“I will not accept a life I do not deserve.”

I’m admittedly late to the Ti West game. And having only seen the Western In a Valley of Violence (2016), I’m familiar with his 2005-2013 run of horror films by reputation only. That reputation suggests that he’s at least partially responsible for the “elevated horror” trend of the last fifteen years, a subgenre of decidedly hit-or-miss quality that comes off as pretentious even when it’s good. With X, the writer-director’s return to the genre after a nine year gap (his last horror feature was 2013’s The Sacrament), he seems to be undermining that consternated sophistication of that recent crop of arthouse horror by delivering a terrific slasher flick; a charming throwback smartly tweaked with metamodern sensibilities.

It’s 1979, a group of young free-spirited types hop in a van and head out to a Southern hillbilly podunk where they plan to rent the guesthouse at a farm owned by some creepy yokels. This sounds like the premise of about six thousand horror films that came in the wake of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)—I’m partial to Tobe Hooper’s immediate follow-up, Eaten Alive (1976) and Kevin Connor’s Motel Hell (1980). It’s just as much a love letter to slasher films derived from the Hooper classic as the Hooper classic itself.

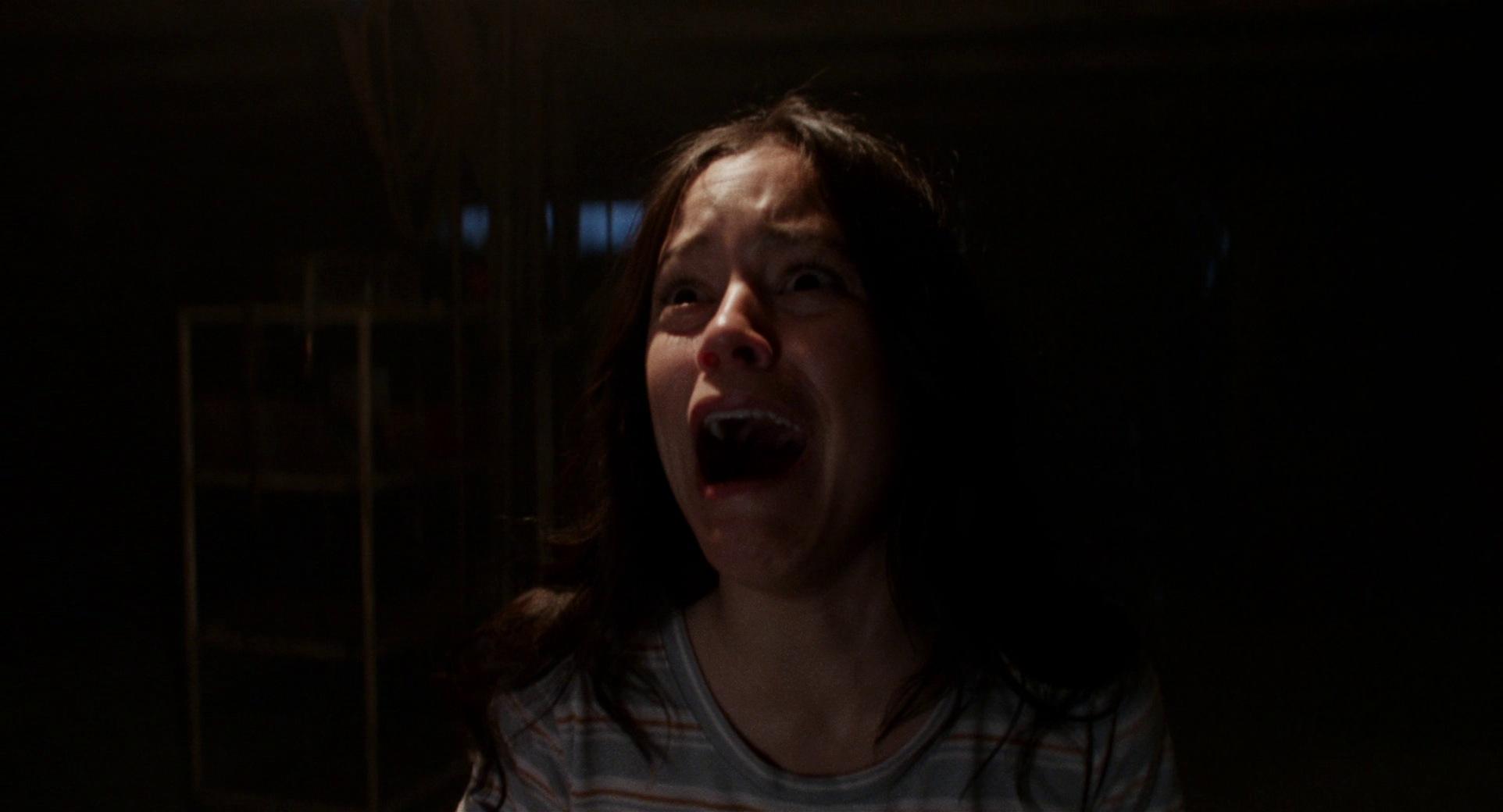

One of the wrinkles of West’s film is that the victims here (played by Jenna Ortega, Brittany Snow, Scott Mescudi, Martin Henderson, Owen Campbell) are not just stupid stoner college kids poking their noses where they don’t belong; they’re a group of bohemian pornographers who’ve taken up residence at the dilapidated farm with the intention of shooting a naughty film there amongst the cows and feed troughs and hay bales. Another one is that their leader—or at least their most promising starlet, Mia Goth’s Maxine—is sort of an anti-final girl. Confident in her sexuality, aiming to inspire lust, she commits all of the sins that her forebears paid for with their lives. Goth’s on the poster, so we sort of know, but if you went in blind, you just might suspect that Ortega’s prudish boom mic operator is the one, or that she might escape along with Maxine. Nope. Our girl is the runaway preacher’s daughter turned burlesque dancer who snorts cocaine in the opening and closing frames of the film.

Hypercineliterate, West’s knowledge of horror film history bleeds through to his characters, who not only argue about scary movies but, in making their own film, suggest they are going to make a “good dirty movie.” Is this what West himself is setting out to do with X? It’s plenty dirty and it’s plenty good.

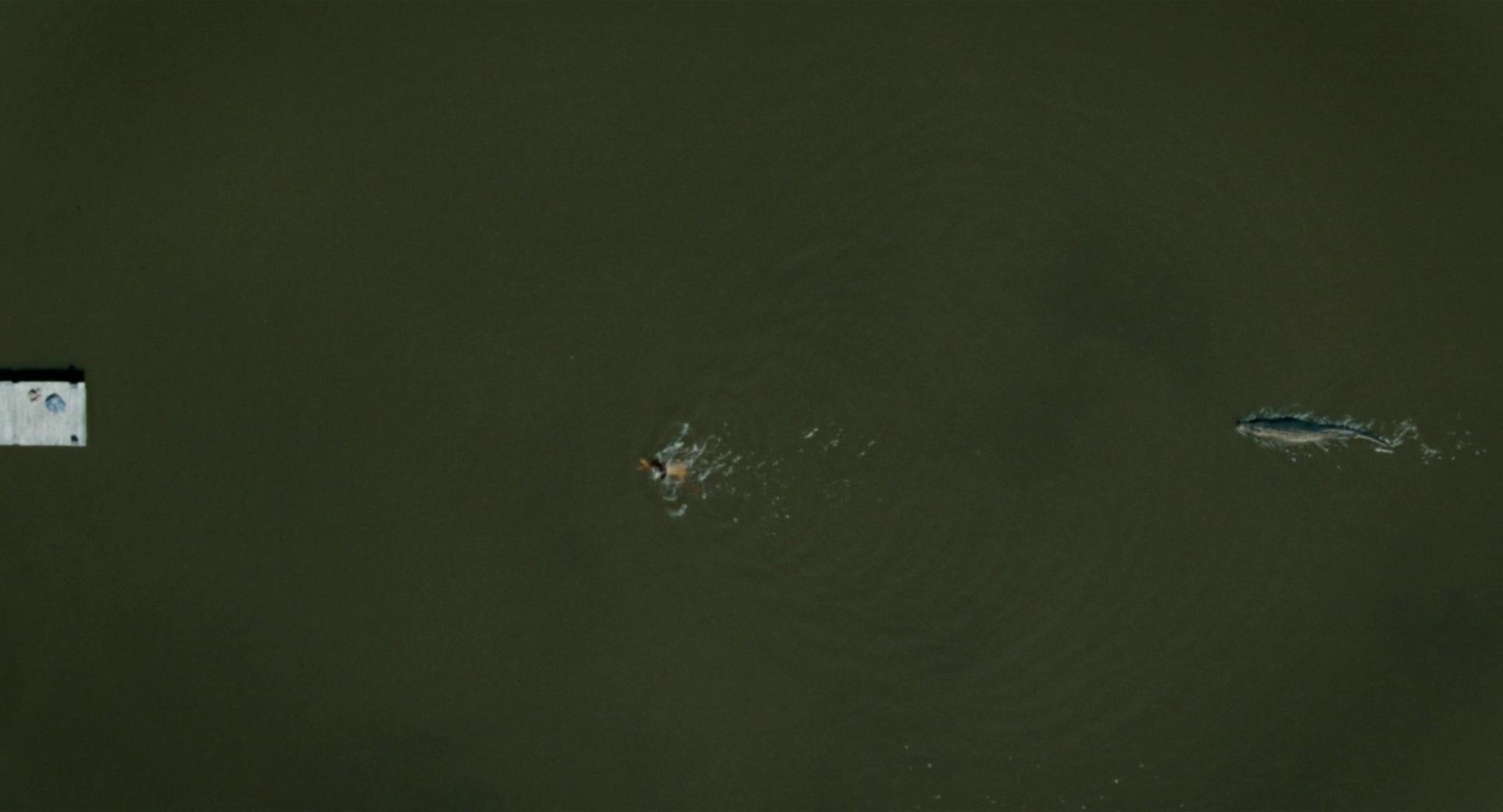

Such self-aware inversions are not altogether novel; West’s achievement is how deftly he goes about satisfying almost every broadly defined convention of the genre even as he subtly pulls off these schematic experiments. We’ve got Chekov’s alligator, pitchforks gouging at eyes, cellar doors with multiple deadbolts, topless babes, deadpan slapstick horror. We’ve got Mungo Jerry, Blue Öyster Cult, and Loretta Lynn on the soundtrack. Snow and Mescudi (who rose to prominence rapping under the name Kid Cudi) give a nice rendition of Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Landslide’ while the group hangs out in the guesthouse and has an unexpectedly thoughtful conversation about life and repression and the cultivation of desire before all hell breaks loose. There are even a few style tricks that made me smile, such as the way the film appears to open in faux-Academy ratio on a corpse-strewn farmhouse then glides through the barn doors to widen the screen, the suspenseful overhead shot of the pond and unnerving score during a skinny dipping session, or the few times it previews the upcoming action by splicing in a few frames before the standard hard cut. As our rogue film director (Campbell) tells us, part of making a good dirty movie is giving it a few touches of the avant-garde.

West might lose some of the audience with his frail villains though; decrepit, impotent old Howard (Stephen Ure) and his sexually aggressive wife Pearl (Goth in heavy makeup). Frustrated that he’s no longer capable of pleasing his woman, the old man agrees to this perverse game of luring young lovelies to his homestead then defiling and dispatching them depending on their fancy; slaying the promiscuous kids not for their free love frolicking but out of jealousy—youth is wasted on the young!

Horror films have been attacked from every angle over the years. Jason Voorhese and Michael Myers used to kill young lovers by the truckload for their misdeeds, and some called that a conservative trope. Prudes claimed that slasher films were smut, little better than pornography. Ti West seems to agree, except he’s being complimentary. In its quieter moments, X makes a pat case for sexual liberation and draws the same equivalency between pornos and horror flicks. After all, filmmakers of some renown like Craven, Ferrera, and D’Amato all made adult films before becoming bona fide artists. And still others—Carpenter, Raimi—started out in low budget horror believing that their circumstances did not preclude them from making great art. Our intrepid filmmaker’s porno-within-a-film is certainly not great art, but West has an obvious affection for the whatever-it-takes attitude even as he strikes an exquisite balance between “elevated porno” and plain old sex appeal in his own film.

Old Howard gets the same matters all crossed in his mind too; discovering that his lodgers are making a dirty picture in the barn is both aggravating and exciting. What they’re doing is obscene, but also titillating. But he’s got the bum ticker and the wet noodle. Incredibly, the spirited effort to get Pearl into bed with Maxine gives the geezer a renewed sexual vigor that climaxes just as the film itself is cresting its zenith. This produces a weird sympathy that’s all tangled up with watching old people have sex; fairly tame sex, mind you, just as the whole film is mildly tame in the grand scheme of horror cinema, but old people sex! It’s not unlike the wary sympathy we feel for Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

If we peel back a layer or two and isolate the finale, stripping it of its in-the-moment intensity, we can see why West cast Goth in both roles (besides that they filmed the prequel back-to-back) and why we feel so strangely involved with these characters: Maxine is not only scared of Pearl raping her or blowing her head of with a shotgun, she’s also scared that she’s going to a follow a rut all her long life and end up in the same resentful spot where Pearl is now. She sees herself in Pearl, just as Pearl saw herself in Maxine when she spied on her porn shoot in the barn. One could easily read some comment on the male gaze into this dynamic, a notion skewered later when R.J. scoffs at the idea that his girlfriend (Ortega) might want to act in the film.

With all that hidden thematic baggage, the villains are thus far from the scariest you’ll find in a slasher, but X isn’t trying to be the scariest movie since sliced bread. It’s hard not to be impressed by how it all comes together, all these little subversive experiments successfully carried out under our noses while we enjoy the comfort food of an eminently satisfying slasher.