“All this happened, more or less.”

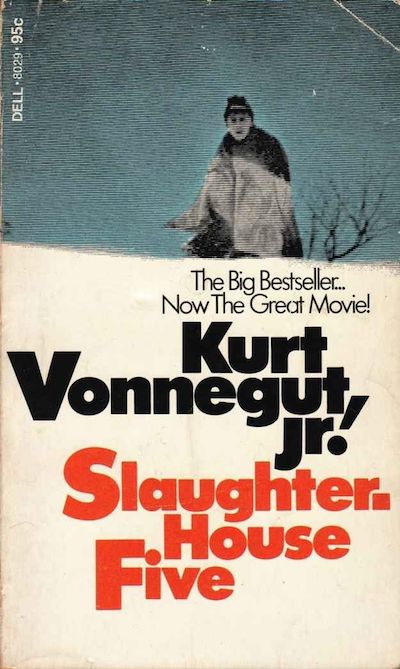

Inspired by the author’s own experiences in WWII and the bombing of Dresden, the nearly structureless Slaughterhouse-Five is a perfect introduction to the wonderfully zany mind of Kurt Vonnegut. His most popular work, it was released during the height of the Vietnam War. The book has perhaps been pigeonholed too neatly, nestling into the satirical war genre next to books like Catch-22, and the anti-war category alongside things like All Quiet on the Western Front and For Whom the Bell Tolls, when in fact it ventures well outside the boundaries of either of those classifications. It’s a fatalistic meditation on death, a goofy sci-fi romp, a scattershot collection of flavorful vignettes, and a creative exercise in the repetition of phrases and thematic elements. Vonnegut utilizes a unique style, stopping and starting the disjointed narrative every page or so, leading to a mesmerizing and eminently readable work that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Vonnegut begins the story with a first person prologue, and, as the narrator, he appears as a minor character throughout the story, crossing paths occasionally with the everyman main character Billy Pilgrim. Billy’s unique quality that sets the stage for the non-chronological telling of the story is that he is “unstuck in time,” meaning he lives his life out of order and in short snippets. Further, he relives these episodes ad infinitum. Initially Billy’s condition may seem like a quaint little wrinkle in a silly story, but when he is abducted by an alien race called Tralfamadorians (first appearing in Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan a decade prior), they explain to him that all moments exist eternally and that there is no free will that could allow for them to be changed. So, for example, they are kidnapping him not because they truly desire to, but because the moment of his kidnapping already exists; it always has existed and always will exist. What’s clever is that Vonnegut leaves room for Billy’s condition to be explained away by madness, which is what the characters around him choose to do.

Whether or not Billy’s condition is real is irrelevant to the aims of the book, though. From Billy’s point of view, he is jumping around in time. He was kidnapped by aliens and put on display in a zoo with a glass dome to protect him from the poisonous atmosphere along with a former adult film actress who was likewise abducted. They fall in love and have a baby, just like he does with his candy bar munching wife in the “normal” timeline. His wife bears him a son and a daughter. The son grows up to become a Green Beret. At any time, Billy can turn a door handle or nod off to sleep and find himself in another time, or he can jump-cut fifteen minutes into the future. It’s seemingly random. But since he has been taught that every moment is predetermined, he does nothing to change these moments. He merely relives them again and again.

The real joy in reading Slaughterhouse-Five is in the breakneck pace and the flavorful episodes that color the life of Billy Pilgrim. In ever-expanding circles, we witness his childhood, his time in the military, his career as an optometrist, his mental break, his old age, his time spent on Tralfamadore, and his death (which is characterized by violet light and a hum). Vonnegut’s writing is very simple, and is noteworthy for its black humor and repetition of phrases. The most common phrase, “So it goes,” is used to speak about death and mortality, to transition between subjects and timelines, and to curtail digressions into unexplainable things. It is probably used over a hundred times. There are a plethora of other phrases that Vonnegut employs that, along with the cyclical narrative, serve to give the novel a certain cohesion as well as to paint Billy Pilgrim as a simple man with matter-of-fact thoughts. In addition, since the reader picks up on the repetition and begins to read them humorously, certain morbid episodes can become digestible, for instance:

Only the candles and the soap were of German origin. They had a ghostly, opalescent similarity. The British had no way of knowing it, but the candles and the soap were made from the fat of rendered Jews and Gypsies and fairies and communists, and other enemies of the State. So it goes.

Several of the memorable events that are revisited from different angles: Billy is the sole survivor of a plane crash in Vermont; a high school teacher who volunteered to fight in WWII is executed for stealing a teapot from the wreckage of Dresden; Billy dreams up his own epitaph (a Vonnegut illustration is actually in the book) which reads: “Everything was beautiful, and nothing hurt”; Billy meets a man who has sworn revenge against Billy for the death of another man, although Billy is not responsible for his death at all (he is told not to worry, the revenge may not come for another twenty years). Further pushing the repetition, some phrases, such as “blue and ivory feet” or “mustard gas and roses” are used to describe different things in different timelines.

Kilgore Trout, a name more famous than those of many real authors, is a partial surrogate for the author who appears in many of his works, including Breakfast of Champions, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Jailbird, and Timequake. In Slaughterhouse-Five Billy Pilgrim becomes acquainted with the unknown writer of sci-fi when he befriends his roommate at the hospital, who happens to have boxes of the prolific author’s work under his bed. Billy becomes a huge fan, and eventually meets the author by chance, helping him deliver newspapers (his main source of income, since makes no many from his books). Billy invites him to his anniversary party. Vonnegut describes several of Trout’s fictional books, including one about the death of Christ, where a time-traveler takes a stethoscope back with him in order to determine if Jesus really died. “The time-traveler was the first one up the ladder… and he leaned close to Jesus so people couldn’t see him use the stethoscope, and he listened. There wasn’t a sound inside the emaciated chest cavity. The Son of God was as dead as a doornail. So it goes.”

The scattered nature of the story is a large part of its charm. It’s disjointed, jumping between time periods on a whim, almost too happy to change its train of thought on a dime, but somehow it all works as a whole. The jagged mosaic in its fullness is absolutely brilliant. Its anti-war message, while veiled somewhat behind the haze of humor and science fiction, is unfortunately perpetually relevant, and continues to resonate. (The book was originally subtitled “The Children’s Crusade” based on the fact that so many soldiers are asked to die for their country before they’ve even become adults.) The book is an enduring American classic and one that mostly everyone should read at least once. If you hate it, that’s fine; it’s pretty short. If you like it, Vonnegut has plenty of other good stuff.