“It’s not a low art, I want you to know that.”

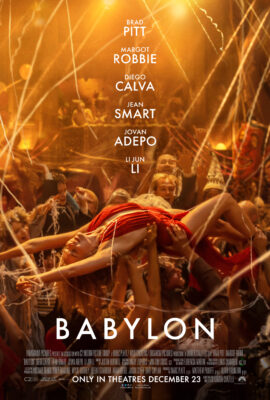

Babylon isn’t a strikeout, but it’s a pretty big swing to not be a home run. And the swing is the most memorable thing about it. An incessantly showy period piece set during Hollywood’s transition to the sound era, it continues Damien Chazelle’s critical-eyed infatuation with Tinseltown that began with 2016’s La La Land. Once again, Singin’ in the Rain is an obvious inspiration, from the setting to the costumes to the diegetic music to, well, the fact that clips of it are played in the film’s epilogue along with a nifty but ill-fitting montage of snippets from movie history, all the way up to present day.

But also Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon and Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. It celebrates the moviemaking mecca warts and all—its maverick pioneers, its decadent, debauched culture, its ability to speak to the sins of its time. Combining scenes of revelrous parties, behind-the-scenes anecdotes, casting couch shenanigans, and high-minded exposure of exploitative practices, it doesn’t so much tell a focused story as unfold a series of colorful vignettes stitched together by spectacular production design (Florencia Martin), bombastic camerawork (Linus Sandgren) and choreography (Mandy Moore), ironic editing (Tom Cross), and another fantastic Justin Hurwitz score.

It really leans into the hedonism—bacchanal bashes with cocaine and elephants and prostitutes peeing on perverted men, drunken rattlesnake fights, dungeons with grotesques chained to the walls and crawling with alligators, movie set deaths brushed off and forgotten, blamsphemes and f-bombs and boobies flying left and right. The prurience is distracting if not outright off putting, suggesting that Hollywood attracts broken people who bring out both the best and the worst in one another. It would be tragic if we didn’t get the movies out of it, and maybe it still is.

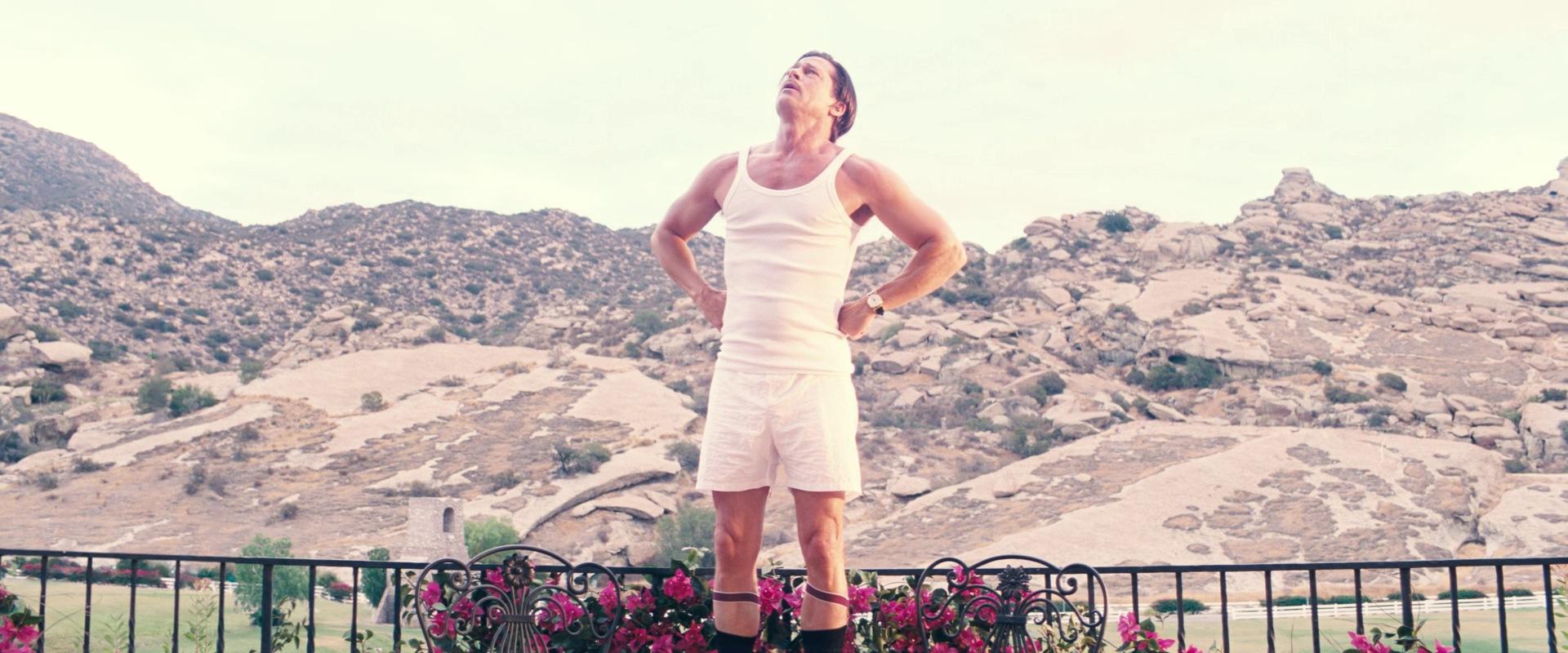

The characters include a rabble-rousing up-and-coming starlet (Margot Robbie), a seasoned veteran of the silent era (Brad Pitt), an enterprising Mexican immigrant who becomes a studio executive (Diego Calva), a gay cabaret singer (Li Jun Li), a black trumpet player (Jovan Adepo), a gossip columnist (Jean Smart), a drug dealer (Rory Scovel), a film director (Olivia Hamilton), an assistant director (P.J. Byrne), a gangster (Tobey Maguire), an agent (Eric Roberts)—all of them adequately defined by their actors to carry the wild episodes but underwritten for the emotional weight of the overarching tragedy Chazelle tries to develop. It’s just a little difficult to get all weepy over the heartbreaking beauty of cinema past when the industry’s seedy underbelly has just been exaggerated and celebrated for its depravity. Even the bleeding liberal heart side stories about the black man and the gay singer struggle to feel sincere under the avalanche of licentiousness.

I did appreciate the way that Chazelle and his team presented the early silent era scenes with kineticism and flamboyance, with the later sound era scenes made baggier and less focused by comparison, suggesting there was something in the air that dissipated during the advent of recorded dialogue—but I think that stylistic shift tends to get lost in the shuffle. A great example of what I’m talking about actually comes at the crossroads, when the studio films its first scene with dialogue and it ends with the sound guy dying of heatstroke and the assistant director threatening to defecate in someone’s mouth.

If it doesn’t connect as a raucous comedy, an epic tragedy, a Hollywood tell-all, or a paean to the magic of movies, it’s nevertheless the work of a bold, big-ideas filmmaker who is hopefully at work on another passion project, and that beats filmmaking-by-committee more days of the week than not.