“I don’t consider myself to be a particularly ethical person, but I am fair.”

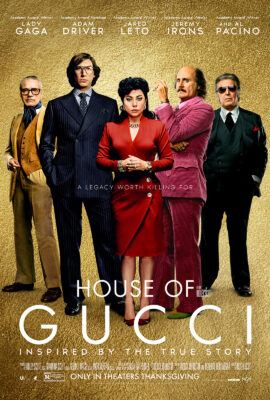

Stefani Germanotta (AKA Lady Gaga) is the only actor in Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci that finds the correct register for the material, quite appropriate for a celebrity who once wore a suit made of raw meat and convinced the media it was high art. Assuming the role of Patrizia Reggiani, who married into the luxe fashion family in the 1970s and became a mover and a shaker within the business empire, she delivers an entertaining, spirited performance that strikes a perfect balance between high camp and fact-based melodrama. (Her accent wanders all across Europe, which may tip the scales for some viewers, but I personally don’t get very hung up on that sort of thing.) We want to believe she marries Maurizio Gucci (Adam Driver) for love—especially when he’s written out of mogul Rodolfo Gucci’s (Jeremy Irons) will for deigning to marry a middle class gal like herself—but she wants it all, “Father, son, and house of Gucci,” proving wily, ambitious, and manipulative, conniving her way into the family by sheer force of will and charisma, slowly reshaping her husband’s desires until the couple is not only back in the fold, but grasping the company’s reins away from Uncle Aldo (Al Pacino), whose own “idiot” son Paolo (Jared Leto) has proven incapable of taking up the mantle. Germanotta morphs from a sweetheart into a wicked dynamo as her husband gradually starts to reject her business advice as well as her love, ultimately culminating in the spurned wife conspiring with a new age witch (Salma Hayek) to gun him down in cold blood.

That she does this while retaining an essential humanity crudely highlights the one-dimensionality of all the other performances—Pacino and Leto are particularly silly, with their mannerisms and thick accents recalling a famous plumber, while Driver has the opposite problem as the mild-mannered scion. Driver is taking himself as seriously as Germanotta, but her part has all the pizazz, and so he’s basically a lead balloon with a smiley face painted on it until he gets to be vaguely villainous in the third act by sending his wife and kids away and cheating on his wife with an old friend (Camille Cottin). Scott, for his part, exhibits an understanding that his hyper-cultivated subjects and their rampant amorality can be glamorous and funny and depressing and entertaining all at once, delivering a lavish, sanitized production and elliptically cutting through as much of the conventional plotting as he can get away with. Alas, it only comes together when Germanotta is the focal point—otherwise it’s a bit dreary, prim, and conceptually muddled—and I don’t know that the nearly three-hour film could have sustained her crazed magnetism for the duration.

If I had to choose, throw out all the respectable, polished decorum and stately legal talk and go all in on Leto’s mamma-mia antics. The other actors are most alive when they’re acting against him, so why not let the film go where it may? It was never going to be a bona fide masterpiece, but it could have been a camp masterpiece. “Never confuse shit with cioccolato,” Paolo says. “They may look the same, but the taste—very different. Trust me, I know.”