts. In that light, Poor Things is definitely in his wheelhouse; we just need to tease out the nature of his experiment. My guess is it’s an experiment on the critics and the audience rather than an expression of artistic intent: let’s just bombard the reprobates with quasi-pedophiliac pornography and see if they’ll call it high art. The results of this multiple Academy Award winning experiment about “sexual liberation” speak for themselves. Yikes. Imagine if they’d actually had the courage of their convictions and didn’t cast an attractive woman in the role of the sex addict, and chose instead someone like Steve Buscemi? That would have knocked the wind out of the pseudo-feminist sails, methinks.

Then again, if I take a step down from my soapbox and imagine this film with its most repellent bits excised, with a spirit that’s a little less caustic, without a bunch of perverted intellectuals drooling all over it and celebrating moral decay, I can envision a horror comedy that stitches together the best parts of Edward Scissorhands, The City of Lost Children, The Lair of the White Worm, and Frankenhooker. If this didn’t have the reputation as something that is supposed to be really meaningful and insightful, if it could just be a dark comedy set in a steampunk fairytale universe, my reaction to it might have been totally different. Then again, again, maybe my tastes have ossified so completely at the ripe old age of thirty that the faux-arthouse chic, brazenly charmless characters, and grotesque ethics will continue to strike an unreceptive palette. Then again-again-again, maybe my gut reaction is right and the smirky hipster bluster is just bad art and not nearly as clever, subversive, or sophisticated as everyone hyped themselves up to believe it is.